Bluebeard (1944) **½

Bluebeard (1944) **½

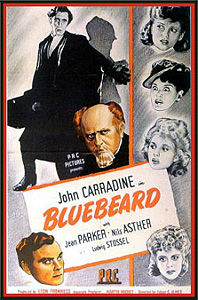

Perhaps I should start by heading off a potential misconception. Between the title and the tag-line (“To love him meant DEATH!”), you’d probably expect this mid-40’s offering from Edgar G. Ulmer (his only horror film for PRC, so far as I have been able to determine) to be an adaptation of the French folktale about the guy who murders his succession of wives and then collects their severed heads in a secret, locked room in his house. In point of fact, this Bluebeard has only slightly more to do with that one than Ulmer’s The Black Cat had to do with Poe’s. Instead, what we have here is a fairly typical pre-slasher mad killer movie, livened up a bit by one of John Carradine’s best non-mad scientist performances and an attention to detail in the production design which hardly seems possible coming from the lowest of the low on Poverty Row.

There’s a murderer stalking Paris, a murderer who specializes in pretty, young women. Apparently because he is both a slayer of women and presumably French, the press immediately dubs him “Bluebeard,” and the name sticks. The killer’s activities have most Parisian females jumping at their own shadows, but not a young fashion designer named Lucille (Jean Parker, from One Body Too Many and Dead Man’s Eyes). Though her friends, Bebette (Patty McCarty) and Constance (Carrie Devan), have taken to avoiding and fleeing from every man who makes eye contact with them, Lucille goes right about her business as if Bluebeard were no more real than his folkloric namesake. Consequently, when she and the other girls meet up with Gaston Morrell, the puppeteer (John Carradine, from The Face of Marble and The Invisible Man’s Revenge), on the street one evening, Lucille strikes up such a charming conversation that Morrell says he’ll put on a performance in the park tomorrow, just so that she can see him in action.

If you’re expecting something along the lines of Punch and Judy, you could scarcely be more wrong— would you believe Gaston and his two assistants, Renee (Sonia Sorel) and Deschamps (Henry Kolker, of The Black Room and Mad Love), put on a marionette version of Faust?! And as a full-fledged opera, no less? After the show, Morrell leaves his partners to deal with the oncoming flood of backstage curiosity seekers, and goes out into the crowd to collect donations. While he’s at it, he also makes a point of chatting up Lucille again, and when he hears what she does for a living, he asks if she’d consider making him some new costumes for his puppets. He’s already got the necessary designs worked out (the multitalented Morrell is not only a singing puppeteer, but evidently a clothing designer, a sculptor, and a painter as well— he makes his own marionettes in the image of people he knows, working from preliminary portraits, which he then sells to generate the bulk of his income), so it would really take very little of Lucille’s time. Lucille says she’d be honored, and even offers to sit for a portrait so that Gaston can make a new puppet to dress in her wares. The rather startled and agitated way in which Morrell turns her down is the first hint that this guy is perhaps not so harmless as he seems… well, apart from the fact that he’s played by John Carradine.

That evening, back at the flat they share, Renee pitches a fit over the way she saw Gaston talking to Lucille. Apparently this is far from the first time a pretty girl from the audience has caught the puppeteer’s eye, and apparently each time it’s happened before, Gaston has given Renee the boot and taken the new girl on in her place. He paints her picture, carves a puppet in her likeness, and puts on a show or two with her doing all the female roles. A few days later, however, he always comes back to Renee. Not this time, though. Renee has finally had enough of Gaston’s serial dalliances, and she isn’t going to stand around waiting for him to get bored with Lucille. But while she and Morrell are having it out, Renee makes a mental connection she never had before. It isn’t just that Gaston’s floozies no longer hang around the puppet theater after he’s finished with them. Rather, Renee has never seen a single one of them again, even by happenstance, after the fling has run its course. Suddenly Renee thinks of all those bodies the police have been pulling out of the Seine, and she understands what’s really going on. And that, of course, means that Gaston will have to kill her.

Speaking of the police, let’s have a look at what they’re doing to catch Bluebeard. Sadly, it seems as though the answer is “not a whole lot.” Inspector Jacques Lefevre (Night Monster’s Nils Asther) hasn’t a single clue worthy of the name, and he’s just about at his wits’ end. But then one of his men draws an assignment standing guard over some duke’s private art exhibition, and he notices that one of the canvases on display unmistakably depicts one of Bluebeard’s victims. The duke identifies the dealer who sold him the painting in question as Jean Lamarte (Ludwig Stössel, of From the Earth to the Moon and House of Dracula), giving Lefevre a real, live lead to follow up at last. Lamarte, in case you couldn’t figure this out, is the dealer through whom Gaston sells all of his paintings. He’s also the homicidal artist’s landlord, and he has used the latter position to force Morrell to keep painting— which in turn means that he keeps killing, as he invariably feels compelled to murder every young woman who sits for his portraits. Lamarte seems to know the end result of the pressure to create which he puts on Gaston, but since the painter is his big meal ticket, he doesn’t much care; consequently, the art dealer blows smoke up Lefevre’s ass when he comes around asking if Lamarte has any idea how one might get in touch with the man who painted the picture of the dead girl.

There remains one last angle to play in the effort to make the clues derived from the painting bear fruit, however. Lefevre’s girlfriend, Francine (Return of the Ape Man’s Teala Loring)— who happens also to be Lucille’s little sister— is a cop herself, and the two of them together devise what is either a truly brilliant scheme to trap the killer or an idea so bad that the English language (or the French either) has no words to do justice to its badness. Lefevre’s boss, Inspector Renard (George Pembroke, from Black Dragons and The Invisible Ghost), will pose as a visiting South American millionaire who is friends with the duke, and who wants someone to paint a portrait of his daughter— really Francine, of course. Renard will go to Lamarte, saying that he was recommended by the duke, and asking specifically to be put in touch with the suspect artist. Of course, a risky trap like this one can just as easily snare the person laying it, and meanwhile, the sudden disappearance of Renee means that Gaston has plenty of time on his hands to spend with Lucille, putting her in just as much danger as Francine.

I have no figures to back me up on this point, admittedly, but I feel pretty confident in saying that Bluebeard was almost certainly the most expensive horror movie PRC ever released (although this should not be taken to imply that Bluebeard was especially well-funded in absolute terms). It’s the only one I’ve seen that was a period piece, for one thing, and while John Carradine was hardly discriminating when it came to accepting a role, he was a rather bigger name than PRC regulars George Zucco and J. Carrol Naish, and he didn’t have a morphine habit like Lugosi’s to keep his asking price down in the cellar. Furthermore, director Edgar G. Ulmer had some name recognition going for him, too. The most noticeable indicator of an unusually big budget, however, are the sets and matte paintings, which are far better executed and more detailed than anything else I’ve seen from the studio— indeed, I’ve encountered worse in both departments in contemporary films from 20th Century Fox and even Universal! Truth be told, I expect that last part is mostly the result of Ulmer being the one with his butt in the director’s chair. Having already worked on such distinctive-looking movies as The Black Cat and The Golem, he had amply demonstrated a knack for eye-catching production design. What it all means in aggregate is that, for once, PRC have put together something that demands to be taken seriously as an actual movie.

For my purposes, that’s something of a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it comes as a welcome surprise to see that the story isn’t utterly ridiculous even despite its typically PRC-ish circuitousness, and John Carradine does an extremely good job with the unusual (for him at least) role of a villain who wants very, very badly not to be evil anymore. It’s also fun to see how Ulmer consistently makes the necessity for frequent resort to matte paintings work for rather than against him, taking what must surely have been a simple cost-controlling measure and making it look like deliberate stylization instead. But at the same time, there is an awkward self-consciousness about Bluebeard, a sense that everyone involved spent the full length of the shooting schedule keeping their fingers crossed and uttering silent prayers that they wouldn’t screw up this unique opportunity to make the most debased production house in Hollywood look good. Bluebeard plays as though its creators found its unaccustomed seriousness intimidating, and it seems as though they let themselves be cowed by it to some extent, rather than rising to the occasion. As the most ambitious of the PRC horror films, it definitely merits a look, but it isn’t quite the movie that it could have been.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact