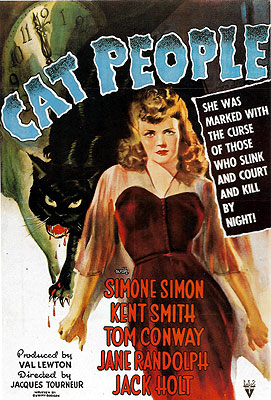

Cat People (1942) ****˝

Cat People (1942) ****˝

At this point, it’s scarcely a secret that “classic” status, in and of itself, earns a movie precisely zero respect from me. I think the great majority of the universally adored films of yesteryear are vastly overrated, and will happily argue the merits of Maniac or The Return of the Alien's Deadly Spawn over Bride of Frankenstein or The Old Dark House any day of the week. But once in a while, I do break my usual pattern, and close ranks with mainstream critical opinion. This is one of those times. Cat People was the first of nine psychology-driven horror films Val Lewton produced for RKO in the 1940’s. The movie not only won enduring critical acclaim for Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur, it also turned RKO into the first serious rival Universal ever had for the title of America’s premier horror studio. It also enjoys the distinction of being at the top of the list of a small handful of leave-it-all-to-the-imagination horror movies that I think really work. And in marked contrast to so many films of its era, it develops some real momentum during the final act. Though Cat People takes its sweet time getting started, once it gets rolling, it doesn’t let up.

This is the story of a young woman from Serbia, by the name of Irena Dubrova (All that Money Can Buy’s Simone Simon). She’s been living in America for quite some time, working as a fashion designer, but in all the months she’s been here, she has never developed even the rudiments of a social life. All that changes one day, when Irena meets a newspaper editor named Oliver Reed (Kent Smith, who would return to the horror genre many years later with The Cat Creature and The Night Stalker) at the zoo. Reed takes an instant liking to the shy, reserved European, and over the next couple of months, he makes sure to spend as much time in her company as she will allow. Indeed, not too much time has passed before Oliver falls in love with Irena, and asks her to marry him. The proposal doesn’t exactly get the reaction Oliver was looking for. Irena, though she professes to love Oliver, claims to be afraid to marry him— afraid for his safety! It seems that, in the remote mountain village where Irena grew up, the peasants told legends of a race of cat women, descended from medieval witches, who could take the form of black panthers when aroused by hatred, fear, or jealousy. What’s more, these cat women lived under a dreadful curse which caused them to murder any man they fell in love with at the first hint of consummation. Even so much as a kiss, and such a woman would immediately transform into a great cat and rip her lover to shreds. It’s an awfully strange story to tell a man in response to a marriage proposal, but Irena has very good reasons— she believes herself to be one of these legendary cat women.

Perhaps in Serbia that would have deterred Oliver, but Reed is an American, born and raised, and in America, we don’t go in for that sort of foolishness. No sooner has Irena finished her spiel than he launches into his, telling her that those stories are nothing but quaint superstition. There’s nothing wrong with Irena, or so Oliver says, except for the fact that she actually believes the legends. It sounds a little better— a bit less condescending— when Oliver says it (although I’m sure women were used to being condescended to in 1942, and accepted it as one of the occupational hazards of dealing with men), and Irena’s mind is put at ease at least sufficiently for her to agree to the marriage. All she asks of Oliver is that he be patient with her, and give her time to straighten out her head. The collected neuroses of an entire lifetime are not easily cleared away, you know.

But no matter how much time passes, Irena never seems to get any better. After two whole months without having so much as kissed her on the forehead, Oliver decides the time has come to call for backup. He talks Irena into seeing a psychiatrist, and then sets about finding one for her. At the recommendation of his friend Alice Moore (Jane Randolph, of Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein), who works with him at the newspaper, Oliver sets Irena up for an appointment with Dr. Louis Judd (Tom Conway, from I Walked With a Zombie and The She-Creature). This first appointment goes fairly well. It may not accomplish very much, but what do you expect from the very first session? But that first session is also the last. When Irena comes home, she finds Alice conversing with Oliver in the living room. Alice asks her how her appointment went, and Irena flies into a rage. She had no idea that Alice was the one who steered Oliver toward Dr. Judd, and she is furious that her husband would have shared such intimate information as her need for psychiatric treatment with another woman. Alice goes home after much apologizing, but it doesn’t do any good. Even if they hadn’t been already, Oliver and Irena would certainly be sleeping in different beds tonight!

This is where the trouble really starts. Not only does Irena refuse to go back to Dr. Judd, her relationship with Oliver starts coming apart at the seams. Their marriage becomes consumed by a hideous positive feedback loop in which her sexual frigidity, coupled with the emotional withdrawal that follows the revelation that Alice knows about her mental problems, leads Oliver to spend more and more time with Alice, intensifying Irena’s jealousy and increasing her emotional withdrawal still further. Irena begins spending most of her time hanging out at the zoo, watching the caged big cats— the black panther especially. When she isn’t thus occupied, she passes the time by spying on Alice, eyes peeled for any sign of a romance developing between her and Oliver. And then she takes advantage of a zookeeper’s carelessness to get her hands on the key to the panther’s cage. That spells trouble, any way you slice it.

And sure enough, Alice starts having run-ins with a black panther shortly thereafter. The question is, is this panther the one from the zoo, let loose by Irena to serve as her own private angel of vengeance, or is the cat Irena herself? Was she right all along about carrying with her some medieval curse from the mountains of Serbia?

What makes Cat People such a fantastic film is the fact that it builds equally strong circumstantial cases for either possibility right up to the very last scene, when the truth is finally revealed. When Alice is stalked by Irena on her way home from work one night, Irena’s sudden disappearance could mean that she’s turned into a panther, and is now causing that movement in the trees above the other woman’s head, but it’s equally possible that Irena has merely gotten a hold of herself and broken off the chase, and that the rustling of the overhead branches is the work of the wind and nothing more. A trail of muddy footprints that seem to change from the tracks of a cat to those made by a woman’s high-heeled shoes could just as well have been caused by Irena’s having walked on tip-toe part of the way to prevent the distinctive clicking of her heels on the pavement from giving her away to her quarry. Meanwhile, Irena’s behavior overall is certainly in keeping with what the legend has to say about the cat women of Serbia, but it’s also consistent with what we would expect from a mentally unbalanced woman in a fit of jealous rage. Many other movies have sought to employ this kind of ambiguity in the years since Cat People’s release, including most of Lewton’s subsequent thrillers. What prevents so many of these films from succeeding as Cat People does is their failure keep that ambiguity in balance. Some, like Cat Girl (an English knockoff of this movie, inexplicably made a full 15 years later), make too unconvincing a case for the possibility of a rational explanation for their mysterious goings-on. Others, like Lewton’s own Isle of the Dead, which sought to do for vampires what Cat People did for lycanthropy, go too far in the opposite direction, but still act as though they expect you to take the feebly and belatedly raised possibility of supernatural agency seriously. In Cat People, Lewton and Tourneur successfully strike this delicate balance, and the result is one of the finest achievements of 40’s horror cinema.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact