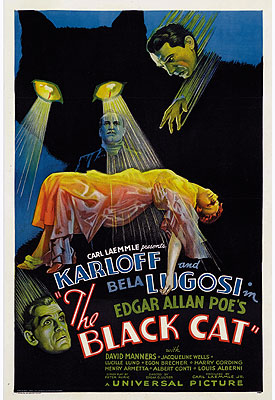

The Black Cat / The Vanishing Body / House of Doom (1934) -**

The Black Cat / The Vanishing Body / House of Doom (1934) -**

You know trouble is ahead when a movie’s main title display says it was “suggested” by an Edgar Allan Poe story. Not “from,” not “based on”-- “suggested by!” Or as I prefer to read that, “with a title pilfered shamelessly from an unrelated, much better story by...” And you thought they didn’t invent that sort of thing until the 1960’s. As you may know, The Black Cat/The Vanishing Body/House of Doom’s principal claim to fame is that it featured the first, and by most accounts best, pairing of 30’s horror kings Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. I tell you, if this is the best work the two of them did together, I can’t wait to see the worst!

The main question that springs to my mind while watching The Black Cat is “what in God’s name was writer/director Edgar G. Ulmer on when he made this?” The plot is bafflingly complicated, but the main point is that Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi) has just recently been released from the Russian P.O.W. camp where he spent the fifteen years since the end of World War I, and that he is now in the process of seeking out his former commanding officer, an architect and Satanist high priest (!) named Hjarmal Poelzig (Karloff), who sold out his garrison when the enemy surrounded his fortress, and is thus directly responsible for all those years the doctor spent in a Russian prison. But Werdegast’s beef with Poelzig doesn’t end there-- not by a long shot! It seems Poelzig also used the opportunity opened up by Werdegast’s imprisonment to steal his wife and daughter away. Poelzig now lives in a huge mansion of his own design, built on the ruins of his former fortress, and it is here that our story will unfold.

Of course, we’re not going to get anywhere in this film without some innocent bystanders to get caught up in the two men’s feud, and Ulmer provides them for us in the form of a young married couple named Peter and Joan Allison (David Manners, who had previously played opposite Lugosi in Dracula and opposite Karloff in The Mummy, and Jacqueline Wells, aka Julie Bishop, from Torture Ship, respectively). These peppy American love-birds are on their way to Gombos (the actors can’t seem to agree on how it’s supposed to be pronounced, but I’m inclined to favor Lugosi’s “Gawmbawsh” over Manners’ “Germbish”-- Lugosi may not have been able to speak English worth a fuck, but one would expect him to have a pretty good handle on Hungarian) via the Orient Express, when their path crosses that of Werdegast. The doctor has purchased a ticket on the same train, and he was mistakenly assigned to the Allisons’ compartment. The three of them talk for a while (Lugosi’s performance in this scene could be turned into a book called How to Overdo It), and it comes out in conversation that they’re all going more or less the same way. It is also revealed that Joan bears some kind of resemblance to Werdegast’s wife, a development that is just bound to get somebody into trouble later.

Before Joan’s looks have a chance to cause problems, though, trouble of a rather different sort engulfs Werdegast and the Allisons. Their bus from the train station overturns while rounding a bend in the road during a fierce thunderstorm, and the driver is killed in the crash. Joan ends up with a few injuries too, so it’s a good thing for her, in a sense, that the wreck occurred not far from the Poelzig mansion. And it is here, less than twenty minutes into the film, that the narrative structure of the script starts threatening to fall apart into a heap of rubble. The problem is that far too much is going on at the same time that nothing at all is happening. The gist of the whole mess is that Werdegast has come for revenge while Poelzig is perfectly happy to take him on, and that the ensuing battle will take place with Joan’s life as some sort of prize. Why Poelzig wants Joan is never really explained, nor for that matter is Werdegast’s desire to protect her. Along the way, we learn that Werdegast’s wife died shortly after Poelzig married her, and that the architect then embalmed her, stashed her body in a glass case in his basement, and married her daughter, Kaaren, in the older woman’s place. The strangest thing of all is that Kaaren doesn’t really seem to mind. We’ll also bear witness to some sort of Satanic ritual (at which Joan is to be the Devil’s sacrifice), the shadow of one of the major antagonists flaying the shadow of the other with the shadow of a scalpel, and an ill-conceived finale involving the hundreds of tons of TNT that were buried beneath the fort’s foundations during the war, which Poelzig has inexplicably wired up to an electric detonator in his basement. I have a hard time understanding how Poelzig could have come to be regarded as Austria’s foremost architect when he thinks it’s a good idea to rig his own home with a self-destruct system-- what, does he think he’s living aboard the starship Enterprise?

By this time, you’re probably wondering what any of this could possibly have to do with Poe’s “The Black Cat.” The short answer is: “Not a goddamned thing.” The long answer has to do with the fact that Werdegast has, for absolutely no reason beyond the need to excuse the title, an extreme phobia of cats, while Poelzig seems to have hundreds of the things-- all black, of course-- roaming around in his mansion. Just about every time Werdegast tries to start something with the architect during the first hour of the film, one of those cats wanders into the room and causes him to flip out, prolonging the movie by another fifteen minutes or so. It’s easily the flimsiest excuse ever for a movie to claim a Poe pedigree, and I can see why The Black Cat was released in England under the title House of Doom instead, while the stateside re-release some years later bore the title The Vanishing Body. (Do you suppose the latter title was an attempt to siphon off some of the audience from Monogram’s 1942 Lugosi vehicle The Corpse Vanishes, or might it have been the other way around?)

And when I use the word “excuse” in the previous paragraph, I do so quite deliberately. Having seen big returns on a modest investment with 1932’s Murders in the Rue Morgue, Universal were understandably eager to try the Poe gambit again. But producer Carl Laemmle was a clever man, and he knew that all the Poe he really needed was the title and a hook to hang it on. With that in mind, Laemmle agreed to let Ulmer make any old movie he pleased, just so long as it was called The Black Cat. For his part, Ulmer had no particular interest in Poe. What interested him was black magic, particularly as embodied by the notorious (and still living in 1934) Aleister Crowley. Not only is Hjarmal Poelzig quite transparently a caricature of the famous magician’s public image, The Black Cat’s plot is an enlargement and embroidery of a real incident. In 1923, a woman named Betty May Loveday went with her husband to study under Crowley in Italy. The Satanic ceremony depicted in the movie follows very closely Loveday’s description of rites in which she and her husband claimed to have participated at Crowley’s direction.

Not only that, other aspects of Hjarmal Poelzig’s character bear a striking resemblance to a second mystic, one with whom Ulmer was acquainted personally. This second man was Hans Poelzig, an engineer and architect with whom Ulmer had worked back in Germany. The real Poelzig had been hired to design and construct the vast city set for Paul Wegener’s The Golem/Der Golem: Wie Er in die Welt Kam, while Ulmer was employed as a silhouette-cutter on the same film. (It was his first paying job in the industry.) Poelzig’s eccentric ideas-- he designed his buildings in accordance with various magical principles, in an effort to get in touch with a Neo-Platonic spirit-world he called “the Other”-- made a big impression on Ulmer, and given that the director’s set designs for The Black Cat represented a deliberate effort to make them characters in the film the way Poelzig’s had been in The Golem, it seemed appropriate to give his mentor a nod in the script.

Of course, most people who talk this movie up know nothing about any of this, and care less about the story than they do about the teaming of Karloff and Lugosi as foes. It’s hard to see why. Lugosi is at the height of his powers as an actor here, and he’s still a big fucking joke. Okay, so he’s not nearly so laughable as he would become later, but whatever his accomplishments as a stage actor in his native Hungary, the man comes across as exactly what he is in his early American movies-- a guy delivering lines he doesn’t understand, memorized by rote in a language he doesn’t speak. Frankly, I don’t know whether to admire him for his audacity, or to ridicule him for entertaining, even for a second, the notion that this was a good idea. Karloff is rather better, but he seems somehow uncomfortable with his role, his dialogue especially. It would be understandable if he were-- nobody (except maybe Lugosi) could have delivered any of this dialogue without feeling a twinge of embarrassment.

But the thing that really knocks The Black Cat out of the picture as a serious film is the music. I have to wonder if the person who scored this puppy had even watched the damn thing! Every cliched musical cue in the book is on display here, all of them completely inappropriate to the action of the scenes to which they are set, all of them serving as nothing else could to undermine any attempt on Ulmer’s part to make The Black Cat work as the atmospheric suspense film he clearly thought he was making. Truth be told, all the misplaced violin bombast is probably the most enjoyable thing about this absurd little movie, next to the extremely strange story of its origins.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact