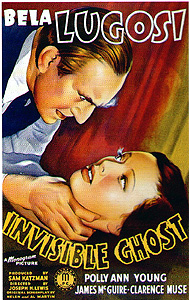

The Invisible Ghost/The Phantom Killer (1941) -**

The Invisible Ghost/The Phantom Killer (1941) -**

As is well known, Bela Lugosiís career took a major nosedive after the mid-1930ís. When horror films came back into vogue in 1939, Lugosi had the damnedest hard time getting his old bosses at Universal to give him a job that was worth a shit. Sure, there was Son of Frankenstein, but that was pretty much it; even his roles in the two subsequent Frankenstein films amounted to little more than mid-sized supporting parts. The minor studios, on the other hand, knew he still had some serious box office potential, especially after factoring in the lower overhead with which outfits like Monogram and PRC generally operated. Monogramís Sam Katzman signed Lugosi for a nine-picture deal in the early 40ís, by which point the one-time star was becoming increasingly disgusted with Universal, and while the Katzman pictures could hardly be described with any epithet more favorable than ďentertainingly awful,Ē they at least provided Lugosi with what he was no longer getting from the big boysó a succession of honest-to-God starring roles. The Invisible Ghost/The Phantom Killer was the first of these movies to see release. Conventional wisdom has it that it is the most lucid and coherent of the lot, but believe me, that isnít saying very much.

We can tell right off the bat that something isnít quite right about retired doctor Charles Kessler (Lugosi). Itís his wedding anniversary, and Evans the butler (Clarence Muse, from Black Moon and Soul of a Monster) is serving him and his wife the first course of their celebratory dinner. But thereís a false note in this symphony of marital bliss, for Mrs. Kesslerís chair is empty despite her husbandís seemingly oblivious efforts to make conversation with her. And wouldnít you know it, itís right in the middle of this surreal observance that young Ralph Dixon (John McGuire) shows up to pay a visit to Kesslerís daughter, Virginia (Polly Ann Young). Actually, itís a good thing for us that he does, because his arrival forces Virginia to explain that her dad always has candlelit dinner with an empty chair on his anniversary, and that heís followed that routine ever since the night her mom ran off with another man. Itís the only time of the year when he lets it show how deeply her desertion has affected him.

Meanwhile, back in the kitchen, Evans and Jules the gardener (Ernie Adams, from Return of the Ape Man and Jungle Captive) are talking with the new maid (Voodoo Manís Terry Walker) about some other eerie goings-on in the Kessler house. Evidently there have been at least a couple of murders among the servants in recent months, and nobody has a clue as to who might be responsible. Now that raises the compelling question of what in the hell could possibly have made even as tough and brassy a dame as Cecile Mannix want to take a job there, but the new domestic has her reasons. Up until recently, she was seeing Ralph Dixon, and the way she reckons it, his frequent appearances at the Kessler place offer her a solid opportunity to win him back from Virginia. In fact, Cecile makes a move on him that very night, but Ralph tells her in no uncertain terms that she hasnít got a prayer; he never loved her, heís very happy with Virginia, and ďnothing is going to stand in the way of my happinessó not even you.Ē And if you think you smell a plot point when Evans overhears their confrontation out in the garden, then your nose is even keener than you realize.

When Jules goes home that night, the first person he checks in with is not his wife (Ottola Nesmith, from The Seventh Victim and The Leopard Man) but Kesslerís (Betty Compson). This is not because Jules is the man with whom she skipped out on Charles all those years ago. (Even Mrs. Kessler has better taste than that.) Rather, sheís living in the gardenerís cellar because Jules was the first person on the scene when her new boyfriend wrapped his car around a tree on the road away from the Kessler house, killing himself and dealing Mrs. Kessler a blow on the head that left her noticeably feebleminded. What made Jules decide to hide her in his basement for the next several years instead of taking her either back home or to the nearest hospital? I havenít the foggiest notion. Nor can I offer an intelligible explanation for why Mrs. Kessler (who apparently believes herself deadó at least some of the time) periodically sneaks out to skulk around the grounds of her erstwhile home, or for why Charles Kessler drops into a fugue state every time he spies her doing so, and wanders off to smother one of his servants with his dressing gown. Thatís what happens, however, and when the long-missing woman shows up this time, itís Cecile who winds up on the sharp end of her bossís homicidal activities.

This is where that argument Evans overheard comes back to haunt Ralph. When the police inspector (George Pembroke, of Black Dragons and Bluebeard) shows up to investigate the latest crime at the Kessler mansion, he finds out all about Ralphís past history with the deceased, and about his circumstantially incriminating final words to her on the night of her death as well. Ralph is unable to account for his movements during the hour when the medical examiner believes the murder took place, and before you know it, heís on his way to the electric chair. Neither Kessler nor Virginia is able to persuade the governor to order a stay of execution, and thatís the end of that.

Ralph has a brother, though, a twin by the name of Paul (also John McGuire) who had been living in South America. Paul rushes north to see the Kesslers as soon as he hears that Ralph is in trouble, and though he gets there too late to contribute to his brotherís defense, he does make the acquaintance of Virginia and her father, and enlist them in his efforts to discover the killerís true identity (all concerned having no doubt whatsoever that the law has come crashing down on the wrong manís head). To that end, Paul moves into a spare bedroom at the Kessler place, leaving him perfectly positioned to put the pieces together when more crimes are committed under the ex-doctorís roof. At first, everybody seems to think Evans is the most likely suspect (Ďcause, you knowó ďthe butler did itĒ), but then Kessler receives a visit from his wife while the cops are on station at his house, and lapses into his usual murderous trance. Oddly enough, Charles snaps out of it in the middle of trying to strangle Paul, at the very moment his wife keels over dead for no apparent reason in the next room.

The Invisible Ghostís most striking aspect is the sense one gets while watching it that it takes place in some strange alternate reality where the laws of cause and effect as we know them simply do not apply. Though it is true that reasons are given for most of what goes on during its somewhat creaky 62 minutes (youíll swear itís a lot longer than that), not a single one of those reasons could possibly produce the outcomes depicted. Mrs. Kessler runs away with another man but, unbeknownst to her husband, is stopped from completing her elopement by a serious auto wreck; the woman is taken in by her gardener, and is hidden away not just from her husband (who might plausibly be expected to harbor a certain amount of ill feeling toward her), but from the entire world as well; the woman, now mad, periodically escapes and lets herself be seen from the windows of her old house; Charles Kesslerís sightings of his vanished spouse drive him temporarily insane and lead him to kill his servants. If this line of reasoning produces in you any response more articulate than a spluttering ďHuh?!Ē then you are obviously just as far out of your fucking gourd as Mrs. Kessler is. You will also note that this movieís title is singularly inappropriate, as the film features nary a ghost, invisible or otherwise. Nor can we even say that Kessler interprets his periodic visits from his wife as a haunting, because he is depicted most explicitly as believing that sheís still alive somewhere, and that one day sheíll get tired of Mr. Homewrecker Guy and come back to him!

What we can say in The Invisible Ghostís favor is that it makes interesting use of Bela Lugosi. Though he is indeed the killer, his character is unaware of that fact, and Charles Kessler is shown to be a decent and gentle man otherwise. This is far removed from what we generally expect from Lugosi, and the actor does a decent job with the role. In fact, from what I know of his personality, itís tempting to ask whether Lugosi himself might have wished his rendering of Kesslerís hapless befuddlement had been a bit less convincing. The best performanceó and the biggest surpriseó comes not from Lugosi, however, but from Clarence Muse. Itís a rare thing indeed to see a movie of this vintage that allows a black actor such generous measures of both screen time and dignity. When you consider that The Invisible Ghost was made the same year (and for the same studio) as King of the Zombies, you really understand what a lucky break Muse got here, and itís refreshing to see that he was able to make so much of the role. His understated delivery and perfect timing even salvage a couple of comic relief moments, as when he learns what drew Kesslerís latest cook to sign on for such a notoriously risky engagement. From what Iíve read, I gather that Muse wasnít always so fortunate. You have to wonder that one of his meatier and more rewarding gigs was playing the butler in a Monogram horror flick.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact