The Face of Marble (1946) -**½

The Face of Marble (1946) -**½

This, so far as I know, was the last of Monogram’s 1940’s horror movies, and perhaps surprisingly, it’s also one of the more enjoyable ones that I’ve seen. The Face of Marble is, of course, immensely stupid, while one gets the feeling watching it that the folks in charge at the studio knew the game was almost up for this sort of film, and tried to take all the horror ideas they’d ever had which hadn’t yet found their way into a finished movie and roll them all together into one flick. Mad science, voodoo, ghosts, zombies— it’s all right here, along with (astoundingly) a spectral great Dane that walks through walls. But the most frightening thing about The Face of Marble is what confronts you in the final frames of the opening credits: “Directed by William Beaudine!”

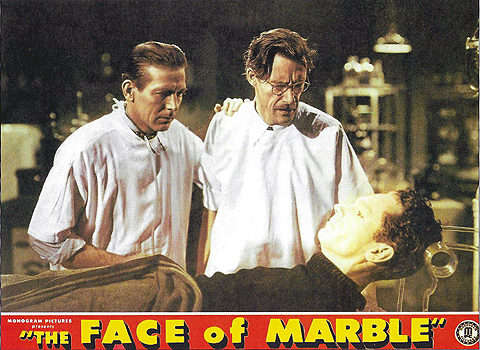

We last saw William Beaudine, you may recall, at the very end of his career, in the context of his stupefying vampire western Billy the Kid vs. Dracula. That, believe it or not, appears to have been one of his more professional efforts. This time around, the slapdash don’t-give-a-fuck quality that led him to be known as One-Shot Beaudine is in full effect. At least we’ve got John Carradine (from Revenge of the Zombies and The Unearthly) on our side. Carradine plays a medical researcher named Charles Randolph, who has recently moved to an isolated mansion somewhere on the Atlantic coast in search of the privacy he needs to complete his latest project. With the help of another doctor, one David Cochran (Robert Shayne, of The Neanderthal Man and How to Make a Monster), he is (as per the norm in the 1940’s) working to develop a way to restore life to dead tissue. Randolph isn’t quite your usual mad scientist though. Whereas most of that lot want to build zombies for Hitler or start up their own master race of synthetic supermen or maybe just put together an indestructible mosaic monster simply for the hell of it, Randolph’s research has a legitimate medical purpose— he’s merely looking for the means to restore the recently dead (as in, a couple of hours or less) to life, much the way real-life doctors sometimes can today. Nevertheless, by 40’s standards, this is some pretty creepy stuff, and you can scarcely blame the doctor for wanting to keep a lid on it until he’s achieved enough unequivocal success that he’s ready to go public. Our introduction to Randolph’s work comes late one night when he and Cochran bring into their lab the body of a drowned sailor whose ship seems to have been lost in the storm raging just off the coast. Randolph’s butler, Shadrach (The Monster and the Ape’s Willie Best), sees the two men sneaking the corpse in, though, and mentions the strange goings on to his boss’s wife, Elaine (Claudia Drake). Puzzled by Shadrach’s story, Elaine heads downstairs to the lab, where she interrupts the two scientists just as they were about to activate the usual array of extravagant electrical equipment. Cochran shoos her off to bed before she gets too good a look around, but Elaine knows a dead body when she sees it, and she gets it into her head that her husband is up to no good.

At first glance, you might say she has something there. When the current hits the dead man, he does indeed twitch his way back to something resembling life, but he’s scarcely in the sort of condition Randolph and Cochran intended. For one thing, there’s his face— colorless, expressionless, immovable. (“But that face!” says Dr. Cochran, “It’s a face of marble!” I hope you enjoyed that rather unsubtle gesture in the direction of the movie’s title— we shan’t be seeing it again until the final act.) Worse still, it looks as though anyone brought back to life by means of Randolph’s new process will arise as a homicidal zombie; only the sudden short-circuiting of the machine’s main power supply saves the scientists from their creation’s attack.

Meanwhile, the voodoo element enters the plot via the Randolphs’ maid, Maria (Rosa Rey). The doctor picked Maria up overseas, at about the same time that he married Elaine. Maria is extremely devoted to her mistress, and never hesitates to practice her strange island magic on the younger woman’s behalf. Just lately, Maria has convinced herself that Elaine has fallen in love with Dr. Cochran— who, to be fair, really does seem to be a more logical match for her than the older, more driven Dr. Randolph— and as we are soon to learn, she has set herself to the task of bringing them together, consequences be damned. The first indication of this comes on the morning after the failed experiment, when Cochran finds a handmade voodoo charm depicting some love goddess or other in his room. Perplexed, he asks Randolph if he has any idea what it is; he does, and the older doctor explains that someone (hint, hint) wants Cochran to fall in love. Cochran then protests that he’s already in love— with a girl from his hometown named Linda Sinclair. The subject is then dropped in favor of Cochran’s worries regarding what happened last night. He fears that someone will be able to trace the dead sailor (whom they returned to the beach after the power went out in the lab) back to them, and perhaps conclude that it was he and Randolph who killed the man in the first place.

Though the brief report on the subject that he finds in the morning newspaper convinces him that he and his assistant have nothing to fear, Randolph might do well to take Cochran’s concerns more seriously. While the doctors are in town buying replacement parts for their ruined lab equipment, a police detective called Inspector Peter Norton (Thomas E. Jackson, from Doctor X and Valley of the Zombies) stops by to talk to Randolph. Although he may tell Elaine that it’s just a social call (he and her husband are old friends), the entry of a cop into the story can scarcely be merely a coincidence. And indeed, when he gets in touch with Randolph later, it turns out that Norton has found himself in the difficult position of having to investigate his old pal for murder. True to Cochran’s fears, the medical examiner has determined that the cause of death was electric shock, which makes the doctor’s shopping trip the morning afterward look awfully suspicious.

Now if you’re at all like me, you’ve probably spent the entire time that you’ve been reading this saying, “Yeah, but what about the great Dane? You said we’d be seeing a ghostly great Dane!” Well the dog in question is named Brutus, and he is Elaine’s inseparable companion. He’s also the next experimental subject Randolph tries his Resurrectomatic on. And yes, my ever-perceptive readers, that means Randolph has to kill the poor critter while his wife is asleep. It’s your textbook movie-scientist hubris, really— Charles is so certain his process will work this time that it never even occurs to him to imagine Elaine’s reaction in the event that anything should go wrong. What goes wrong is that Brutus comes back to life just as murderous as the sailor had (though it seems that there was no money in the budget for a Muzzle of Marble), and with the ability to pass through solid matter when it suits him to do so. Randolph and Cochran should just count themselves lucky that Brutus apparently likes mutton more than he likes human flesh, for the ghost-dog immediately takes his leave of the doctor’s mansion to begin a new career as the great nemesis of the local shepherds. And need I even bother to tell you that Elaine doesn’t find her husband’s story that he took Brutus to the vet for distemper treatments before she woke up terribly convincing? No. I didn’t think so. Just about the only good that comes of this situation is that it jolts Dr. Randolph into rethinking the value of his research.

We’ve still got one more angle to work into the plot here, though. The day after the Brutus incident is Cochran’s birthday, and as a special surprise, Randolph has arranged for Linda Sinclair (Maris Wrixon, of The Ape and White Pongo) to come visit him at the house. This gets Maria really worked up. After all, Linda would seem to present an almost insurmountable obstacle to her efforts to hook Elaine up with Dr. Cochran. With that in mind, the scheming maid begins looking for ways to get rid of the new girl. First she somehow arranges for the undead Brutus to attack Linda in her bedroom one night. Then when that fails, she whips up some kind of voodoo nerve gas potion, which she plants in Linda’s room for activation the following night. But Maria has miscalculated. Unbeknownst to her, the previous night’s visit from Brutus has scared Linda into trading rooms with her hostess. Thus it is Elaine who is sleeping in that room when Maria’s lethally effective gas-bomb goes off. Randolph practically has a nervous breakdown in response to his wife’s death, and Cochran feels so distraught on his partner’s behalf that he rather recklessly uses the Resurrectomatic on Elaine. He’s been thinking, you see, and it is his opinion that a quick does of muscle relaxants administered right when the Face of Marble appears should counteract the resuscitation process’s side effects. As it is, though, he’s only half right…

Unless you lived through it yourself (which I most assuredly did not), it’s difficult to imagine that there was ever a time when movies as mind-bendingly dumb as The Face of Marble were reckoned respectable enough to be given theatrical release. The economics of direct-to-video are such that virtually anything can get made and find some kind of distribution, but just try to picture something like The Face of Marble showing up in even the sleaziest of theaters today. And yet even with the old Hollywood studio system fully in place, companies like Monogram somehow managed to survive on the strength of such utterly shameless crap. I know I’ve raised the issue before in other reviews, but I still find myself in awe whenever I sit down to watch a minor-studio B-picture from the 40’s, and am forced to confront the reality that actors like John Carradine and directors like William Beaudine were able to earn quite a comfortable living making the things.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact