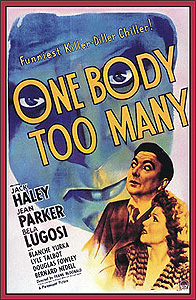

One Body Too Many (1944) **½

One Body Too Many (1944) **½

Would you look at that… It turns out there really is a first time for everything. Most of the time, I treat gearing up to watch a 40’s horror comedy about the same way that the gladiators of ancient Rome treated preparing for their next turn in the arena. As I’ve learned from hard, painful experience, the typical horror comedy from those days is nothing but slapstick and screaming, scene after scene after scene. Maybe, if you’re really lucky, they’ll do that hoary old gag with the guy in the gorilla suit taking the place of whomever was walking behind the main character down the secret passage, too— ‘cause that one never stops being funny, no sir! Anyway, I figured One Body Too Many would be no different, and for a few minutes there it looked like I was right. But then a funny thing happened— by which I mean that a funny thing happened! Then another one came along not too much later, and that second funny thing must have brought a few of its friends with it, because this film did a decent job keeping me fairly amused all the way through to the end. I’m not saying One Body Too Many is laugh-out-loud funny, mind you, but it kept me smiling and even got a chuckle or two out of me, and that’s a hell of a lot more than I would have considered possible going in.

Now the first thing we need for any spooky old house comedy (well, after a spooky old house, I mean) is a coward who’ll have to spend the night there due to some ridiculous misunderstanding. One Body Too Many’s is life insurance salesman Albert Tuttle (Jack Haley, who had much the same gig in Scared Stiff the next year), who about a month ago landed an appointment to sell a $200,000 policy to eccentric millionaire Cyrus J. Rutherford. Rutherford is obsessed with astrology, and Tuttle got the deal by telling the tycoon that he was born under the same star sign as him. The time of the appointment, too, was set on astrological grounds, and it is for that reason that the salesman has seen no reason to call up his would-be client to reconfirm their date. That’s mistake number one on Tuttle’s part.

Rutherford, unbeknownst to Tuttle, is no longer in the market for life insurance, because Rutherford, unbeknownst to Tuttle, has just keeled over dead. His will, as is pretty much standard in movies like this, is a peculiar document, every bit as eccentric as the man who ordered it drawn up. First, it divides the $8,000,000 estate up into drastically unequal shares— the largest at $500,000, the smallest at $1.50 (“to pay for the taxi from the station”)— among a total of eleven heirs. Second, it stipulates that Rutherford’s body is to be placed within a glass-topped coffin in a glass-topped vault on the roof of his mansion, so that the stars he considered so important during his life may continue to shine on him now that he is dead. What’s more, the burial clause goes on to state that if the deceased’s wishes are disregarded, then the distribution of the bequests will be reversed, with the largest share going to the heir previously earmarked for the $1.50 and vice-versa, and because the will proper shall remain sealed until after the burial, none of the heirs can be certain whether they will lose or gain by countermanding the dead man’s orders. Finally, every one of the assembled heirs must henceforth remain in the mansion or on its grounds until the vault is completed and its owner interred, probably a few days from now; the penalty for leaving is the forfeiture of whatever legacy Rutherford’s will grants. You get the feeling Rutherford concocted this whole scheme expressly to give his heirs a hard time?

As for the heirs, I say we let Rutherford speak for himself on the subject:

My sister Estelle (Fay Helm, from Night Monster and Captive Wild Woman), who 20 years ago disobeyed my wishes by marrying a nincompoop named, I believe, Kenneth (Lucien Littlefield, also of Scared Stiff), and whom I’ve had the pleasure of not seeing since. And niece, Margaret (Maxine Fife), whom I have never seen— which is probably just as well. My nephew, James Davis (Torture Ship’s Lyle Talbott, who went on to play the general in Plan 9 from Outer Space)— I last saw him when he was an impertinent youth of twenty. I do not like impertinence, and I did not like James. My niece, Carol Dunlap (Jean Parker, of Bluebeard and Dead Man’s Eyes), although I despised her father, turned out to have somewhat better intelligence and a less selfish interest in her old uncle than others in the family. And the last of my living relatives, nephew Henry Rutherford (Douglas Fowley, from Mighty Joe Young and Cat-Women of the Moon) and his wife, Mona (Dorothy Granger). Henry at least has the virtue of bearing the Rutherford name, and he was a fairly good investment counselor, honest as far as I could find out; Mona wears too much makeup, and she seems to have waited with undue impatience for my demise. My faithful butler, Murkill (Bela Lugosi), who for twenty years padded the household bills, and Matthews (Cry of the Werewolf’s Blanche Yurka), who kept house for me in a haphazard sort of way. Professor Hilton (William Edmunds, from House of Frankenstein and The Beast with Five Fingers), to whom I owe my understanding of the secrets of the heavens. And my lawyer, Morton Gelman (Bernard Nedell), whom I trust implicitly as far as I can throw an elephant. |

All in all, I’d say that sheds some light on the old man’s reasons for making the terms of his will such a colossal pain in the ass.

Gelman, for his part, has well anticipated the contentiousness and backstabbing he can expect from his client’s beneficiaries, and so in an effort to cut down on the opportunities for foul play, he has hired a private detective to stand guard over Rutherford’s body until the completion of the vault. No sooner has the detective strode up to the front stoop of the Rutherford mansion, however, than somebody cold-cocks him and drags him off. Thus when Albert Tuttle arrives on the scene, everybody initially takes him to be the hired guard. Carol comes to him with a threatening note she found in her luggage, on which basis she’s certain that somebody in the house plans on using murder to redistribute Uncle Cyrus’s largesse. Mona hits on him. And Gelman locks him in the parlor with the coffin— only then does Tuttle figure out that Rutherford is dead, and only then does he grasp the extent of the twofold screw-up he’s wandered into. Tuttle flips, but Carol manages to charm him into sticking around to take the place of the missing detective— nothing like appealing to a coward’s wobbly sense of manly honor, eh?

So is there anybody out there who really needs me to tell them that Tuttle is about to get caught up in an absurdly complex caper involving assault, body-snatching, and multiple murder? Of course not. The first two parts of that triad of crime come into play not long after Tuttle takes his seat in the locked parlor. The lights briefly go out, and while Tuttle is groping around for a candle or a flashlight, somebody whacks him on the head and runs off with Cyrus Rutherford. More importantly, although the dead man turns up soon enough in a hidden compartment in the very room from which he was apparently shanghaied, we will later hear the conspirators behind the attack on Tuttle remarking that that was not where they hid him. Obviously there’s more than one set of heirs operating on the assumption that they’ve been earmarked for a dinky bequest. Meanwhile, Murkill comments to Matthews out in the kitchen that “There are too many rats in this house,” and picks up a vial of poison along with the silver coffee service on his way out to the library, where most of the others have gathered. He’ll spend the rest of the film trying without success to get the guests to drink a cup of this suspicious coffee. Then people start dropping dead— beginning with Morton Gelman— and those who remain alive come to understand at last just how serious the situation is. The situations Tuttle falls into while trying to expose the criminals, on the other hand… well, those are a bit less serious, you might say.

What sets One Body Too Many (and incidentally, there are at least two bodies too many, if you want to be picky about it) on a plane above its contemporaries in the horror-comedy field is its refusal to rely too much on the juvenile antics typical of the era. To be sure, it has its share of “see— Tuttle’s a coward, so it’s funny” moments, but the emphasis is primarily on a more sophisticated sort of humor. The diatribe against his heirs which makes up most of the preamble to Cyrus Rutherford’s will— and the barely concealed relish with which Gelman reads it until he comes to the part about himself— is an excellent example, but it is far from the only one. There’s also an effective situational gag in which a chain of increasingly absurd mishaps culminates in Tuttle being caught hiding, naked, in a clothes hamper in Carol’s room, clutching a handful of black kittens; Carol, as you might imagine, refuses to speak to him for several scenes after that. The funniest thing of all, though, is the running joke about the coffee. Bela Lugosi displays here a capacity for comedy that he rarely got to use. All movie long, he takes every opportunity that arises to try to foist his apparently poisoned coffee on the rest of the cast, and each time he is rebuffed— Gelman doesn’t want to be kept awake; Henry and James get so distracted arguing that they set their cups down untouched; the coffee was percolated and Tuttle only drinks drip-brewed. The way Lugosi portrays the escalating frustration bubbling behind the façade of solicitous calm that one expects of a good butler is just about perfect. In its way, it makes One Body Too Many one of the minor highlights of Lugosi’s career.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact