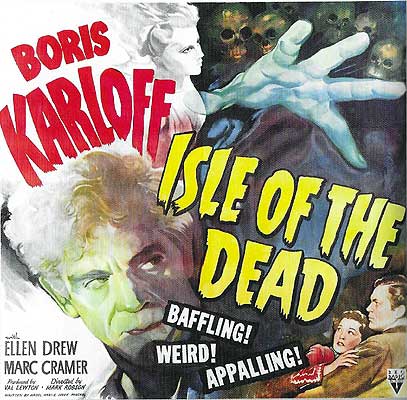

Isle of the Dead (1945) *

Isle of the Dead (1945) *

RKO’s Isle of the Dead is a remarkable little flick that comes very close to achieving what sometimes seems to have been the 1940’s horror movie ideal-- the creation of a film in which absolutely nothing ever happens. To me, it is one of the great mysteries of American pop culture that my grandfather’s generation could actually find something to be frightened of in movies like this one. Stagebound? Oh hell yes! Isle of the Dead takes place in exactly five rooms, one tent, and three “exterior” settings, all of which were quite obviously built on a soundstage. Talky? Hell yes, squared! There are all of three scenes that might loosely be described as “action” sequences, and one of them happens offscreen! Suspenseful? Hardly. If you’re smarter than your dog, you’ll see everything that doesn’t happen coming a mile away. But at least the acting’s good, right? I mean, these old films always have good actors, don’t they? Well, there are one or two in here, but everybody’s dialogue is stupid, and top-billed Boris Karloff has his not inconsiderable talents wasted by a role that requires him to completely break character without warning some two thirds of the way through the film.

At least the timeframe in which the movie is set is interesting. The year is 1912, the place is the Greek countryside, and the First Balkan War (in which Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria tag-teamed the Ottoman Empire in a three-fold war of nationalist self-aggrandizement) is raging. Karloff plays General Phyrides, commander of at least a corps of the Greek army. Phyrides is nicknamed “the Watchdog” for his aggressiveness and inflexible vigilance in defense of his nationalist ideals, and when we first meet him, he is in the process of ordering the execution of one of his colonels for reasons that are, at best, difficult to understand. (Phyrides essentially orders the colonel to shoot himself; this is that offscreen “action” sequence I mentioned.) Also present at the execution is Oliver Davis (Marc Cramer), war correspondent for the Boston Globe, who rags on Phyrides for a while about his draconian command techniques before going with him to an island cemetery to visit the grave of the general’s wife. (It makes a little more sense in the movie, but not much.) On the way, they encounter a field medic whose sole purpose in the movie is to inform them (and the audience) that Phyrides’s forces are suffering from an outbreak of the septicemic plague, an especially nasty disease that results when the bubonic plague bacillus attacks the bloodstream rather than its usual target, the lymphatic system. We never see this doctor again, so we know that this little stretch of dialogue has to be important.

And so it is, though it will be a while before we see how. Phyrides and Davis find Mrs. Phyrides’s coffin smashed and empty, leading them to seek out the home of the island’s sole apparent resident, a Swiss archaeologist named Albrecht (Jason Robards Sr., from Zombies on Broadway and Bedlam-- not the famous one, but his dad). The archaeologist explains that the grave-robbery occurred fifteen years ago, and was the work of some local villagers who were trying to raise money by finding antiquities to sell him. The bodies in the violated graves were all burned out of some superstitious fear. Albrecht has quite a crowd gathered at his house that night, as it happens; in addition to himself and Madam Kira (the place’s original owner, played by Helen Thimig), there is an English couple called the St. Aubyns, their Greek servant Thea (The Monster and the Girl’s Ellen Drew), and an alcoholic Cockney tin merchant by the name of Andrew Robbins (Skelton Knaggs, from The Ghost Ship and House of Dracula). The four guests are refugees who fled to the island to escape Phyrides’s war, and Thea in particular is none too pleased to see the general show up on the doorstep. Actually, the whole situation is a pretty bad gig for Thea. Her boss, Mrs. St. Aubyn (Katherine Emery, of The Maze), is cataleptic (she periodically lapses into a state of death-like shock) and is obviously getting sicker, and the fact that Thea herself remains healthy has convinced the highly superstitious Madam Kira that the girl is a vorvolaka, a sort of vampire-werewolf thing (also known by the names vrkolak, vrkolaka, and vrykolakas, depending on where in Greece you go).

As if all that weren’t bad enough, the next morning, Robbins is found dead in his room of septicemic plague. (I told you it was important!) An army physician called Dr. Drasos (Ernst Deutsch, from The Golem) comes to investigate, and places the island under quarantine until such time as the Sirocco-- the hot, dry wind current from the south-- comes and kills off the fleas that spread the plague. I’m sure you can imagine how Madam Kira interprets it when people start dropping dead of the plague, and how difficult that makes life for poor Thea. And I’m sure you can also imagine the potential for disaster that comes with putting a cataleptic in the same house as a woman who believes in vampires. What you’ll never see coming is the completely motiveless 180-degree shift in the personality of Phyrides from the ruthlessly rationalist materialist he is to begin with to the gibbering superstitious nutjob he becomes after Dr. Drasos dies of the plague. This transformation is a glaring example of not playing fair with the audience, and it’s quite clear from watching the movie that neither Karloff nor director Mark Robson could think of any way to make it seem believable. Equally startling is the complete indifference with which Isle of the Dead approaches its climax; it’s as though Robson was as bored with the film by that point as I was, and was unwilling to give it any more of his time or attention. There is absolutely no excuse for a scene in which people come out of graves to stab other people with tridents to be boring, but that’s exactly what the climax of this movie is. Even the actors, even the ones whose characters are getting stabbed, seem to be bored.

And then there’s a nice little factual error to consider. Not bad science this time-- the movie actually does a pretty good job with the septicemic plague. No, with Isle of the Dead, we’re looking at bad history. During the first half of the film, this movie approaches the ancient pagan religion of the Greeks as if it were still being practiced out in the sticks, or at least as if it were only very recently extinct. The fact that the treatment of the subject changes radically later (at about the same time that Phyrides’s personality does) makes it seem as though somebody finally came up to the filmmakers at that point and told them that Greece had been Christian for about 1450 years by the time in which Isle of the Dead takes place! Now, ordinarily, such an amazing screw-up would be funny, but for some reason, it isn’t here. Instead, it just further undermines the air of professionalism that Karloff tries so futilely to project around the movie. El Santo’s final verdict: Feh!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact