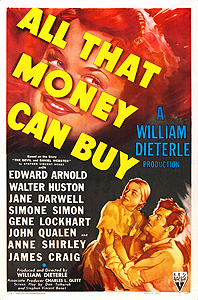

All that Money Can Buy / The Devil and Daniel Webster / Daniel and the Devil /Mr. Scratch / A Certain Mr. Scratch (1941) **˝

All that Money Can Buy / The Devil and Daniel Webster / Daniel and the Devil /Mr. Scratch / A Certain Mr. Scratch (1941) **˝

I’m honestly not sure what I expected from All that Money Can Buy. Maybe a condescending exercise in pious finger-wagging, like a Leaves from Satan’s Book for the 1940’s? Or perhaps a “feel-good” confection of folksy jingoism, built around a ludicrous misreading of Antebellum American history and culture? In any case, my hopes were not high. But I’ve become increasingly fascinated of late by the pre-Rosemary’s Baby cinema of Satanism and the occult, and there are precious few major-studio Hollywood movies from the Production Code era that deal in such themes at all, let alone put them front and center the way this one does. All that Money Can Buy was obviously too important a data point to be ignored any longer— so here we are, and trepidation be damned. It turns out that this movie is both of the things I worried about above, and a frequently infuriating paean to the innate superiority of the country bumpkin lifestyle as well. But it’s also several other, much more interesting things which combine to make it far more engaging and enjoyable viewing than I anticipated.

The time is April of 1840, the place a small settlement in rural New Hampshire. A young farmer named Jabez Stone (James Craig, from The Man They Could Not Hang and The Revenge of Dr. X) lives with his mother (Jane Darwell) and his lovely wife, Mary (Anne Shirley), on land he bought with money borrowed from Stevens the local banker (John Qualen, of Arabian Nights and 7 Faces of Dr. Lao). The Stones have not been very prosperous thus far, and it was apparently a pretty hard winter; Jabez has no money to give to Stevens for this month’s mortgage payment, nor anything else of value save a new calf and a few sacks of seed grain, both of which he was counting on to meet his own family’s needs in the coming growing season. His plight is common enough around here that a lot of the other farmers are talking about setting up a Grange chapter (the Grange is a cooperative organization that works to protect freehold farmers much as a union safeguards the interests of industrial laborers), but Jabez is all Rugged Self-Reliance, and prefers to go it alone.

Well… maybe not quite alone. When a particularly trying day leads Jabez to remark (in private, to nobody but himself) that he’d be willing to sell his soul to the Devil for about two cents, he is visited immediately thereafter by a stranger calling himself Mr. Scratch (Walter Huston, from Kongo and Transatlantic Tunnel). Scratch (like everybody else in the film) makes an ostentatious production of never coming out and admitting that he’s really Satan, but Jabez gets the point after perhaps fifteen seconds in his company. As so often happens, the Devil offers Stone a deal: his soul in exchange for seven years of good luck, with an option to renew at the end of the term. Then to demonstrate the magnitude of the luck he’s peddling, Scratch digs into the earthen floor of Stone’s barn, and… would you look at that! I’ll be dipped in shit if that isn’t a sack of lost Hessian gold! Not a little sack, either. No, this is enough gold to make Jabez at least as rich as that bastard Stevens. And Scratch places no conditions on the uses to which Stone may put this proffered prosperity, so it’s not like he’ll be required to turn evil, right? That, more than anything, is what Jabez tells himself when he signs Scratch’s contract in his own blood, and watches the fiend burn the date for Stone’s payment— April 4th, 1847— into the bark of a nearby tree.

Naturally the first thing Jabez does after revealing his windfall to his wife and mother is to drop in on Stevens and pay off the mortgage in full. In a slick bit of foreshadowing, Stevens realizes with some discomfort that he’s seen the mint markings on Stone’s antique coins somewhere before. Then the no-longer-poor farmer sets about buying some things that he and his family always sort of wanted, but could never really afford. Nothing too fancy, you understand— just some clothes a little nicer and prettier than the homespun stuff they’ve always had to settle for here, and a sturdy new plow there, and some extra livestock to make the farm more productive over yonder. Stone is generous with his newfound wealth, too, paying asking price for goods and services that he could probably have haggled down if he tried to, and tipping extra-handsomely. That sort of thing does wonders for his standing in the community, as does a chance encounter with US Senator Daniel Webster (The Secret of the Blue Room’s Edward Arnold) that affords Jabez a chance to show off his own hitherto unrecognized rhetorical gifts. Mary nevertheless remains leery of the family’s change in lifestyle, and Mom is openly disapproving. Then again, Ma Stone disapproves of pretty much everything except church, so why pay attention to her?

Jabez’s luck changes again a little later, in a subtle but important way. Thus far, his theoretically ill-gotten prosperity hasn’t cost anybody anything. In fact, Stone has raised the standard of living for everyone in the village by spending his money in his neighbors’ stores and workshops. But one day, Jabez lends a few sacks of seed grain to another farmer who’s gotten himself into financial trouble. And why shouldn’t he? He’s got plenty stashed away in the barn, and it would be a shame to see another once-proud freeholder fall into Stevens’s hands. Yeah, well the thing is, lending out that grain gives Stone power over the other farmer. Jabez has never had power over another man before, and he finds the sensation more to his liking than he consciously realizes. He gets more power, too, when a freak summer hailstorm wipes out the crops on all the local land save his own. The way Stone sees it, he’s just helping out the less fortunate when he takes on the most thoroughly ruined of his neighbors as field hands for his own harvest, but again there’s that thrill of being in charge. Obviously those hard-luck farmers will have to mortgage their land in order to rebuild, too, and the next thing Jabez knows, he’s in the banking business, competing with Mr. Stevens.

Now the money really starts rolling in. Stone becomes one of the biggest landowners in the village, big enough that guys who like to call themselves “squire” start treating him as one of their own. He hires a full-time maid so that his now-pregnant wife won’t have to wear herself out with housework. The party he holds in celebration of his son’s birth is the grandest and most exciting event in recent local memory, and no less a personage than Daniel Webster agrees to act as the child’s godfather. Jabez builds a lavish mansion on the hill overlooking his old house, and starts investing in horses fit for riding instead of just pulling plows or wagons. All the while, though, the moral cost of his good fortune grows more and more obvious. Jabez all but ceases working with his own hands around the farm, leaving everything to servants and hired labor. He starts hosting clandestine Sunday-morning poker games with the squires while his wife and mother are at church. As little Daniel (named, I assume, for his godfather) grows into the prime troublemaking years, Jabez lets him get away with pretty much anything. And above all else, there’s Belle (Simone Simon, from Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People). You remember that maid Jabez hired? Scratch evidently thought a man of Stone’s new station could do better, so he sent a succubus to Earth to assume the girl’s place. Being a succubus, Belle also takes over for Mary, if you know what I mean. Add it all up, and it’s no wonder Jabez loses every old friend he had— to say nothing of Mary, who packs up Daniel and goes to live with her mother-in-law at the old house. Mary also seeks out that other Daniel the next time Webster passes through, hoping that he’ll agree to put his legendary persuasiveness to work on Jabez. She’s not a moment too soon, either, because her husband is about to need the senator’s famous silver tongue for something more than his own edification. It’s been nearly seven years to the day since he made his infernal bargain, and Webster’s arrival on the Stone property coincides with that of Mr. Scratch. Jabez hasn’t got a chance on his own, but maybe an orator and attorney of Webster’s caliber can argue the Devil into tearing up a Faustian contract.

It’s awfully funny that Daniel Webster, of all people, would get pressed into service as the deus-ex-machina hero of a story like this one. Webster built practically his whole career sticking up for incipient plutocracy. He was the staunchest defender of the Second Bank of the United States during Andrew Jackson’s populist-inspired and ultimately successful campaign to dismantle it. As a lawyer, he was instrumental in guiding the Supreme Court’s early corporate law jurisprudence, forcefully arguing against the premise (which had enjoyed considerable support during the 18th century) that corporations received their special privileges only in return for acting toward the common good. As a delegate to the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention, he opposed extending suffrage to non-landowners, explicitly on the grounds that property was the only true and legitimate source of political power. As a politician, he put his considerable weight of influence behind a shameful deal that expanded the power of the Southern slave-owning aristocracy, even though he was a Northerner with no vested personal interest in preserving slavery. One might as well make Moses an early exponent of Wicca or John Locke a partisan for the divine right of kings as turn Daniel Webster into a hero of the common man.

That said, there is a logical reason (of sorts) for the implausible characterization. All that Money Can Buy was based on a short story by Steven Vincent Benet, which in turn was a reinterpretation of Washington Irving’s “The Devil and Tom Walker.” “The Devil and Tom Walker” had been a straight Americanization of the traditional Faustian soul-selling narrative, but in “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” Benet subverted the formula by introducing a way for the damned protagonist to squirm his way off of Satan’s hook. The meat of the story was the otherworldly trial at which Jabez Stone’s case is heard by a jury from Hell, consisting of early American history’s worst traitors, villains, and rogues (broadly construing “American history” to encompass all Anglo-Saxon involvement in the Western Hemisphere); the judge at this proceeding, fittingly, is John Hathorne, who presided over the infamous judicial travesties at Salem in 1692. Benet gave Daniel Webster the job of defending Stone because of his reputation as an unbeatable attorney, and the short story was in any case not much concerned with the sociopolitical milieu in which the characters lived. What we’re looking at in the movie, then, is a case of adaptation expansion gone awry. A feature-length film has to show the hardships that lead Stone to sell his soul. Nor can it just skip over the seven prosperous years granted to him by the Devil, or their accompanying slide toward sin and damnation. As a consequence, the film version must have something concrete to say about what hardship, sin, and damnation mean. And because movies in 1941 were first and foremost the entertainment of the masses, All that Money Can Buy’s creators had every incentive to frame those concrete conceptions according to the national mood— which, in a country still not quite free of the Great Depression, was decidedly hostile toward the kind of people on whose behalf the real Daniel Webster generally advocated. Such considerations also help explain the anachronistic subplot in which the Grange (which wasn’t founded until 1869) is put forward as the alternative to bargaining with Satan.

I must confess that it gave me a little thrill to see a mainstream American movie present laissez-faire capitalism as literally the Devil’s economics. I got a rather bigger one from Scratch’s riposte to Webster’s opening gambit before the trial, arguing that the contract with Stone was null and void because Scratch is a foreign prince for the purposes of US law, and therefore powerless to force a US citizen into his service: “Who has a better right [to claim American citizenship]? When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on the deck.” From beginning to end, All that Money Can Buy is shot through with the totally unsophisticated, totally uncritical patriotism of a seventh-grade history textbook. You’ve heard the narrative a thousand times: simple, moral country folk tame virgin wilderness through hard work and the grace of God, holding aloft the torch of liberty for all the world while they’re at it— “America! Shucks yeah!” But then this amazing statement comes along, this stark and unflinching indictment of the USA’s dual Original Sins. “When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on the deck.” What to make of it? On the one hand, it is Scratch speaking, and traditionally the Devil is the Prince of Lies. But it’s equally traditional that Satan lies most effectively by telling the truth, and nudging the listener to draw false conclusions from it. In any case, it’s shocking to hear a Hollywood movie of the early 40’s own up to the fact that the European conquest of the Americas entailed monstrous and indelible evils, whatever good may have come of the enterprise in the long run.

Thus far, I’ve been talking about All that Money Can Buy mainly in terms of its ideology— with ample justification, I believe. For one thing, this is among the most explicitly ideological movies I’ve ever seen from this era, often to the point of becoming almost insufferably preachy. Beyond that, the peculiar contortions of All that Money Can Buy’s ideology account for a big part of the picture’s interest. Nevertheless, we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that this is also a supernatural fantasy about a decent man who casts his lot with the forces of cosmic evil in a moment of desperation. Not to engage this film on that more basic level would mean short-changing both it and ourselves.

One reason why I’m willing to forgive All that Money Can Buy’s starchy didacticism is that it was almost certainly the price for getting the movie made in the first place. Among other things, the rarity of Satanic themes in 30’s and 40’s cinema should tell us that the Production Code Administration was doing its job; The Black Cat and The Seventh Victim were very much the sort of movies that the Legion of Decency and its allies had hoped to stamp out. But add a moral lesson so obvious that not even a dullard like Joseph Breen could miss it, and apparently “Do what thou willt” shall be the whole of the law. I mean, this movie got away with having a succubus in it, and what’s more, it got away with making it perfectly clear that Jabez is fucking her in preference to his wife! The unwontedly frank sexiness of Simone Simon’s Belle is a major point in the film’s favor, as is the menace she projects when interacting with characters other than Jabez. Above all, there’s one memorable scene where Belle takes Stevens as her dancing partner at the party Stone throws to cement his upwardly-mobile status, and that early hint of the banker’s own involvement with Satan pays off. It’s like something out of Mary Henry’s nightmare hallucinations in Carnival of Souls. Walter Huston’s Scratch is a fine interpretation of the Devil, too, the culmination toward which John Gottowt’s and Werner Krauss’s performances in their respective versions of The Student of Prague were building. Witty, charming, and personable, he nevertheless projects an aura of dangerous power and corruption. Finally, the introduction of judge and jury to commence the climactic trial scene is a miniature masterpiece. Scratch opens up a trapdoor in the floor of Stone’s barn that hadn’t been there a moment before, and up come his tribunal of the damned from the bowels of the underworld, each of the thirteen specters looking like his own distinct brand of Bad News. Even among that crowd, though, H. B. Warner (from Supernatural and The Phantom of Crestwood) stands out as Justice Hathorne. It’s a small role, but Warner is great in it, foreshadowing all the best sadistic jurists of the 70’s witch-burners. All that Money Can Buy is a challenging film, in that it subjects the viewer to a lot of irritating, clumsy crap on its way to the good parts, but those who accept the challenge will find significant rewards awaiting them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact