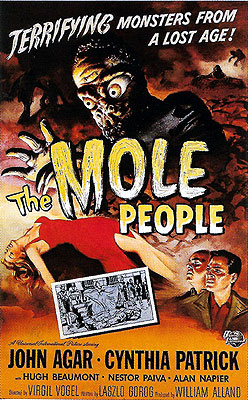

The Mole People (1956) **

The Mole People (1956) **

Most of the Universal Studios horror/monster flicks from the 1950’s are a bit on the tepid side, and The Mole People is no exception. But there’s one point that just about all of them have in their favor— the studio was willing to spend a butt-load of money (by the standards of the day, at least) on the monsters. And here, once again, The Mole People is no exception. On the other hand, it also has both John Agar and that drab, flat, lifeless documentary-style direction characteristic of so many 50’s films dragging it down.

Oh, and did I mention it starts off with a lecture? Before we get to see the movie, we have to sit through nearly ten minutes of some guy who may or may not really be a professor of English at UCLA reading (from cue cards— and man is it ever obvious) a boring-ass speech about the various fanciful ideas that people over the ages have entertained regarding what may lie deep below the Earth’s surface. We get a guided tour through the underworlds of Greek and Mesopotamian mythology, a nod is given in the direction of Dante’s Inferno (is it really possible that an English professor would call Italy’s most famous poet “the great Danty”?), and even some of the more recent crackpot hollow-Earth theories are trotted out for our edification. Then, in a ham-fisted effort to provide a smooth segue into the film proper, Professor Nutsack admonishes us that The Mole People may be fiction, but it is also much more than that— a fable with lots of important things to tell us about how we should be leading our lives. I have but one thing to say in response to this introduction: “Man, fuck you guys!” Seriously, did the studio suits at Universal really have so little respect for their audience’s intelligence that they thought we’d need to be told explicitly— by an imposter university professor no less!— that this wasn’t going to be a true story, and that we couldn’t really dig down into the ground someplace in central Asia and find a lost race of albinos? Do we really look that stupid? And furthermore, do we look like such pathetic low-lives that we need moral instruction from a two-bit monster flick— and one with a name like The Mole People at that? Like I said, fuck you guys.

Anyway, when the real movie starts, we are introduced to a team of archaeologists on a dig in “Asia.” (Again I detect a hint of condescension— like we’re all such dumb-asses we wouldn’t know where, say, Iraq was!) The boss-man on the expedition is Dr. Roger Bentley (Agar, from Revenge of the Creature and The Brain from Planet Arous), an expert on ancient Sumer. It’s never made clear what he and his colleagues, Dr. Jud Bellamin (Hugh Beaumont, Ward Cleaver himself), Dr. Etienne LaFarge (Nestor Paiva, of Creature from the Black Lagoon and They Saved Hitler’s Brain), and Dr. Paul Stuart (Phil Chambers), are looking for, but what they find is the ruin of a hitherto-unsuspected Sumerian temple halfway up the slope of a steep, treacherous mountain. (You know, this “Sumerian” temple looks a hell of a lot more like something out of Hellenistic Persia to me...) While Dr. Stuart is exploring part of the ruin, the ground gives way beneath his feet, and he falls hundreds of feet down into a huge subterranean cavern that seems to account for most of the mountain’s internal volume. A rescue attempt by Bentley, Bellamin, and LaFarge is obviously hopeless, as no one could possibly survive a drop like that. More importantly, the fruitless effort to save Stuart ends up causing a rockslide that traps all three remaining scientists underground.

While Bentley and company are busy searching for a way out, they stumble upon something truly incredible— an entire Sumerian city laid out in the largest section of the cavern. This central gallery is lit by some sort of luminescent chemical in the rocks, so that, while it’s still pretty dark, there’s at least enough light for a person to get by. As exciting as this discovery is, the scientists are all very tired— they’ve been wandering the caves for more than fifteen hours by this point— and they understandably decide to save the investigation of the city for later, after a good, long nap. It’s just not their day, though. The three men have scarcely drifted off to sleep when a bunch of strange creatures with huge clawed hands dig out of the ground beside them, throw cloth sacks over their heads, and drag them off to wherever it is the things came from.

It turns out that city is still inhabited by the descendants of an ancient king and his retinue, who fled to the mountain to escape from the cataclysmic flood described in the epic of Gilgamesh. A subsequent earthquake sank the bulk of their settlement below the surface, and they have lived there in secret— and in ignorance of the world above— ever since. The creatures that captured Bentley, Bellamin, and LaFarge are what the Sumerians call “the Beasts of the Darkness,” the Mole People of the title, who are used for slave labor by the Sumerians. The Mole People grow and harvest the mushrooms that serve as the Sumerians’ principal foodstuff, an arrangement that is difficult to understand, given that it was clearly imposed on the creatures against their will by the numerically far inferior and physically far weaker humans. In fact, it seems that just about every man in the city is employed keeping the subhuman slaves in line, whether by overseeing their labor directly, by serving as soldiers to deter their rising up against their masters, or by manufacturing the weapons and armor used by those soldiers. Meanwhile, the women seem to sit around all day playing lutes. All of this becomes apparent shortly after the scientists are taken to meet King Sharu (Arthur D. Gilmour), ruler of the city. The king and his high priest, Elinu (Alan Napier, from The Premature Burial and The Island of Lost Women), initially decide that the scientists must be killed, on the grounds that, as outsiders, they can only be some sort of evil spirits, and LaFarge actually is killed (but by one of the Mole People, rather than by Sharu’s soldiers— this will be important later) when he tries to run away. But when the subterranean honchos get a look at Bentley’s flashlight (the Sumerians have evolved extremely sensitive eyes to cope with the low light levels in their cavern, making a flashlight a very effective weapon against them), they change their minds. The king’s reconsidered opinion is that the flashlight contains “the Fire of Ishtar,” and that Bentley and company must thus be some kind of divine emissaries. Over the objections of Elinu, the king accepts the men from upstairs as his honored guests, even giving Bentley one of his own slaves, a pretty girl named Adad (Cynthia Patrick), as a gift.

This is where things start to turn ugly. Adad is a “Marked One.” That is to say, she was atavistically born with the pigmented skin, hair, and eyes of her ancient ancestors. The Marked Ones are second-class citizens down here, considered nearly as subhuman as the Mole People, and like them fit only for a lifetime of servitude. The whole slave-society business really begins to get on Bentley’s nerves after the first day or so, and he soon begins making a big pest of himself, interfering with the system every chance he gets. The offense he takes at the way Adad is treated is fully understandable, as is his disgust at the Sumerians’ practice of sacrificing their surplus population to Ishtar. (They do this by sending them, naked [and note that it’s always pretty girls who get singled out for sacrifice here], into a locked chamber in the temple. After a few hours in that chamber, the victims are burned to a crisp— this will also be important later.) More surprisingly, Bentley even intervenes on behalf of the Mole People, stepping in to prevent them from being mistreated while they harvest the mushrooms. Now nobody likes to have some bunch of outsiders come along and tell them their way of doing things is fucked up, so it isn’t altogether surprising that Elinu quickly starts plotting against Bentley. He figures that if he can get the scientists’ flashlight, he will then have the power of Ishtar’s Fire, and he’ll be able to do entirely as he pleases. When one of the temple guards finds LaFarge’s body in one of the less frequently used tunnels, Elinu battens onto it as proof of Bentley and Bellamin’s mortality, and he gleefully goes to make his case to King Sharu. When the king sees the body, he comes around to Elinu’s way of thinking, and orders the scientists killed by the same means as the sacrifices— baked to death by the Fire of Ishtar.

Meanwhile, rumors have been circulating to the effect that the Mole People are plotting revolution. They’ve already instituted a work slowdown at the mushroom harvest, forcing the king to send even more sacrifices to Ishtar than usual. When Elinu’s soldiers come to collect Bentley and Bellamin, Adad runs off to the mushroom plantation, and somehow galvanizes the disgruntled creatures into action. They storm the city, slaughtering the Sumerians as they go, until they reach the temple itself. Elinu tries to ward them off with Bentley’s flashlight, but gets a nasty shock when he discovers that the batteries are dead. Finally, Adad gets a few of the Mole People to break down the door to the chamber that holds the Fire of Ishtar, hoping to rescue Bentley and Bellamin. But as it happens, the scientists need no rescue at all. You see, some things that are very bad for albinos don’t bother those of us with melanin in our skins one little bit...

Cool idea, inept execution. The unimaginative directorial style works against the movie at every turn. The script asks a lot of our disbelief-suspenders, and doesn’t give them much to work with. The acting is particularly shabby, and though Agar doesn’t seem as bored here as he did in Revenge of the Creature, he still basically sleepwalks through his role. Hugh Beaumont and Nestor Paiva are both mostly forgettable, and Cynthia Patrick is so fucking awful that it’s easy to understand why her career flamed out so quickly— she made three low-budget B-movies in 1956, and then dropped out of sight forever. Finally, the cloying self-righteousness of the Americans-against-the-Slave-State theme becomes acutely offensive very fast, not the sort of thing you want to see in a movie that starts out by insulting the viewer’s intelligence. On the other hand, we all know why we really watch these movies— we want to see cool rubber-suit monsters. And The Mole People has a veritable army of them. It’s not enough to make it a good film, but it’s enough to make it suitable entertainment for an otherwise unoccupied Saturday afternoon— which, after all, is what it was really designed to be in the first place.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact