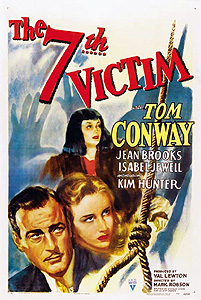

The Seventh Victim (1943) ****

The Seventh Victim (1943) ****

It may not be the best of the bunch (I give that crown to Cat People, hands down), but The Seventh Victim illustrates better than any other film the amount of creative freedom Val Lewton’s B-picture department was given by the bosses at RKO. When you take a good, close look at horror movies from the 1940’s (the American ones, anyway) one of the most obvious potential themes is conspicuous by its absence— the devil and his disciples. Today, you can’t draw a pentagram on the wall in the horror section of your neighborhood video store without scrawling across the box of at least a few movies about Satan or Satan-worshipers, but scarcely a one of them will have been made between 1935 and the late 1950’s. And considering the extent to which the Production Code Administration was created to be the lapdog of the Catholic Legion of Decency, this tendency to shy away from the devil while the former body was in power is easily understandable. But then out of nowhere comes The Seventh Victim, which not only has a Satanic cult playing the role of the villain, but credits that cult with a complex, non-caricatured theology to boot! It’s enough to make you wonder whether Joseph Breen (who was in charge of the PCA at the time) called in sick the day the movie was screened for his office.

Mary Gibson (Kim Hunter, later of Bad Ronald and Planet of the Apes) is an eighteenish girl who attends some private school or other in what is probably New England. Mary’s parents are both long dead, so her tuition has always been paid by her big sister, Jacqueline (Jean Brooks, from The Crime of Dr. Crespi and The Leopard Man), whose ownership of the La Sagesse cosmetics company means that she has plenty of money to throw around. But one day the headmistress (The Invisible Ghost’s Ottola Nesmith) calls Mary in to see her after class to inform her that there has been no word— nor payment, either— from Jacqueline in several months. The headmistress doesn’t want to be a hard-assed bitch about this, but she’s not running a charity here, and if nobody’s paying her way, Mary will either have to take up an assistant teaching position to earn her keep or leave the school. Actually, Mary has a third course of action she’d rather pursue; if the headmistress will allow her to return next semester, Mary wants to go to New York to see if she can figure out just what in the hell has become of Jacqueline. The headmistress agrees, and the girl heads out on the train to the Big Apple that very evening.

Mary hasn’t got many clues on which to base her investigation. Her sister is considerably older than her, and has never been particularly good about keeping in touch. Mary figures her best bet is to head over to the La Sagesse factory and have a talk with Jacqueline’s partner, Ester Redi (Mary Newton). The thing is, though, that Redi is no longer Jacqueline’s partner— evidently Jacqueline sold her the company at about the same time that she was last heard from at the school. And Jacqueline seems to be no better at maintaining her professional ties than her familial ones, as Redi hasn’t had much contact with her ex-partner since taking over La Sagesse. All that keeps Mary’s first attempt to track down her sister from coming up completely bust is one of Redi’s employees, a girl named Fran Fallon (Isabel Jewel, whom we’ve also seen— albeit very briefly— in Man in the Attic), who tells Mary that she saw Jacqueline at Dante, a little Italian restaurant nearby, just last week.

The restaurant in question proves to be more than just an eatery— it’s more like an English pub, with a dining room downstairs and dormitories for rent on the upper floors. Upon interviewing the owners, Mary learns that her sister didn’t just stop in for dinner, but went so far as to get a room. But oddly enough, Jacqueline never moved in as most people would define the term, but merely dropped off a little of her stuff, had the locks changed, and disappeared. She’s never missed a rent payment, though, so her landlords just shrugged their shoulders and let the issue drop. Mary succeeds in sweet-talking the owner’s wife into having her husband open up Jacqueline’s room, and all three are shocked and horrified at what they discover inside. The room is entirely unfurnished apart from an austere wooden chair in the center of the floor, and a skillfully tied noose hanging from the ceiling above it!

Not knowing what else to do, Mary goes next to the police to file a missing person report. While she’s at the station, she encounters a private detective named Irving August (Lou Lubin), who tries to talk her into hiring him to track down her sister. Mary doesn’t have the $50 August requires as a retainer, though, so she turns him down and heads off on her own. But a funny thing happens after she leaves the police station. A big, bulldog-like man accosts August and tells him that he’ll forget all about Mary Gibson and her missing sister if he knows what’s good for him. Yeah, well if the big guy knew what was good for him, he wouldn’t have been so obvious in his intimidation tactics; August is one contrary bastard, and this mysterious warning is enough to make him want to take up Mary’s case pro bono. His snooping reveals, among other odd things, that Jacqueline didn’t really sell La Sagesse to Ester Redi, but rather gave it to her free and clear. When Mary hears that, she becomes determined to have a look around the place, and she convinces August to accompany her for a little after-hours breaking and entering. Something goes horribly wrong, however, in that the two prowlers get separated when the night watchman turns up, and by the time Mary finds the detective again, somebody has stabbed him in the gut. And as if that weren’t enough, the whole situation is given an extra tinge of the sinister when Mary later finds herself riding in a subway car along with two dark-suited, sunglassed men (it’s got to be well after midnight by now) who initially appear to be helping an inebriated buddy of theirs get home, but who, on closer inspection, prove to be lugging the body of Irving August off to who knows where.

It’s at about this point that Mary meets up with a lawyer named Gregory Ward (Hugh Beaumont, from The Human Duplicators and The Mole People). Ward is also looking for Jacqueline, and for reasons very similar to Mary’s own— he’s her husband. Mary didn’t even know her sister had a boyfriend! Teaming up with Ward brings Mary into contact with a psychiatrist named Louis Judd (Voodoo Woman’s Tom Conway, seen here in an unexpected reprise of his role in Cat People), of whom Jacqueline is apparently a patient. (Mary never discovers this, but it turns out that Ward is paying Judd for Jacqueline’s treatment, even though he knows the doctor is having an affair with her.) Another person who proves to have known Jacqueline is a struggling poet who likes to hang around Dante, a man by the name of Jason Hoag (The Curse of the Cat People’s Erford Gage). Jason, too, wants to help Mary find her sister, and it is his connections that ultimately pay off. He introduces Mary to the social circle in which Jacqueline moved, and it is immediately clear that something isn’t quite right about them. You can say that again. These new friends of Jacqueline’s are bound together by their devotion to Satan; what’s more, virtually every minor character to whom we’ve yet been exposed— right down to Fran Fallon— is a member of the cult. Jacqueline herself joined up about a year ago, but became disillusioned. This bunch is kind of like the mafia, though— once you’re in, you can never really get out. And now that Jacqueline wants out, the cult’s unholy scriptures dictate that she must die.

This is where my favorite aspect of The Seventh Victim comes into play. Jacqueline’s cult is scarcely less ruthless than any we’ve seen elsewhere, but there is a big difference between them and your run-of-the-mill circle of devil worshipers. Though the cult is quite clear on the point that the penalty for apostasy is death (a penalty which has been imposed six times over the course of the order’s history), its members are also rigidly committed to a life of non-violence. This means that they can’t directly kill Jacqueline Gibson. All they can do is kidnap her, provide her with the means of ending her own life, and try to get her to do so through classic brainwashing techniques. The scene in which the cultists place their lapsed sister in a big, comfortable armchair with a glass of poison in front of her and harangue her all night long to drink from it is a brilliant piece of work. It is, for me, the crowning glory of an exquisitely complex and masterfully crafted film. I’ve seen very few movies that do such a terrific job of gradually cutting the ground of reality out from under their characters’ (and their audiences’) feet without resorting to the surreal or the overtly supernatural. From the moment Mary sees that noose hanging in her sister’s room at Dante, and realizes that Jacqueline has led a far more complicated and unconventional life than she had begun to imagine, it is all but impossible to be sure who can be trusted, how extensive the conspiracy surrounding Jacqueline is, or indeed even what its ultimate aims are. Meanwhile the Satanists are dealt with in a way that might actually be unique in the realm of horror cinema. Their beliefs and agenda remain shady throughout, but enough hints are dropped to make it clear that these are not the apocalypse-invoking, evil-for-its-own-sake types that we are accustomed to seeing in the movies. Furthermore, Satan himself never enters the story at all; there is no mystical showdown, no last-minute closing of a portal to Hell, not even a ritual sacrifice to be averted in the climactic scene. The devil is present only in his followers’ faith in him, while those followers spend far more time running their businesses and tending to their social lives than they do in active worship of the Prince of Darkness. This may be what shielded The Seventh Victim from the PCA, though really it is far more subversive than the conventional handling of the subject. By presenting the devil worshipers in such a prosaic light, the movie has the effect of normalizing them, making them seem like practitioners of an odd but perfectly respectable religion. The greatness of this movie lies mainly in that it manages to make the Satanists seem threatening without making them demonstratively evil or putting any obviously legitimate infernal power into their hands. It’s a difficult trick, and the filmmakers execute it beautifully.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact