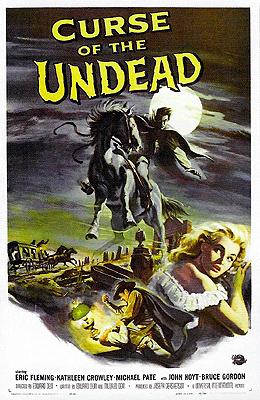

Curse of the Undead/Mark of the West (1959) ***½

Curse of the Undead/Mark of the West (1959) ***½

Now that we’ve seen what can go wrong when a filmmaker gets it into his head to play cowboys and vampires, let’s see what the same basic idea looks like when it’s done right. Curse of the Undead/Mark of the West is about as anomalous a movie as you could ask for— an old-school Gothic horror film with a Western setting, made in a year more commonly associated with rampaging aliens, insane scientists, and radioactive dinosaurs. More surprising still, it is clearly the result of a well thought-out effort to combine elements from two not-obviously-compatible genres in a way that both makes good sense and comes across as more than just a ticket-selling gimmick.

The opening scene would be fairly conventional if it weren’t for all the Wild West paraphernalia on display. Town doctor John Carter (John Hoyt, from The Time Travelers and When Worlds Collide), preacher Dan Young (Eric Fleming, of Fright and Queen of Outer Space), and a couple of concerned-looking women are gathered around the bed of an ailing teenage girl. Evidently the girl’s present condition is an improvement over the past couple of nights, but you couldn’t prove it by me. While Young and Carter talk, it comes out that the girl in the bed isn’t the only one the doctor has seen lately with her strange, wasting illness. Carter has never seen or heard of any disease quite like it, and considering his utter and miserable failure to save the last three girls he has attempted to treat for it, he’s inclined to give Dan’s prayers more credit for the patient’s turnaround than his own medicine. Just barely are these last words uttered— in conversation out in the parlor onto which the patient’s bedroom door opens— when both men discover they have spoken too soon. The girl screams suddenly, and when the other occupants of the house come rushing to her room, they find her stiff and dead, her upper body hanging over the side of the bed. And though none of the characters yet appreciates their full importance, we in the audience know exactly what’s going on when Dan finds a pair of small puncture wounds on the side of the girl’s neck, oozing small trickles of blood.

When Dr. Carter returns to his home, we learn that the man has equally weighty problems of a more mundane nature than a vampire on the prowl. Carter is also a rancher, and it is his misfortune that his grazing range borders that of Buffer (Bruce Gordon, from Piranha and Timerider), the unscrupulous land-grabber without whom the cast of no Western can be complete. Buffer’s latest shenanigans involve damming up the stream that waters both his land and Carter’s— ostensibly to create a drinking pond for his own cattle, but really to dry out Carter’s rangeland and turn it into a big enough economic liability that he’ll have to sell it. That Buffer is the only other man in the area with the money to buy that big a parcel of land is— clearly— just a fortuitous coincidence. Well as it happens, Carter’s son, Tim (Jimmy Murphy), caught Buffer’s men erecting the dam, but when he came down on them, all he got for his trouble was a complimentary ticket home on the Bitchslap Coach Service. Doc Carter hears the main story from Tim, with supplemental details filled in by his daughter, Dolores (Kathleen Crowley, of Target Earth and The Flame Barrier). Tim, naturally, is all fired up to go back to Buffer’s place and start shooting, but Carter talks him down and then heads into town to see first the sheriff (Ed Binns) and then Buffer himself. The doctor comes home dead from this errand— not because of anything Buffer does, but because he runs afoul of a black-clad cowboy on the way home. We know the dark rider means trouble even before he does anything; not only is he riding around alone in the dead of night, his appearance is also accompanied by eerie 50’s Theremin music.

Now hopefully you’re smart enough that I don’t need to tell you how Tim and Dolores are going to take it when their father’s carriage brings home a bloody corpse. Tim, being the more hotheaded of the two Carter kids, straps on his guns as soon as his father is in his crypt (note, by the way, that the dark rider shows up after the funeral and climbs into Dr. Carter’s coffin), and sets off for the saloon that is Buffer’s favorite hangout, in direct defiance of Dan Young’s warnings against this rash course of action. (In case you’re wondering why Dan spends so much time hanging out at the Carter place, it’s because he and Dolores have a thing for each other, a point which the movie won’t get around to making for another fifteen or twenty minutes.) Once there, Tim downs most of a bottle of some hideous-looking, thick, black liquor (What is that shit? Jägermeister?) while waiting for Buffer to show up. The sheriff gets to the saloon first, and he does his best to get the boy packed off for home. When that fails, he remains at the saloon so as to act as the voice of reason when Buffer makes his inevitable entrance. It almost works, too, but Tim eventually gets Buffer so riled up with his jeers and threats that a gunfight breaks out after all, and the older, more experienced— and let’s not forget sober— Buffer emerges victorious.

The day after Tim’s funeral finds Dolores hanging up posters all over town offering “$100 for the Death of a Murderer.” Buffer, who knows the poster refers to him, doesn’t think anything of it until a stranger who calls himself Drake Robey (Michael Pate, from Black Castle and The Howling III: The Marsupials) comes into the saloon carrying one of the posters. Yup. It’s the dark rider, alright. Under ordinary circumstances, Buffer would count himself lucky that his men catch on pretty quick, but when one of them draws down on Robey, he gets the Peacemaker blasted clean out of his hand, even though he fires the first shot. The unscathed Robey saunters on out of the saloon toward the Carter place, telling Buffer they’ll surely be seeing each other later. The thing is, though, that Buffer’s lackey is dead certain his shot hit the other man square in the chest.

Meanwhile, back at the Carter ranch, Dan is doing his damnedest to convince Dolores that hiring a hitman is not the way to deal with Buffer. He has made precisely zero headway when Robey shows up to talk business with the aggrieved girl, and knowing when he isn’t wanted, Dan gets back to work on a project that has kept him very busy since the death of his old friend: going through Dr. Carter’s papers and effects, trying to find a will. Two very important things happen that night, both of them involving Drake Robey in some way. First, the hired gun, whom Dolores has put up in a spare room at the ranch house, sneaks into his hostess’s bedroom after she has gone to sleep, and bites her on the neck. Then, back at his place, Dan Young makes a discovery that explains the whole situation. There is a hidden compartment in Dr. Carter’s strongbox, and it contains an old map of the Carter property from Spanish colonial days, along with the diary of Don Robles, the property’s original owner. The diary tells how the don’s elder son, Drago, murdered his younger brother after coming home from a long trip abroad to find him dallying with Drago’s wife. Drago was not a cruel or vindictive man by nature, however, and over the ensuing months, he became increasingly consumed by grief and remorse, until eventually he stabbed himself to death in his brother’s tomb. Immediately after Drago’s suicide, young women throughout the neighborhood began contracting a mysterious wasting disease; even Drago’s wife came down with it. Then one night, Don Robles entered his daughter-in-law’s room in response to what sounded like the woman’s screams, and found a black-clad man standing over her bed. Robles fought with the intruder, and when he finally got a look at the man’s face in the moonlight, he was horrified to discover that it was Drago, who had been buried only three days before. Realizing his son had become a vampire as a result of his suicide, Robles tried to destroy him in his crypt the next day, but he chose the wrong bit of folklore to supply his anti-vampire measures, and succeeded only in driving the monster into hiding. So does anybody else notice the strong phonetic similarities between the names Drago Robles and Drake Robey?

We’re back in familiar Gothic territory now. Dan tries fruitlessly to convince Dolores of the danger she has placed herself in by bringing Robey into her home, accomplishing nothing beyond estranging her from him, and driving her further into the arms of the vampire. Robey falls in love with Dolores, but because the vampire mythos employed by this movie does not provide for the undead to propagate themselves by turning their victims into vampires, he is forced into an unexpected internal struggle between his love for the girl and his biological imperatives. Dolores, weakened by the nocturnal visits from Robey that she has already endured, begins wasting away; we know she’s headed downhill fast when she acquiesces meekly to Dan’s renewed efforts to make her rescind Robey’s contract with her on Buffer’s life. There’s nothing familiarly Gothic about the ending, though, which presents us with a vampire-killing strategy that is both completely unique in the annals of film and brilliantly appropriate given the movie’s distinctive spin on the vampire subgenre.

The best thing about Curse of the Undead is that it refuses equally to be bound by the cliches of either the Western or the vampire movie, and instead combines the elements it uses of each into a logically consistent whole. The standard range-war plot, for example, is subverted here by making the bad rancher unscrupulously self-interested, as opposed to reflexively evil. Buffer may be an asshole, but he’s wary of provoking the sheriff and smart enough to know when he’s been beaten; rather than sending a posse of useless underlings after Robey, he recognizes that he’s outmatched, and submits instead to an onerous private settlement with Dolores, brokered by Dan Young. Furthermore, the West of Curse of the Undead is significantly less Wild than one generally expects of Hollywood. Sure, everybody goes around armed just about all the time, but only Tim— at least nominally one of the good guys— has the shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later attitude typical of a movie cowboy. Buffer does his damnedest to swallow his pride and walk out of the saloon when Tim picks his fight with him, and only draws his gun when it becomes obvious that the armed-and-hammered boy isn’t going to listen to the sheriff and back down. The sheriff, meanwhile, obviously prefers to do his job with reason and remonstrance, rather than with fists and firearms, and is thus far removed from the stereotype of the gunslinging, tough-guy lawman. And in Dan Young, we are treated to the startling spectacle of a pistol-packing preacher, a sort of Wild West equivalent to the Shaolin monks of 70’s kung fu films.

Then, looking at the movie from the horror perspective, we are faced with Drake Robey/Drago Robles, a vampire unlike any a 1959 audience would have seen before. To start with, I love the conceit of the vampire gunslinger. It’s perfect— what better line of work could there be for a man immune to bullets in a setting where law and order are still ultimately dependent upon armed violence? Second (and coming from Universal, this is nothing short of astonishing), Robey’s vampirism is that of Spanish folklore, rather than that of Victorian literature. Contrary to the impression you might get if your knowledge of vampirism comes solely from movies with the name “Dracula” in the title, there is a huge and varied universe of vampire legendry, and in no two cultures is the vampire quite the same creature. Mega-Catholic Spain, naturally, sees its vampires through a thick prism of Christianity; religiously themed countermeasures are reckoned far more effective than those smacking of pre-Christian folk magic, and the Spanish version of vampirism works less like a supernatural contagion than as an earthly consequence of mortal sin. Drago Robles becomes a vampire because he commits suicide, which in Catholic terms is about as grave a sin as there is— after all, the suicide, by ending his life, treats an irreplaceable gift from God with contempt. I therefore find it especially fascinating that Robey’s character should exhibit a combination of personal decency and moral powerlessness that mirrors the odd lack of congruence between sin and substantive evil that is, from my unbeliever’s perspective, the most striking feature of Roman Catholic dogma. Drago Robles was a fundamentally good man who let his passions get the better of him on two disastrous occasions, the second of which cost him his soul. Even now that he is a vampire, it is still possible to see in him the good man he once was, but because of two glaring moral fuck-ups, he is now forced to do evil against his will for all eternity. It’s a thoroughly medieval notion of divine justice, but because it is one that is still held to a great extent by the Catholic Church— and was still wholeheartedly subscribed to by the Church in Spain at the time when Curse of the Undead is set— it makes perfect sense that it should inform this movie’s vampire mythos, to the exclusion of the more familiar notions handed down to us by Stoker, Polidori, and whoever the hell it was that wrote Varney the Vampyre. It also makes Curse of the Undead as convention-defying a horror film as it is a Western, and compelling viewing from either angle.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact