Bedlam (1946) **

Bedlam (1946) **

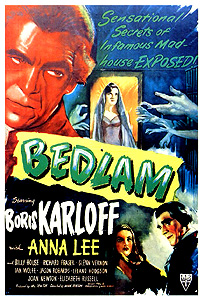

Under the guidance of producer Val Lewton, RKO had turned itself into a major player on the Hollywood horror scene with its first serious foray into the field since the 1930’s. The following year, 1943, arguably marked the peak of the studio’s horror cycle— at the very least, that year produced the most films in the genre. One result of this early success was that, in 1945, RKO’s leadership started giving Lewton enough money to hire a major star or two, and instructed him to spend it on Boris Karloff, who appeared in Isle of the Dead and The Body Snatcher that year. Despite their higher cost, these two movies proved to be the most profitable fright films yet for RKO, and for his next picture, Lewton was given an unprecedented $350,000 to work with. As it happened, this was a big mistake. The second Hollywood horror boom was in its waning days in 1946 (most commentators theorize that the American public had all the horror it could stomach in the experiences of its returning veterans of World War II, an explanation which seems reasonable enough to me), and even with Karloff onboard, Bedlam fared miserably at the box office. Not only would RKO not produce another horror film until 1951, Lewton would never make a movie for the studio again, and for all practical purposes, Bedlam marked the end of his career (though he did make one or two more cheap-ass movies for other companies before his death of a heart attack in the early 50’s). Considering this movie’s position in Lewton’s career, and considering also how good the man’s best work was, it’s a pity that Bedlam turns out to have far more in common with RKO’s insufferably preachy remake of The Hunchback of Notre Dame than it does with Cat People or The Seventh Victim.

The year is 1761— “The Age of Reason,” as an unsettlingly heavy-handed caption tells us. At the notorious St. Mary of Bethlehem madhouse (better known as “Bedlam”— the English can mispronounce anything), a young man is trying to haul himself up to the roof from an open garret window. Before he can do more than perform a few pull-ups, however, a soldier guarding the roof appears above him and steps deliberately on his fingers, causing him to plunge to his death on the street below. As the inevitable crowd gathers, the carriage of Lord Mortimer (Billy House, of Aladdin and his Lamp) arrives on the scene. This is a remarkable coincidence, for Mortimer knew the dead man— he fancied himself a poet and a playwright, and Mortimer had commissioned him to write a comedic piece for a party he was planning on throwing in a couple of weeks. Mortimer and his companion, a pretty young actress named Nell Bowen (Anna Lee, from The Man Who Changed His Mind and Jack the Giant Killer), are both furious to discover that Bedlam’s inmates are so poorly looked after that one of them could get out and fall off of the roof, but one suspects the two occupants of the carriage are incensed for slightly different reasons. In any event, Lord Mortimer insists that Master George Sims (Boris Karloff), apothecary general of Bedlam, pay him a visit the next morning to discuss the situation.

Now you might wonder what’s going on when Lord Mortimer has mental patients writing skits for him, but that’s only because you don’t live in 18th-century England. Bedlam, despite Sims’s title of apothecary general, scarcely qualifies as a medical establishment by modern standards. Basically, it’s just a big-ass holding pen for people who might otherwise impede the smooth functioning of society. But of equal importance, Bedlam is also a tourist attraction; for just two pence, anybody who wants to can walk in off the street and “see the loonies in their cages.” With such a lax attitude toward the treatment of the mentally ill, it’s scarcely surprising that Sims is willing to hire out those of his “patients” who have some artistic talent for the amusements of the upper crust. In fact, when Sims comes to see Mortimer, he suggests that he make good His Lordship’s loss by bringing a whole troupe of crazies to the party, and have them all perform something much grander than anything the dead man would have come up with. Lord Mortimer thinks that would be a splendid idea, and when Nell asks him just what this new plan will entail in practical terms, he sends her over to Bedlam to have a look at the place. Basically, she need but imagine the people she sees there acting out skits in his garden.

Nell goes to Bedlam, alright, but her impressions of the place are rather different from those of her sugar-daddy. When she sees the inmates squatting and crouching in the filthy straw that covers the floor of the main ward— and even more so when she gets a good look at the way Sims treats his patients— she is not amused, but sickened. She may deny the emotional impact of the scene upon her when she is questioned later by a Quaker stonemason (Richard Fraser, from White Pongo and The Picture of Dorian Gray) out in front of the asylum, but the truth of the matter comes out in no uncertain terms on the evening of Lord Mortimer’s party. Sims, as good as his word, has brought several of the “Bedlamites” over to entertain, and the show makes for about as sick and sorry a spectacle as you could ask for. Indeed, one of the poor nut-cases actually dies during the course of the performance due to his keeper’s callousness! (Incidentally, I’d like to take a moment here to point out that you will not die if somebody gilds you. Contrary to apparently popular belief, we humans breathe through our lungs, and what little gas-transfer does go on through our skins is homeostatically negligible. In fact, the only terrestrial vertebrates that do a significant percentage of their breathing through their skins are the amphibians— frogs, toads, salamanders, and the like. Dr. Science now returns you to the regularly scheduled movie review already in progress.) Nell leaves the party in a huff, and while she’s roaming the streets of London, she happens upon Hannay, the stonemason she met at the madhouse. The two of them get to talking, and the conversation soon turns to Bedlam, Sims, and whether there’s anything a single person can do to improve the lives of the asylum’s put-upon inmates. And what do you know, Nell suddenly realizes that there is something that can be done, at least if you happen to be the girl a member of the Greater London Council is trying to lure into his bed.

Taking advantage of her relationship with Lord Mortimer, she talks him into putting before the council a bill of humanitarian reforms for Bedlam, and Mortimer immediately calls in Sims to lay out the plan. Sims, for his part, obviously doesn’t like Nell’s ideas, but the shrewd old bastard realizes that he can’t just say what he really thinks. So rather than give Mortimer his opinion that the inmates of Bedlam are no better than animals and ought to be treated accordingly, he makes a big show of agreeing that the proposed reforms would be the best thing in the world for the asylum. Then he makes his move. Sims begins by giving a rough estimate of what the reforms would cost on a yearly basis; then he reminds Mortimer that Bedlam is funded by London’s property taxes. Finally, he “subtly” reminds Lord Mortimer of just how much property he personally owns in and around the city— that is to say, how much more in taxes he personally would have to pay in order to finance humane living conditions for a bunch of lunatics who, Sims assures his host, are too far gone to care about such things anyway. Inevitably, Nell’s bright idea never makes it out of Lord Mortimer’s drawing room. Nell, disgusted, breaks off her relationship with the fat, selfish, old bastard, and goes back to her old flat downtown.

This is where the trouble starts for Nell. Lord Mortimer is no grudge-holder, and he actually finds it rather charming when Nell starts pulling clever stunts calculated to make him look like an ass when campaign season for his seat on the council begins a few days later. He just doesn’t see it as a serious threat to him to have Nell out in the streets pretending to try to sell her pet parrot, which she once, as a joke, trained to say, “Lord Mortimer is like a pig— his brain is small, and his belly big.” Who, after all, is going to pay heed to the opinions of a bird? Sims, however, has a rather different take on the situation. It is his contention that Lord Mortimer could find himself in real trouble come election day if he allows himself to become a figure of ridicule. Not only that, Sims has seen Lord Mortimer’s opponent, John Wilkes (Leyland Hodgson, from The Invisible Man’s Revenge and The Frozen Ghost), talking to Nell, and he rightly believes that the would-be social activist has sold Wilkes on her plan to clean up Bedlam. This means that Sims now has just as much reason to want Lord Mortimer reelected as the candidate himself does, and the apothecary general soon has his old friend convinced that something must be done about Nell. Sims’s plan? Why, he’s going to get her committed to Bedlam, of course. All he needs from Lord Mortimer is his signature on a complaint-for-commitment form, and then he’ll just sit back and let Nell’s own eccentricities do the real work for him.

Needless to say, Sims’s scheme is successful. Just about everybody has a wacky streak, after all, and under the right circumstances, in the right atmosphere, a wacky streak can easily enough be made to look like evidence of a disordered mind. Sims may have miscalculated, though. First of all, Nell still has friends on the outside, in the form of Hannay the stonemason and John Wilkes— and considering that the latter is a well known and fairly powerful man, while the former is a moral exemplar and an extremely persuasive speaker, both could prove very effective allies. But equally important are the friends Nell makes among the Bedlamites themselves. Once inside Bedlam, Nell almost immediately begins doing what little is in her power to improve the lives of her fellow inmates, with the result that she becomes a very popular woman within the asylum’s walls. Naturally, the more successful Nell is in making the inmates’ lives more bearable, the less withdrawn and unresponsive they become, thereby striking directly at Sims’s justification for treating them the way he does. And naturally, the longer this goes on, the harder Sims is going to make life for his troublesome new patient. And that, my friends, is going to put him on the shit lists of a whole lot of potentially violent lunatics...

Horror movies with cloyingly “uplifting” moral messages have always gotten on my nerves, and Bedlam is no exception. The idea that the case of a single wrongfully committed woman could lead overnight to a sweeping re-conceptualization of appropriate treatment for the mentally ill is much too pat for me to swallow, as is the tidy end to which the smaller story of Nell’s confinement comes. Frankly, it seems to me that Bedlam reflects the floundering of filmmakers who suspect that their audience has lost its taste for horror, but who are determined to make one last dime before the market collapses completely. Even once Nell has been locked up in the asylum, it never seems as though anything particularly bad could actually happen to her, resulting in a movie that feels like it’s just going through the motions. This is especially disappointing here because Bedlam contains most of the necessary raw materials for an effective psychological horror film. Nell’s Kafkaesque plight really would be the stuff nightmares are made of if only Lewton and director Mark Robson (both of whom also contributed to the screenplay) didn’t go to such great lengths to convince us ahead of time that everything was going to work out okay in the end. Meanwhile, Boris Karloff is his usual excellent self, turning Sims into a perfectly believable villain; if he weren’t hamstrung by the tenor of the script and direction, Karloff would be nearly as scary here as he had been in The Body Snatcher the year before. All in all, Bedlam is a well-made but gutless film, and it’s hardly surprising that it marked the end of the road for RKO horror in the 40’s.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact