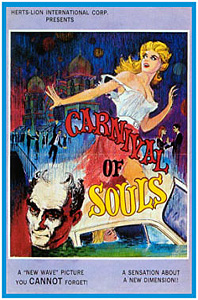

Carnival of Souls/Corridors of Evil (1962) ***˝

Carnival of Souls/Corridors of Evil (1962) ***˝

Over the years, I’ve gradually come to the realization that those horror movies I regard as being genuinely, exceptionally good tend to cluster at the far ends of the spectrum. I mainly favor the ones that leave me feeling as though I’ve been clubbed over the head with something big and heavy on the one hand, and those that might best be described as disorienting and eerie in a quiet, understated way on the other. At a guess, I’d say this is because the long years of intensive exposure have left me mostly immune to the relatively pedestrian shock tactics that fill most horror filmmakers’ bags of tricks. It’s damned hard to get to me with the standard “Boogabooga!” approach, but if you know which buttons to push, you can still disturb the hell out of me or give me a severe case of the creeps. And in my case, the right buttons to push in order to trigger the creeps mostly have to do with ghosts and hauntings. There’s a very good reason for this: they’re the only supernatural manifestations that I’m not totally convinced I don’t believe in. Demons and angels and ancient gods, vampires and witches and werewolves— these things can all make for a good story, but I’ve never in my life encountered one, and I don’t know anybody who has. I do know people who claim to have seen ghosts, though, and I personally have had a handful of experiences with that phenomenon which might best be called the Bad Place. Where am I going with all of this, you ask? To Carnival of Souls/Corridors of Evil, of course. One of the rare films that truly deserves the overused epithet of “cult classic,” Carnival of Souls— which sank like a stone upon its initial release— has acquired a good-sized underground following in the years since on the strength of an insidious spookiness that most people would scarcely believe possible coming from a movie that looks like it was paid for with funds salvaged from between the cushions of producer/director Herk Harvey’s sofa. Then again, Basket Case and Night of the Living Dead were made on Taco Bell budgets, too.

The movie begins on an extremely odd note, with a girls-against-boys drag race. Mary Henry (Candace Hilligloss, from The Curse of the Living Corpse— just about the only person in the film who was able to parley her appearance into something like an acting career) and three of her friends are out riding around in one of those friends’ cars when they are challenged to a race by a bunch of guys in a 20-year-old hotrod. The girl in the driver’s seat accepts the challenge, and the resulting race eventually leads both cars over a rickety bridge that is halfway through a series of extensive repairs. The two vehicles are neck-and-neck when the male driver— apparently by accident— clips his opponent’s fender, and the car carrying Mary and her friends goes hurtling through the makeshift wooden guardrail and into the turbid river below. The authorities are unable to locate the vehicle, but a bedraggled Mary eventually turns up on a sandbar directly below the bridge. The other girls, one assumes, were not so lucky.

Another safe assumption is that the loss of her friends has something to do with Mary’s eagerness to get out of town and never come back. Her strategy for achieving this end is to take a job way out west in Utah; in a rather surprising touch, she’s an organist by trade, and she has lined up a position playing for a church in some town with sufficient population and tax base to irrigate its way out of desert-hood. Of course, it’s a hell of a drive from Kansas to Utah, and we all know the kind of strange things that a long, lonely drive can do to a person’s mind, especially after it gets late enough. So maybe that goes some way toward explaining the feeling of foreboding that Mary gets as she drives past the darkened pavilion silhouetted on the western horizon by the last rays of the setting sun, and maybe it also explains the frightening apparition that confronts her once night has well and truly fallen: Mary sees a strangely cadaverous man watching her— impossibly— through the passenger-side window of her fast-moving car, a man who vanishes only to reappear standing in the road directly in front of her. There is, of course, no sign of him when Mary swerves to a stop on the shoulder of the wrong side of the road. Again, maybe it was all in her head— I’ve hallucinated stranger things during a long, exhausting drive in the dead of night— but I wouldn’t bet on it if I were Mary.

Strange visions and experiences continue to plague Mary at her destination. She gets a room at a sort of unofficial boarding house run by a Mrs. Thomas (Frances Feist), a woman perhaps 15 years her senior. There’s one other boarder— a rather smarmy man called John Linden (Sidney Berger)— but it isn’t him that Mary sees spying on her through the window and peering up at her from the bottom of the staircase. No, the man she sees watching her is definitely the guy she thought she saw standing in the road out in the desert. The thing is that nobody else sees him, even though both John and Mrs. Thomas at some point pass right by the place where he was standing mere moments after the sight of him frightens Mary back into her room.

The morning after her arrival, Mary goes to church to meet her new boss (Art Ellison). The minister seems a decent enough guy (well, for a minister, at least...), but he’s somewhat taken aback by Mary’s completely businesslike attitude toward her new job. He just can’t seem to wrap his mind around the idea that anyone would want to work in his church without becoming a part of its social and spiritual life. Nevertheless, Mary is a capable organist, and the preacher figures she’ll do nicely, even if she’s a bit peculiar. After showing her around the church, the minister mentions that he has to go out of town on an errand, and when Mary realizes his route will take him right past the pavilion she saw hulking on the horizon the night before, she asks to be brought along on the trip so that she can see the place by daylight. The pavilion proves to be a derelict carnival built beside what must be an artificial lake. The minister says the place hasn’t been used in years, and the condition of the fence that surrounds it certainly supports his story. Mary leaves with no more understanding of the power the old carnival holds over her imagination than she had when she arrived.

Mary has the next day off from work, but it ends up being far from relaxing for her. She continues to catch glimpses of the cadaverous man everywhere she goes around town, but that isn’t the strangest thing that befalls her. She heads out on a shopping trip around noon, and an odd feeling comes over her while she ponders whether or not to buy the dress she had been trying on. She thinks nothing of it at first, but then when she goes to the sales clerk to make her purchase, the other woman seems completely unaware of her presence. It isn’t just the clerk, either; everyone in the store behaves as though they can neither see nor hear her. And what’s more, Mary soon realizes that she can’t hear any of them, either! Horrified, she flees out onto the street, but the situation is no different outside, and for a short but harrowing stretch, Mary runs about through the town in a state of escalating panic at her inexplicable severance from the world. Then it all passes as suddenly and mysteriously as it came on. Mary’s still awfully unnerved, though, and when she sees the face of her phantasmal stalker on the man standing behind her at a water fountain in the park, she descends once again into hysteria. Fortunately for her, Dr. Samuels (Stan Levitt), the town physician, happens to be passing by when she begins her second big freak-out of the day, and he settles her down and leads her back to his office where he proceeds to get all Freudian on her ass.

The upshot of Mary’s talk with Dr. Samuels is that she is now hell-bent on paying a visit to the ruined carnival, having decided somehow that it holds the key to all the strange things that have been happening to her. Her hour of bush-league psychotherapy also brings her face to face with some aspects of her character she’d never really considered before— most notably her utter lack of interest in romance, which really seems to be just a symptom of a more general disregard for any sort of human relationship. This personal revelation becomes the key to the rest of the film; as the frequency and intensity of her paranormal experiences increase, the coldly rationalist Mary tries harder and harder (with less and less success) to force herself into relationships she doesn’t really want, on the theory that her terrifying visions of isolation from the world of the living and invitation to the world of the dead are her subconscious mind’s way of warning her that she has let herself become cut off from other people to a psychologically dangerous degree. Most notably, Mary makes herself succumb to the crude and boorish amorous advances of fellow boarder John Linden, a man whom she quite obviously does not like (and with good reason). When even this fails— in the most spectacular possible way— Mary drops everything, and drives straight to the old carnival, where she gets more out of her showdown with her subconscious than she bargained for. The Freudian explanation turns out to be just as full of shit as it sounds, and Mary’s troubles prove to be of an entirely greater order of magnitude than she had allowed herself even to consider.

It’s awfully slow going, and it frequently makes precious little sense, but I still think Carnival of Souls is one of the all-time great cinematic variations on the theme of the haunted person. To me, this is a much scarier concept than that of the haunted place. After all, you can always leave a house or a church or a water filtration plant if it becomes infested with ghosts, but if a malevolent supernatural agency latches onto you personally, then it becomes much harder to imagine a way out of your predicament. I think what makes Carnival of Souls work so well as a treatment of this idea is the character of Mary Henry. Mary is the exact opposite of most women in horror movies from this period. She has her share of screaming hysterics, but at bottom, she is strong-willed, hard-headed, and not given to fanciful or superstitious thinking. She trusts and relies on her own perceptions, but is well aware that her senses and indeed even her mind are imperfect instruments for apprehending the world around her. Knowing that her aloof, self-sufficient personality makes Dr. Samuels’s diagnosis of her problem plausible in general terms (even if his specifics are a bit on the silly side), she begins attacking that problem as if it were a purely psychological one. But she can never convince her intuitive mind that her preternatural experiences are all in her head, and I’m sure most people in the real world wouldn’t be able to, either. It’s very rarely that a movie even attempts to deal realistically with the psychological and emotional effects that this kind of confrontation with the seemingly impossible would have on a rational mind, and the number of films that succeed in doing so probably isn’t worth the bother of counting. When I watch Carnival of Souls, it’s this aspect that my mind latches onto, and the movie gets under my skin even in spite of the sometimes unconvincing acting, occasionally clunky dialogue, and almost complete lack of conventional plot development. Besides, the recurring image of the revenants dancing stiffly under the carnival’s main pavilion is creepy enough to be worth the price of admission all by itself.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact