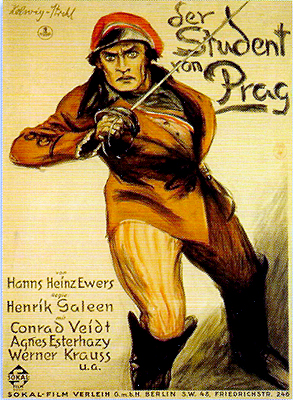

The Student of Prague/The Man Who Cheated Life/Der Student von Prag (1926) ***

The Student of Prague/The Man Who Cheated Life/Der Student von Prag (1926) ***

I’ve mentioned before that there was a whole lot of remaking going on in the early days of cinema— so much, in fact, that today’s oft-bemoaned remake vogue pales in comparison. And as we are about to see, it wasn’t just Hollywood compulsively repeating itself. Even in Germany, arguably the world capital of cinematic artistry between World War I and the early 1930’s, filmmakers were perfectly willing to imitate a good thing when they saw one. To focus (as is my wont) just on the horror genre, the Germans produced several silent versions each of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Picture of Dorian Gray (most if not all of them now believed lost), but naturally it was one of their own authors whose works seem to have inspired the most reiteration. Hanns Heinz Ewers may be little-known to English speakers, but he clearly struck a nerve with filmmakers in his home country, for his 1911 novel, Alraune, has served as the basis for four German movies (plus one Hungarian version), and his screenplay for the pre-Great War horror film, The Student of Prague (adapted and enlarged from E. T. A. Hoffmann’s short story, “Sylvestrenacht”), accounts for a further three. Henrick Galeen’s The Student of Prague is the second of the latter triad, and is generally regarded as the best version. Though it very closely resembles the 1913 interpretation directed by Stellan Rye, it is a much more mature film, and it benefits from reuniting the actors who had played the two memorable villains in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Somewhere in the woods outside of Prague, there stands a weathered stone monument, dedicated to a young man named Balduin, “who gambled with evil and lost;” this film is the story of that gamble. Balduin (Conrad Veidt, from The Man Who Laughs and The Hands of Orlac) is a popular lad among his classmates at the university, but he has grown dissatisfied of late with his hell-raising lifestyle. For one thing, it’s expensive, and Balduin is rapidly running out of money. But beyond that, it’s kind of a lonely existence, and Prague’s most notorious party boy is beginning to recognize the appeal of settling down and taking a wife. Liduschka (Elizza La Porta), the flower-seller who often hangs out at the university students’ favorite beer hall, would very much like to be the girl with whom Balduin does that settling down, but he seems to be just barely aware of her. Balduin may be ready and able to use his formidable fencing skills in Liduschka’s defense when one of his classmates gets too rowdy with her, but his motivation is general chivalry, and not any particular affection for the girl herself. Then one afternoon, Balduin has a brief meeting with a stranger who calls himself Scapinelli (Werner Krauss, of Waxworks and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), and lets slip a careless utterance that will change his life. Evidently Scapinelli has heard Balduin’s classmates talking about the lad’s money troubles, because he initially offers to lend Balduin a sizeable sum at a comfortable rate of interest. Balduin waves him off, though, remarking that if Scapinelli really wanted to help him, he’d find him a rich heiress instead.

That’s just what the mysterious man does. At that very moment, Count Schwarzenberg (Fritz Alberti, from Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge) is organizing a hunt on his vast estate outside of town, and among the participants are his daughter, Margaret (Agnes Esterhazy), and her fiance, Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg (Ferdinand von Alten, of Warning Shadows). Scapinelli, perched atop a hill, sees the hunt ride out from Castle Schwarzenberg, and he reveals his true nature for the first time by casting a spell over Margaret’s horse, enabling him to seize control of it away from its rider. Scapinelli rigs it so that the young countess rides right by Balduin on his way home to his flat, and then has the animal throw her from its back right in front of him. Balduin rushes to get Margaret clear of the horse’s hoofs, and once the crisis is past, both parties realize that they find each other rather appealing. The count and some of his men arrive right about then, however, and the scene is cut short before Balduin can do more than learn the girl’s name.

The abbreviated meeting is nevertheless enough to fixate Balduin upon Margaret, and he immediately begins thinking about courting her. With considerable irony— irony that is entirely lost on him— he buys a spray of flowers from Liduschka the next afternoon, and heads off to pay the countess a visit. He never gets as far as handing over his little present, though, because while he’s still talking his way up to it, a courier arrives bearing a vastly more impressive arrangement from Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg; you might think of it as a silent, Teutonic version of the teddy bear scene in Better Off Dead. Balduin goes home to sulk, and so intent is he upon his brooding that he fails at first to notice that Liduschka has let herself into his apartment in his absence to channel her unrequited love for him into a small frenzy of cleaning and straightening up. She does get his attention after a little while, but he finally makes it inescapably clear to her that his romantic interest lies elsewhere. Liduschka trudges off to the nearest alley to do some sulking of her own at that point.

Reenter Scapinelli. He calls upon Balduin shortly after the younger man becomes aware of his wealthy, landed rival, and offers him a curious deal. Scapinelli says he’ll give Balduin 600,000 gold crowns in exchange for whatever one thing from the lad’s flat strikes his fancy, and produces a contract to that effect for Balduin to sign. At first, Balduin entertains a momentary fear that Scapinelli might covet his trusty saber, but he soon realizes that the fortune Scapinelli offers would more than suffice to outfit an army with such weapons. Balduin signs the contract, and Scapinelli astonishingly pours out several cubic feet of gold coins from the small velvet purse he digs out of his coat pocket. This, as you might guess, is when it finally dawns on Balduin that he’s dealing with no ordinary financier. Then Scapinelli claims his price. After looking the entire apartment up and down in a nearly lecherous manner, the wizard beckons Balduin over to the full-length mirror on his wall. It isn’t the mirror Scapinelli wants, however, but Balduin’s reflection, which he conjures out of the glass and leads off with him when he takes his leave of the now deeply alarmed student.

Having made his fateful bargain, Balduin wastes no time in exploiting it. First he makes a charitable donation to his school, creating a permanent endowment for the support of a hundred of his fellows. Then he buys a house commensurate with his new fortune. Finally, having situated himself so that he can pass plausibly enough for a Junker, he makes his move on Countess Margaret. His suit is remarkably successful, not least because of the poor grace with which Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg meets it, but Balduin overplays his hand when he sets up a clandestine liaison with Margaret at the city cemetery. Scapinelli, spying on the student’s activities, sees to it that the note with which Balduin made that arrangement finds its way into the jealous Liduschka’s hands, and she passes it along, in turn, to the baron. Meanwhile, Balduin discovers to his horror that his reflection is also following him about Prague, discreetly keeping tabs for who knows what insidious purpose.

Waldis-Schwarzenberg takes Liduschka’s news about the way you’d expect. He rides off at once to the university, finds Balduin, and strikes him across the face with his riding crop. Balduin may not have a “von” to stick in front of his undisclosed last name, but he still knows perfectly well the only appropriate response to an affront like that; he has one of the friends who witnessed the altercation issue the baron a challenge to a duel with heavy sabers. This comes as quite a shock to Waldis-Schwarzenberg, who has evidently not yet come around to thinking of Balduin as his social equal. Facing certain death at the hands of the finest young fencer in the city, he swallows his wounded pride and permits Count Schwarzenberg to plead with Balduin on his behalf. Balduin gives the old man his word that he’ll spare the baron’s life, but the student’s free-roaming reflection does not consider himself bound by his natural double’s promise. The reflection takes the field against Waldis-Schwarzenberg while Balduin is delayed by a broken carriage wheel, and leaves the baron in pieces. Then, having ruined Balduin’s honorable reputation, the reflection sets about systematically ruining the rest of his life.

A lot changed in the state of the cinematic art during the thirteen years that separate the two silent versions of The Student of Prague. Most noticeably, Henrick Galeen’s camera setups are much more varied than were Stellan Rye’s, and the second Student of Prague is consequently livelier and less stagebound than the first. Close-ups, long shots, tracking shots, and elaborate editing within the space of a single scene were not yet standard parts of cinematic grammar in 1913, and Rye made little use of them. Galeen does more with the camera, making his Student of Prague suspenseful and engaging in ways that the old version didn’t even attempt. The remake also benefits from a tighter script, and takes advantage of its significantly longer running time (nearly double that of the original) to delve deeper into the motivations of characters who were given little attention the first time around. Liduschka especially comes out ahead. Whereas before her behavior made very little sense, she now ends up being perhaps the most well-rounded character in the film, and in many respects the most sympathetic. And while I think I prefer John Gottowt’s performance as Scapinelli to that of Werner Krauss, it’s definitely an improvement to see the warlock wielding more of his malign magic. Similarly, it helps a lot, in a movie that makes such a big deal of its protagonist’s fencing skills, to see an actual sword-fight or two. True, the fencing scenes rely to a disappointing extent upon editing trickery, but even that can be given a positive spin in light of what a recent innovation editing trickery was in 1926.

The biggest improvement of all, however, is simply the replacement of Paul Wegener by Conrad Veidt in the title role. This is not to take anything away from Wegener, you understand. Wegener is the one who really deserves the “first horror star” title so often applied to Veidt by people whose only exposure to early German horror comes from the handful of films that have received wide circulation in the United States, and who thus forget how long that witch’s caldron had been bubbling before Cesare first shambled out of his box to murder at Dr. Caligari’s command. He was among the earliest exponents, years before Expressionism had been defined, of what would later become the central idea of the Expressionist school— that the surest route to cinematic artistry was to wed a strong dramatic narrative to film’s peerless effectiveness at rendering images of magic and the macabre. Veidt was in an altogether higher class of acting ability, though, the Boris Karloff to Wegener’s Lionel Atwill, and there is no clearer illustration of that point than a comparison between the two Balduins. Veidt’s acting is no less stylized, but it has an immediacy to it that Wegener’s lacks, and his sheer screen presence (albeit not his range or capacity for subtlety) puts him in the same league as the elder Lon Chaney. It doesn’t hurt, either, in the present context, that Veidt looks significantly younger than his actual age, even if he still looks nowhere near young enough to be a university student.

Unfortunately, the 1926 Student of Prague retains one major defect from its predecessor, the strange lack of urgency and escalation during the reflection’s final-act terror campaign against the original Balduin. You can see why the double’s actions would be both maddening and frightening if they were directed at you, but there’s something nebulous and unfocused about that part of the film that causes the tension to deflate at exactly the time when it should be increasing instead. Also, while Galeen makes admirable use of Balduin’s inability to cast a reflection, he ill-advisedly scales back the split-screen and double-exposure effects, subconsciously downplaying the doppelganger angle that differentiates this story from all the other soul-selling tales on the Faust model. The latter seems an especially serious misstep considering that 1926 was also the year in which F. W. Murnau weighed in with his direct Faust adaptation, a movie that can still plausibly claim to be the definitive film version. The definitive Student of Prague, meanwhile, perhaps has yet to be made.

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact