The Maze (1953) ***

The Maze (1953) ***

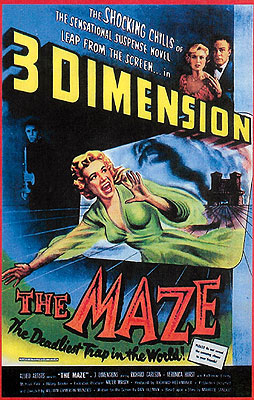

Now weíre getting back into more familiar territory. The Maze still fits within the historical parameters of gothic romance, but itís also much more of a gothic horror film than anything else Iím looking at for the B-Mastersí Bad Place roundtable. And if you think for a minute about what else was playing on American theater screens in 1953, youíll understand that that alone is enough to make it an extremely peculiar movie. The makers of The Maze werenít content to be weird in just one way, however. The Maze is equally anachronistic for all the German Expressionist atmospherics slathered over it by director and production designer William Cameron Menzies, at a time when the typical Hollywood B-picture was built to look like a training film for the Army Corps of Engineers. Itís unusual for bringing the horror and romance aspects of gothic fiction back together under the same roof, as if none of the genre developments of the past 150 years had ever happenedó and it canít claim antiquity of source material as an explanation, because Maurice Sandozís novel of the same name was published as recently as 1945! Most of all, The Maze confounds audience expectations by haunting its sinister Scottish castle not with a ghost, but with something fit to be portrayed by that ultimate standby of 1950ís special effects technology, a man in a rubber suit. It even goes so far as to justify the monsterís existence with screwball pseudoscience. Iím surprised The Maze doesnít have more of a cult following, because there really was nothing else like it in 1953, and thereís precious little else like it even today.

We begin at the aforementioned sinister Scottish castleóCraven Castle by nameó where servants William (Michael Pate, from The Strange Door and Curse of the Undead), Robert (World Without Endís Stanley Fraser), and Simon (Owen McGiveny) have trouble on their hands. It seems their master, Sir Samuel MacTeam, has died, and from the conspicuously big deal Menzies makes of not showing us the body, I suspect he did not go peacefully in his sleep. The men are also concerned over the whereabouts of somebody else, someone whose very name they seem loath to utter. Nevertheless, itís clear that all concerned knew this situation had to arrive sooner or later, and have been planning accordingly. William gives the order to put those plans into action now.

Then The Maze takes a sharp left turn into Rebecca territory, as the almost painfully proper Mrs. Edith Murray (Isle of the Deadís Katherine Emery) breaks in to narrate that that was how it all began. She goes on to drop a ton of ominous foreshadowing on us before permitting the movie to resume in Cannes, France. I guess all the hotels in Monte Carlo were booked up, huh?

Edith is there, of course, together with her niece, Kitty (Peeping Tomís Veronica Hurst), Kittyís fiancť, Gerald MacTeam (Richard Carlson, of The Amazing Mr. X and The Ghost Breakers), and a friend of the young folks named Richard Roblar (Robin Hughes, from The Thing that Couldnít Die and The Son of Dr. Jekyll). Itís a hell of a marriage Kitty has lined up for her, because however lumpishly American Gerald might seem, he belongs to the Craven line of Scottish baronets. Indeed, he lived for a while at Craven Castle as a boy, although he hasnít seen it or his Uncle Samuel in fifteen years. It therefore comes as quite a surprise to all concerned when Gerald receives an urgent letter from the castle summoning him there to conduct some hush-hush business related to his status as sole heir to the estate. Gerald and Kitty are due to marry in just a few days, but heís confident that he can get everything sorted out in time for their wedding to proceed on schedule.

Yeahó not quite. Two whole weeks go by before Kitty and Edith receive any news of Gerald, and even then it isnít news from him. The update comes in the form of a newspaper obituary for Geraldís uncle, implying that Kittyís fiancť has been incommunicado at least partly because heís been busy organizing a funeral fit for a baronet. (Itís also partly because thereís no telephone at Craven Castle, nor any other 20th-century conveniences, but the ladies already knew about that.) Less explicable is his continued silence even after Uncle Samuel is in the ground, despite several letters from Kitty. Finally, after a full two months, Edithó not Kittyó gets a letter from Gerald releasing the girl from their engagement, and yet simultaneously pledging his eternal love and fidelity. Itís all very strange, and rather than accept that their relationship is over, Kitty determines to visit Craven Castle and make Gerald explain himself.

The castle and its grounds make quite an impression. Located in the middle of nowhere, Craven Castle is accessible only via a long cab ride from a driver who would visibly rather go anywhere else. As advertised, it is without phone service, electricity, gas heat, and probably even plumbing. Thatís not the weird part, though. The windows in all the guest rooms are walled up, the floors in most areas are covered with rubber mats instead of conventional rugs or carpeting, and the staircases are of extremely peculiar design, more a series of landings than stairs in the ordinary sense; climbing or descending them is both awkward and tiring. The grounds are dominated by a spooky old hedge maze, made even spookier by the perpetually locked doors at all the entrances. And speaking of locks, Kitty and Edith will soon discover that the Craven clanís idea of hospitality includes locking any and all guests into their rooms overnight. Now thatís weird. William and Robert are brusque and unwelcoming to the point of rudeness during the day, too, as if the physical environment werenít already sufficiently off-putting. But the most striking thing to confront Kitty and her mother at Craven Castle is the change thatís come over Gerald. Heís become callous, hard, angryó arguably even cruel. More alarming still, the eight weeks heís spent at his ancestral manor have aged him a decade or more. Obviously something very bad is going on at Castle Craven, and Kitty is determined to get to the bottom of it.

The very remoteness of the estate is enough to give the women an excuse to spend the night there despite their hostís seemingly unreasonable objections, and the cold that Edith wakes up with thanks to the chill and damp provides an alibi for an indefinite stay (albeit obviously a relatively short one). During that first night and the morning thereafter, Kitty makes further unsettling discoveries. Thereís a secret door in her room, for one thing, giving access to a whole network of hidden passageways; one of the latter leads to a window high up in the house, from which most of the topiary maze can be seen. And although itís too dark to tell what, exactly, Kitty is sure that she detects activity of some kind down in the maze when she looks out on it. Something moves around by night inside the castle, tooó something that advances with a sort of slithery hop. Kitty hears the thing pass right by her bedroom door before she goes snooping about among the secret corridors, and she finds a trail of muddy, webbed footprints on the rubber-clad hallway floor in the morning. All thatís pretty creepy, but sheíd be even more unnerved if she overheard a hushed conversation between Gerald and William. Evidently there used to be a maid at Craven Castle, but she was attacked a few days before the Murraysí arrival, when she defied orders and went poking around in the maze. William just got word from the village that the woman has died of her injuries, and Gerald mandates that the butler is to hire only men to replace her if he and Robert are unable to handle her former duties themselves.

The mysteries surrounding the castle are surely important, but what worries Kitty first and foremost is Geraldís health, both physical and mental. Knowing, however, that he would never consent to a formal examination, she concocts a cunning subterfuge. Kitty correctly perceives that Simon the groundskeeper is less invested in the Craven Castle Conspiracy than the other two servants, so she passes him a letter to send along to Richard Roblar. In it, she urges Richard to come out at once with their mutual friend, Dr. Bert Dilling (John Dodsworth, from Bwana Devil and The Magnetic Monster). Both men are to bring their significant others (Peggy Lord, of Lost Continent and Invaders from Mars, and Lilian Bond, from Man in the Attic and The Old Dark House), so that the visit can plausibly be passed off as an impromptu social call occasioned by a cross-country road trip. With any luck, Gerald will find himself just as powerless to turn his friends away as he has been to get rid of Kitty and Edith, and Dr. Dilling will be able to observe his behavior closely enough to make some educated guesses, if not a proper diagnosis. This is the point at which Kitty would really have benefitted from knowing about the cleaning lady. By bringing enough of her friends to Craven Castle to outnumber Gerald and his staff, she has unwittingly overwhelmed the system whereby Geraldís ancestors for the past 200 years have tried to minimize the danger posed by a very peculiar family curse.

Devotees of H. P. Lovecraft take note: although it bears no direct connection to any of Lovecraftís work, The Maze is the earliest film I know of to deal with a complex of his favorite themes in a specifically Lovecraftian manner. You wonít find any of the cosmic stuff here, but the Attic Baby/Frog People/Devolving Inbred Aristocrats routine wouldnít get another workout like this onscreen until probably Dagon almost 50 years later. Lovecraft is just about the last author I would normally associate with the gothic tradition, so itís neat to see his style merged with it so seamlessly. Indeed, once you see how the pairing is handled here, youíll wonder why it hasnít cropped up more often. What might be even more surprising, though, is how earnestly effective The Mazeís Lovecraftian elements are, even despite the patent silliness of a human birth defect somehow producing a giant, immortal, intelligent frog. William Cameron Menzies plays completely fair with the creature, too. He keeps it scrupulously offscreen throughout most of the film in that characteristic 50ís way, but gives us as clear a look at it as we could ask for when it really counts. The amphibian man is disturbingly lifelike, not least because special effects maestro Augie Lohman remembered that frogs are proportioned differently from humans, and designed the suit accordingly. Only if youíre consciously looking for them do the body contours of the man inside it become sufficiently evident to spoil the illusion.

On the gothic front, the lionís share of the credit for The Mazeís success clearly belongs to Menzies and cinematographer Harry Neumann. Rarely have I seen a prevailing stylistic trend bucked so forcefully. On the usual Allied Artists pittance, Menzies and Neumann managed to create an emotionally convincing (if not necessarily plausible) Old World castle, largely just by knowing where to point the lights. All those dense pools of shadow are rendered even more effective by the proportions of the interior sets, in which the ceilings are always a little too high and the walls are always a little too close together. That distortion of the shooting environment comes across even more strongly thanks to the filmís 1.33:1 aspect ratio. Granted, the old-fashioned framing was probably chosen on budgetary grounds, but it was a smart move just the same. (Besides, The Maze was originally shown in 3-D, so it had its gimmick bases covered.) Finally it would be remiss of me not to say something about the hedge maze itself, both the miniature set used to represent it as seen from the castle windows and the full-size version where much of the climax takes place. Modern viewers will most likely be put in mind of the similar maze at The Shiningís Overlook Hotel, but remarkably enough, The Maze can withstand the comparison. Itís a spooky, evocative setting, practically dripping with latent menace.

Where The Maze falls somewhat flat is in the human element. Commendably, that doesnít include Kitty, Edith, or the actresses portraying them. They come across as tough, courageous, clever, and most of all sensible, suffering from barely any of the ills to which B-movie heroines were prey in 1953. No, here itís the men who disappoint, stumbling stiffly about in roles for which they have little or no affinity. I wish I could say it was a revelation to see Richard Carlson play a morally compromised, hag-ridden antihero after all those interchangeable square-jawed scientist types, but the performance never really comes together. To start with, Carlson is the least convincing Celtic laird since Lon Chaney Jr., but more importantly, he doesnít seem to have fully grasped the genre expectations inherent in the part. Perhaps he should have pulled a few credit-hours of coursework amid the books on Mrs. Carlsonís nightstand. (Carlson would come closer to the mark he misses here in Tormented at the end of the decade. That movie isnít the slightest bit gothic, but it does cast him as a romantic lead whoís a bit of a bastard.) Neither Michael Pate nor Stanley Fraser is up to the challenge of playing a male Mrs. Danvers. In their hands, William and Robert seem less implacable masters of topping from below than just a couple of highfalutin assholes. And the less sad about the crowd playing Kittyís friends, the better. Fortunately, Menzies understood what he had in Veronica Hurst and Katherine Emery, and got out of their way while they walked off with the picture.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable on haunted, cursed, possessed, or otherwise evil locations. Click the link below to tour the rest of this neighborhood of the damned.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact