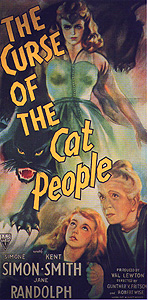

The Curse of the Cat People (1944) **

The Curse of the Cat People (1944) **

1944 was a big year for sequels. Admittedly, I haven’t seen all that many movies from that year, and the ones I have seen were, until now, all the product of but one studio, but even so, it has to be significant that every single movie I’ve seen apart from Cobra Woman with a 1944 release date was an entry in a series of some sort. So I suppose we shouldn’t be all that surprised to discover that the one sequel among the string of horror films that Val Lewton produced for RKO in the 40’s came out amid the company of movies like Jungle Captive and The Mummy’s Curse. And while we’re not being surprised by that, we should also take a moment not to be surprised by which one of the previous Lewton-produced horrors ended up spawning a sequel. Cat People, after all, wasn’t just the best of the bunch by a sizable margin, it was also the movie that got RKO’s ball rolling again in the horror genre. What might actually be worth taking surprise at is the extremely strange form this sequel took, but even that aspect of The Curse of the Cat People loses some of its power to shock when it is looked at in the context of the rest of Lewton’s output for RKO. Lewton was a man committed to confounding audience expectations; he’d already offered up movies about zombies and were-panthers which might not have been about those things at all, and he would go on to produce a nominal vampire flick which was quite up-front about featuring not a single real vampire. So it was at least in keeping with Lewton’s personality as a filmmaker to present a sequel that is worthy of the name only in that it revolves around the same central characters as the original.

A bit less than ten years seem to have passed since the events of Cat People. Oliver Reed and Alice Moore, the only central characters from the previous film to survive its unexpectedly violent conclusion (and who are once again played by Kent Smith and Jane Randolph), are now happily married. They also have a six-year-old daughter named Amy (Ann Carter) who is proving a bit of a challenge to raise. Amy is rather withdrawn and is extremely unpopular with the other neighborhood children. She makes up for her social isolation with an exceptionally vivid and elaborate fantasy life, and it is this that her parents— Oliver especially— find troubling. Alice’s concern stems simply from her wanting Amy to be happy (which she manifestly is not), but Oliver sees something more sinister at work in his daughter’s psyche. Oliver, remember, spent the last movie married to a woman who allowed her life— and those of the people around her— to be destroyed by what seemed to him to be an absurd and fantastic delusion, and when Amy talks about being friends with butterflies or the like, he can’t help but be reminded of Irena’s fatal conviction that she would turn into a savage panther if ever she were to experience physical love. Oliver’s strategy for dealing with the situation amounts essentially to trying to brow-beat Amy into becoming as sociable and unimaginative as the other kids. It’s a strategy that is obviously doomed to failure.

Case in point: Shortly after Amy’s birthday, the girl attempts to join some of her ostensible peers in a game of jacks, but the other children are still miffed with her over the chain of bizarre misunderstandings that led to them never receiving the promised invitations to her party, and they all refuse to play with her. While Amy is chasing after them, the pursuit leads her to a huge, decrepit mansion, from which the voice of an elderly woman calls to her. An unexplained summons from inside what may as well be a fairy-tale castle is more to Amy’s taste than a boring old game of jacks anyway, so of course she takes the bait and steps into the garden. When she is within perhaps five yards of the open window that seems to be emitting the voice, somebody tosses a small object out onto the garden path and tells Amy to take it. It turns out to be a ring (and not an inexpensive one, either) which the old lady in the house offers to the girl as a token of the friendship she wishes to have with her, and Amy is quick to ascribe a sort of quasi-mystical significance to it. This natural tendency is only magnified when the Reeds’ Jamaican housekeeper, Edward (calypso singer Sir Lancelot, who seemed to like playing small roles in low-budget horror flicks— he was also in I Walked with a Zombie and The Unknown Terror), tells her an island folktale about “wishing rings,” rare and wonderful baubles invested with the power to grant their wearer a single deeply desired wish. Amy wishes, as you might expect a lonely little kid to do, for a friend.

Sure enough, Amy acquires an invisible friend shortly thereafter. The trick is, though, that the invisible friend takes on a distinct face once Amy stumbles upon an old photograph of a beautiful woman in one of her father’s desk drawers. You guessed it— the woman in the picture is none other than Irena Dubrova (Simone Simon), Oliver’s “insane” first wife, and I bet you can also guess how Oliver is going to take it the first time he hears his daughter call her imaginary friend by the name of the woman whose memory still haunts him.

Meanwhile, Amy has gotten very close to the old lady in the mansion. Her name is Julia Farren (Julia Dean), and it turns out that she used to be a stage actress of no small repute. Julia lives with a much younger woman named Barbara (Elizabeth Russell, from Bedlam and The Corpse Vanishes), of whom she is extremely suspicious. As it gradually comes out that the dour and bitter Barbara is Julia’s daughter, but that Julia is unshakably convinced that her Barbara died early in childhood, Amy’s situation starts to look perilous indeed. Julia is almost certainly nuts, and Barbara is violently jealous of the affection she lavishes on Amy while denying her own daughter even basic acknowledgement.

I’ve got to give Lewton credit for this at least: he was not afraid to shake things up. On the other hand, I have to wonder whether there was ever a single fan of the original Cat People who saw this movie without any prior warning of what it was about who didn’t come out of it extremely disappointed. As a family-oriented fantasy movie (from back in the days when a script that put a child character in genuine, serious danger didn’t automatically remove a film from consideration for “family-oriented” status), The Curse of the Cat People is a respectable enough effort, and its setup certainly does follow logically from the development undergone by the characters of Oliver Reed and Alice Moore in Cat People, but I have to question the very idea of framing such a film as the sequel to a remarkably sophisticated tale of psychosexual horror. It just seems like the natural audience for The Curse of the Cat People would have been driven away by its association with the previous film, while those who went to see it precisely because of that association would have ended up feeling like they’d fallen for the biggest bait-and-switch yet perpetrated on the moviegoing public. On the whole, while it’s by no means bad, I think The Curse of the Cat People is very seriously compromised by this apparent lack of clarity on the part of its creators regarding just what it was supposed to be.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact