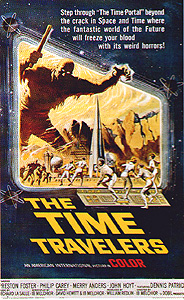

The Time Travelers / Time Trap / This Time Tomorrow / Depths of the Unknown (1964) ***

The Time Travelers / Time Trap / This Time Tomorrow / Depths of the Unknown (1964) ***

Go into just about any gathering of human beings in the world and namedrop Ib Melchior, and the odds are that you will be confronted with an entire roomful of blank stares. This is a damn shame, despite the fact that he was the guy Warner Brothers originally wanted to preside over the hatchet-job that would have turned Gojira no Gyakushu into The Volcano Monsters. Melchior was one half of the creative team behind the amazing The Angry Red Planet. He gave us Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Irwin Allen stole the idea for “Lost in Space” from Melchior’s unfilmed screenplay, Space Family Robinson. In other words, Ib Melchior is responsible, directly or indirectly, for some of the most demented science fiction since Phil Tucker called it a day in response to the critical and box-office smackdown he received for Robot Monster and The Cape Canaveral Monsters. The Time Travelers/Time Trap/etc., Mechior’s answer to The Time Machine, is, surprisingly enough, a far more serious film than one usually expects from him, but is, in its way, just as far off-kilter as its more obviously daffy cousins.

The opening scene offers up some of the most ridiculous pseudo-scientific technobabble on record. The occasion is the first full-scale test of a machine capable of looking through time, a sort of trans-temporal television set. The scientist in charge is Dr. Eric von Steiner (Preston Foster, of Doctor X); his colleagues are Dr. Steve Connors (Monster’s Philip Carey) and a grad student named Carol White (Merry Anders, from Women of the Prehistoric Planet and House of the Damned). As the experiment begins, a lab technician in blue coveralls comes in and starts hitting on Carol. This is Danny McKee (Steve Franken, who mostly worked in the made-for-TV field— look for him in Ants! and Terror Out of the Sky), and the combination of his coveralls, his voice, and the “Mc” at the front of his name should tell you that we’re going to spend much of the movie’s running time wishing for his death, for Danny McKee is (cue the appropriate music from the Creature from the Black Lagoon score) the comic relief! Carol blows off Danny’s advances, and gets to work. The experiment isn’t going terribly well, apparently because von Steiner’s machinery is having trouble channeling the necessary power levels. Dr. Connors impetuously cranks up the power as high as it will go, with results both good and bad. On the good side, the machine’s viewscreen fills with the image of the land outside the lab as it will appear a century into the future. On the bad side, the power overload cooks the inner workings of the device, giving rise to the usual shower of sparks and cloud of billowing smoke.

But oddly enough, the screen doesn’t go dark when this happens. Danny is the first to notice the anomaly, and he’s also the one who figures out the reason why: to the astonishment of all concerned, the electrical fire in the machine has fortuitously rearranged the connections among its circuits in such a way as to transform it from a trans-temporal TV into an honest-to-God time portal! This remarkable piece of serendipity comes to light when Danny tries to touch the screen, and sticks his hand through it instead. Overcome by excitement, McKee then steps completely through the portal, and goes running off. Von Steiner sees this, and being a rather more level-headed guy than the comic relief, begins worrying about what kind of trouble Danny might get himself into in the late 21st century. Leaving Connors and White to monitor the equipment and make sure the portal doesn’t collapse, von Steiner steps through to go looking for McKee. Connors follows when he sees a gang of dangerous-looking men armed with knives and clubs climbing over a ridge beyond the portal; he doesn’t think his older colleague will last long if that bunch catches up to him, and he wants to warn him and McKee of their peril. Finally, Carol abandons her post too, apparently because she’s a woman in a movie from the mid-1960’s.

The result of all this dereliction of duty is both dire and predictable. The time portal, with no one in the lab to look after it, closes, leaving von Steiner, Connors, White, and McKee stranded in what looks to be a post-nuclear apocalypse future. And before long, those men with clubs (who, now that we get a good look at them, appear to be post-nuclear apocalypse mutants) spot the unwitting time travelers, and start chasing after them. Von Steiner and company eventually duck into a cave for cover, and to their great surprise, an electric forcefield springs up over the cave’s mouth, denying the mutants entry! Moments later, a middle-aged woman in futuristic coveralls (Joan Woodbury, from King of the Zombies and The Living Ghost) appears at the other end of the cave, accompanied by a squad of curiously intimidating androids.

The woman introduces herself as Gadra, and takes the time travelers to meet the other leaders of her society. Chief among these is Dr. Varno (John Hoyt, from When Worlds Collide and Curse of the Undead), who explains that the world as our heroes knew it was destroyed early in the 21st century by nuclear war. The mutants who attacked the time travelers are all that is left of the human race on the planet’s surface. Fortunately, a group of concerned scientists had, by the time of the final war, established a sort of utopian community underground; I’m sure these folks were perceived as cranks and loonies at the time, but they got the last laugh, because their descendants are now the last living remnant of civilized humanity on Earth. The problem is that they will not be able to remain on Earth much longer. The contamination of the surface is slowly working its way down into the planet, food is becoming increasingly difficult to find up above, and the mutants have become increasingly hostile toward their civilized downstairs neighbors. With this in mind, Varno and his people have begun building a starship to take them to an Earth-like world in orbit around the star Alpha Centauri. The ship will be ready for liftoff in about a month, and if all goes according to plan, healthy human beings will able to walk in the sunlight (okay, fine— the Alpha Centauri-light) again.

What all this means for von Steiner and his colleagues is that they will not be able to return home. Von Steiner, Connors, and White think they could build themselves a new time machine, but their best guess is that it would take them three months to do so. Since they obviously couldn’t survive two months’ worth of mutant attacks without Varno’s people to look after them, such a project is clearly out of the question. So instead, Varno and Gadra invite the four temporal castaways to join them on their voyage into space, an invitation which is accepted without hesitation.

But Varno and Gadra aren’t the only members of the Council, and some of their fellows might see things a little differently. In particular, Councilman Willard (Dennis Patrick, from Dear Dead Delilah and House of Dark Shadows) is not at all happy with the idea of taking on four extra passengers. The design for the starship was mostly his, and thus he has a greater appreciation of the problems the additional human cargo presents. The ship’s design is very tight, and with construction so advanced, Willard doesn’t see any way to squeeze in the extra food, water, suspended animation pods, and android maintenance staff that von Steiner’s people will require. Willard voices his objections at the first Council meeting after his staff finishes crunching the numbers related to modifying the ship for four more people, and his resolution against bringing the time travelers along passes with only Varno and Gadra opposing. After breaking the bad news to their guests, the two Council-members pledge to do whatever they can to help them build a new time portal.

A handful of scenes later, the portal is just about ready, as is only to be expected in a film of this vintage. But then things go off the rails in a way more characteristic of the 1970’s. The mutants have figured out that the starship is nearly ready to launch, and that all the food, water, and supplies the troglodytes need for their journey to the stars will soon be loaded aboard, making the ship an extremely tempting target for brigandage. On the very day of the launch, the mutants lay siege to the underground city, throwing monkey wrenches into both Varno’s and von Steiner’s plans to escape from the poisoned Earth. The fate that befalls both groups would be amazing enough in any movie; keep in mind as you watch that this film was made in 1964, and you’re going to need goddamned scaffolding to keep your jaw off of the floor.

While it’s the ending that really sets The Time Travelers apart from the run of the 60’s sci-fi mill, it’s the tiny detail touches throughout that mark it as the work of Ib Melchior. The creepy, mouthless faces of the androids; the free love practiced by the cave-dwellers (years before the hippies popularized the concept, I might add); the surreal glimpses of night life and recreation in the scientists’ utopia; a cameo by Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forest J. Ackerman in a scene that exists for no reason other than to set up a bad visual pun— all these things are quintessential Melchior. Not only that, they’re almost enough to curb my resentment of the Danny McKee character, in that most of the really bizarre stuff happens in scenes devoted to the subplot concerning his budding romance with a young female cave-dweller named Reena (Delores Wells).

Finally, I’d like to draw your attention to a few points indicative of the unexpected impact this film had on its genre in the years following its release. First, 1967’s Journey to the Center of Time borrows shamelessly from this movie, duplicating its kicker ending almost exactly. In addition, Irwin Allen— the same guy who turned Melichior’s screenplay for Space Family Robinson into the TV show “Lost in Space” without giving Ib any credit whatsoever— later plagiarized this movie’s script into a story called “Time Tunnel,” which he filmed as the pilot for a TV series in 1975.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact