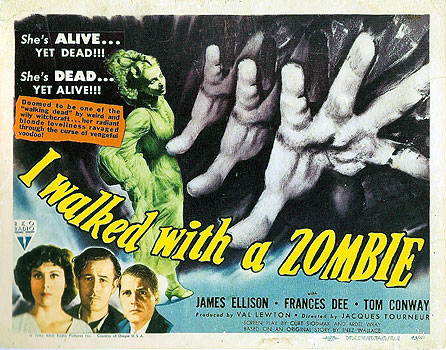

I Walked with a Zombie (1943) **

I Walked with a Zombie (1943) **

I wish I knew who said this, so that I could attribute it properly. Once upon a time, I encountered a review of Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie whose author contended that the movie’s main worth was its instructive value— “Watch this one to remind yourself how boring zombies were before George Romero came along.” I couldn’t agree more. I Walked with a Zombie has a couple of good ideas, one really good scene, and a single genuinely scary zombie, but on the whole, this is one tedious flick.

Any time a horror movie begins with a wistful, reflective voiceover from its female lead, it’s a safe bet that trouble is ahead. The woman is a nurse named Betsy Connell (Frances Dee), who has been hired by a planter on the island of Saint Sebastian to take care of his infirm wife. At first, Betsy is a bit put off by the idea of working in the Caribbean (is it possible that the place was not yet seen as the ultimate vacation destination in the early 40’s?), but she changes her tune when she sees her first South Seas sunset. Her employer, Paul Holland (Tom Conway, from Cat People and The Atomic Submarine), isn’t impressed, though, and he does his damnedest to spoil it for her by way of introducing himself. “Those flying fish aren’t leaping for joy,” he says, “they’re leaping in fear of the bigger fish that are trying to eat them. And that luminescence in the water is caused by the skeletons of millions of tiny animals. There’s no beauty here— only putrescence and death.” Even I’m not that big of a prick!

Holland’s plantation is a strange place. The various members of the family don’t get along very well, for one thing, and the bitter legacy of slavery hangs like a pall of misery over everything on the island in what I suppose was meant to be an atmospheric manner. Holland’s half-brother, Wesley Rand (The Undying Monster’s James Ellison), seems to have a particularly strong grudge against Betsy’s new employer, and all kinds of mysterious hints drop from the sky like seagull shit whenever he and Betsy are together. But it isn’t until Betsy encounters Jessica Holland (Christine Gordon) for the fist time that she has any real idea of what she has gotten herself into. One night, Betsy is awakened by the sound of crying emanating from the top of the big stone watchtower that incongruously dominates the Holland estate. When she goes to investigate, she finds that Jessica has followed her, and that Jessica’s ailment is not physical but mental. The woman is apparently unable to speak, her eyes are glassy and staring, and she generally looks like she died and was embalmed some years ago. Betsy’s screams bring Holland and Wesley running, and while Wesley bundles Jessica up and sends her back to bed, Holland has unnecessarily caustic and condescending words with Betsy.

So who was up there crying, you ask? That would be Alma (Theresa Harris, another Cat People graduate, who had encountered Caribbean black magic once before in Drums o’ Voodoo), one of Holland’s domestics. One of her relatives was giving birth that night, and apparently on Saint Sebastian, it is traditional to mourn births and rejoice at funerals— more of that bitter-legacy-of-slavery business I mentioned before. It is Alma who first hints at the idea that Jessica’s problem is that she has been turned into a zombie, an idea that comes to take a curiously strong hold on Betsy’s mind. Certainly nothing that island physician Dr. Maxwell (James Bell of The Leopard Man) or Wesley’s mother (The Ghost Ship’s Edith Barrett), who works as his assistant, have tried has had any effect on Jessica’s condition (which supposedly was brought on by a severe fever), so anything they have to say about what’s causing it should perhaps be viewed with a skeptical eye.

But there’s definitely more going on here than anyone is willing to talk about, and the stronger Betsy’s new and utterly implausible attraction to Holland grows, the more determined she becomes to get to the bottom of it all. You see, Betsy’s love for her complete bastard employer makes her want to restore Jessica to him, since she is unable to express that love through the usual channels. And eventually, Betsy gets it into her head that the local houngan, or voodoo priest, might be able to succeed where Western medicine failed. To that end, she has Alma give her a crash course in the proper way to come in supplication before a voodoo witch doctor, and then sets off with Jessica to the houngan’s camp. This is I Walked with a Zombie’s one really good scene. For a few brief minutes, Tourneur finds just the right touch with his otherwise cloying and heavy-handed atmospherics (it’s funny that this should be such a conspicuous failing throughout I Walked with a Zombie, given that atmosphere was usually one of Tourneur’s strong points), and the women’s midnight trip through the maze of the cane fields, culminating in our first look at the zombie Carrefour (Darby Jones, from Queen of the Amazons and Zamba), is right up there with the swimming pool scene in Cat People in terms of tension and foreboding. And the revelation that greets Betsy when she brings Jessica before the witch doctor— that Wesley’s mother isn’t just Dr. Maxwell’s assistant, but the houngan’s as well— is a truly unexpected twist. Looks like Mrs. Rand knew what she was talking about when she told Betsy that the houngan’s powers lay only in the minds of the islanders, huh?

But even so, her dismissal of Betsy and Jessica seems awfully suspicious, especially in light of the fact that the few quick tests that the houngan’s henchmen administer to Jessica come up positive for zombification. You think Mrs. Rand might know more than she’s telling about how Jessica got to be the way she is? And do you think there may be something to the islanders’ songs whose lyrics have it that Jessica was taken ill immediately after her husband discovered her having an affair with Wesley? That would certainly explain why Wesley seems so much more upset over Jessica’s condition than his brother, and if Mrs. Rand was involved in some direct way, it might also explain why neither one of her “boys” exhibits any apparent affection for her. With her moonlighting as the houngan’s sidekick, she’d also be ideally placed to lay a zombie curse on the woman who had driven a wedge through the center of her family. But if you’re looking for a conclusive answer to any of these questions, you’re looking in the wrong place. I Walked with a Zombie is a Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur movie, after all. Far be it from either of those guys to give you a straight answer about anything!

A lot of people consider I Walked with a Zombie second only to Cat People among RKO’s Lewton-produced thrillers from the early-to-mid 1940’s. The main basis for all this praise seems to be the “poetry” of the film, with its juxtaposition of family dysfunction and black magic against the scenic beauty of the idyllic West Indies setting. Call me boor and a knuckle-dragger, but I frankly couldn’t care less about such things. This is a voodoo movie, damn it! If I want poetry, I’ll watch Swedish art films, and the fact that I don’t watch Swedish art films should tell you something about the extent to which I watch movies for their poetry. And that goes double for movies that have the word “zombie” in the title. Obviously, I don’t expect something like Dawn of the Dead from an early-40’s zombie/voodoo flick, but this kind of maudlin melodrama is the last thing I want to see. The fact that scattered bits and pieces of I Walked with a Zombie actually do work just makes the parts that don’t that much more frustrating.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact