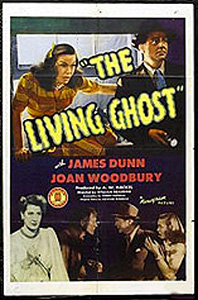

The Living Ghost/Lend Me Your Ear (1942) -**

The Living Ghost/Lend Me Your Ear (1942) -**

Ever wonder what one of Monogram’s idiotic wartime fright films would look like without Bela Lugosi, John Carradine, or even Mantan Moreland to give it marquee value? Well wonder no longer. The Living Ghost features absolutely nobody you’ve ever heard of except in the context of other Poverty Row productions or 1950’s TV guest spots. Like a lot of its studio’s early forays into the genre, The Living Ghost is really more a mystery with extra helpings of ghoulishness and spooky atmosphere than a horror movie in the strict sense, and its “ghost” is as much of a semantic cheat as the ones in The Invisible Ghost or Ghosts on the Loose. It may lack the utter irrationality of the Lugosi pictures made under Sam Katzman’s oversight, but with William Beaudine in the director’s chair, you can count on it exhibiting none of the conventionally recognized characteristics of quality filmmaking, either. In that sense if no other, The Living Ghost does not disappoint.

Millionaire Walter Craig (Gus Glassmire, from The Mad Ghoul and Captive Wild Woman) has gone missing. He was up and about when the rest of his family turned in for the night, but then gone without a trace the next morning. His bed had not been slept in, and there was no sign of a struggle anywhere in the Craig mansion (which, incidentally, is the same set as the Kessler mansion in The Invisible Ghost and the Saunders mansion in Black Dragons). The police haven’t made any headway in the case— and when we meet Lieutenant Peterson (Pillow of Death’s J. Farrell MacDonald) later, we will immediately understand why not— so the relatives are starting to think about hiring a private detective. Luckily, Craig’s lawyer, Ed Moline (Paul McVey, of Bwana Devil and Mystery of the 13th Guest), has a friend in the business… or sort of in the business, anyway. Nick Trayne (The Ghost and the Guest’s James Dunn) is officially retired, but he used to be the best detective the district attorney’s office had (wait a minute— the district attorney’s office?), and Moline is confident that he can coax Trayne into taking the case with a little help. The $25,000 that Craig’s wife, Helen (Edna Johnson), offers to pay for Trayne’s services most likely falls under the heading of a lot of help, and Moline heads off to see Trayne with Craig’s secretary, Billie Hilton (Joan Woodbury, from King of the Zombies and Phantom Killer), that afternoon.

Moline warns Billie that Trayne is a little eccentric, and he isn’t kidding. The ex-detective is now in business for himself as a “sympathetic ear,” which is apparently kind of like psychotherapy, except that Trayne doesn’t even pretend to solve his customers’ problems. He literally just listens to them unburden themselves for a fee of two dollars per hour, dressed up in a “comforting” swami costume. This does not strike Billie as an encouraging portent, but Moline assures her that men of Trayne’s genius often have a screw or two loose. He also advises Billie that the best strategy for winning Trayne over should he prove obstinate is to belittle his intelligence and professional acumen. Trayne never could stand to have his abilities called into question, and he’s practically guaranteed to sign on if challenged in that way. Trayne does indeed refuse to take the job when Moline lays it out for him, and Billie belittles like nobody’s business. The detective is in the car on his way to the Craig place within the hour.

The first thing Trayne does upon his arrival is to meet the family— which in a movie like this is the same thing as meeting the suspects. Helen Craig we already know. Now we’re introduced to her resentful stepdaughter, Tina (Jan Wiley, from The Brute Man and She-Wolf of London); Tina’s simpering fiance, Arthur Wallace (Howard Banks); Walter’s spiritualist nutjob sister, Delia (Minerva Urecal, of The Ape and The Ape Man), and her deadbeat husband, George Philips (Murder by Invitation’s J. Arthur Young); Walter’s best friend, Tony Weldon (George Eldredge, from Calling Dr. Death and Voodoo Man); and Cedric (Norman Willis, of Voodoo Woman and The Iron Claw), the butler on assignment from Red Herrings Union Local 64. Trayne has a chance to do no more than ask a few preliminary questions and form a few preliminary suspicions (most of the latter revolving around Cedric) before something happens to reset the terms of the investigation at the most fundamental level— Walter Craig comes home. He’s in a weird catatonic state, though, awake, mobile, and in some sense conscious, but totally incommunicative and seemingly bereft of independent will. Dr. Bruhling (Lawrence Grant, from Daughter of the Dragon and The Mask of Fu Manchu), the neurologist who examines Craig, declares that he is suffering from “cortical paralysis,” by which he means literally that the cells of Craig’s brain have been paralyzed. That’s a really neat trick, if you’re asking me, since brain cells aren’t normally supposed to be capable of movement in the first place. Perhaps Walter Craig’s brain hails originally from Planet Arous?

Bruhling also avers that no mere accident could induce cortical paralysis. Craig would have to have been placed under anesthesia, with certain special chemicals added to the gas mixture in exactly the right proportions at exactly the right time. That means Trayne still has a crime to solve, and it also means that he has at least one clue. After all, the process Bruhling describes would require considerable specialized knowledge and considerable specialized equipment, so the culprit can only be someone who either has or has access to both. Trayne sets Peterson on the hunt for shady doctors and shady purchases of medical gear, while turning his own efforts to examining the mansion and its grounds. He finds footprints in the garden leading to the window through which Craig was almost certainly returned to the house, footprints that perfectly match Arthur Wallace’s overshoes. He collects reports from various sources describing all manner of suspicious activity around the house on the night of Craig’s homecoming, in which practically everybody under the mansion’s roof can be implicated. But mostly what he discovers is that he has the hots for Billie Hilton something fierce, and if Trayne would put half as much effort into solving the crime as he puts into figuring out whether she feels the same way about him, then this movie would have a hard time making it past the half-hour mark. The stakes rise considerably, however, when Craig regains enough of his willpower to begin roaming around in his trance-like state, attacking people with kitchen knives, and when a tip from Peterson leads Trayne and Billie to an abandoned house in the countryside (which I think is the Lorenz place from The Corpse Vanishes) with a zombie-like denizen of its own.

I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a horror or mystery film that did a worse job of integrating its romance subplot than The Living Ghost. It’s bad enough that they’re doing the whole “she detests him immediately— I guess she must be his love interest” thing, but when you see how unconcernedly Trayne takes time out to put the moves on Billie even when they’ve been cornered in a basement by someone who may or may not be trying to kill them, it becomes absolutely maddening. The comedy bits (look, it’s an old Monogram programmer— you knew there were going to be comedy bits) are inserted with similar artlessness, most of them in one big, indigestible blob at Trayne’s office, and in the case of the motor-mouthed customer who speaks in unintelligible argot, I’m not even completely sure what the joke was supposed to have been. The way these elements are grafted onto the main story, there’s simply no chance of them doing anything but to get in the way of the stuff we’ve come to see. What’s really frustrating is that The Living Ghost’s horror and mystery elements by themselves are fairly well handled, at least by Monogram’s usual standards. Sure, the cortical paralysis bit makes no real-world sense whatsoever, but having the presumed murder victim wander back into the story as an occasionally knife-wielding pseudo-zombie is an interesting touch. Also, despite the pile of impossibilities and near-impossibilities necessary to make it work, there is a definite internal logic to the villains’ plot once its details and motivations come to light. Simply shifting the setting from some unnamed American town to Porte au Prince would have solved the vast majority of this movie’s credibility problems at a stroke. Dial back the love story after that, and you might have a halfway decent little potboiler.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact