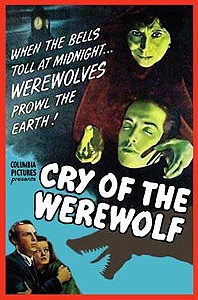

Cry of the Werewolf (1944) **

Cry of the Werewolf (1944) **

Columbia Pictures came late to the party. Having all but sat out the horror boom of the early 1930’s, they jumped in with both feet when interest in (and support for) the genre revived in 1939, cranking out a fairly respectable total of five scare films by 1942. Those early-40’s Columbia horror pictures were all just variations on the same premise, though. All starred Boris Karloff as a doctor or scientist of questionable ethics and/or sanity, using the fruits of his recent research to even the score with those who had meddled in or obstructed his work. The template was not original to Columbia (The Man Who Changed His Mind, a 1936 mad doctor movie from Gainsborough-Gaumont British, is an obvious precursor), but the studio certainly made it their own with The Man They Could Not Hang and its successors. Five such movies over the course of four years was rather a lot, however, and by 1943, it was plainly time to try something different. Sadly, that different something ended up being rip-offs of other studios’ hits. First came The Return of the Vampire, a remarkably shameless Universal pastiche. Then, in 1944, the folks at Columbia decided to try their hands at copying Val Lewton. As Cat People cash-ins go, Cry of the Werewolf is a halfway-credible effort, getting more right than most of the comparatively rare Lewton wannabes, but its very success in resembling the contemporary output of RKO’s B-unit serves to underscore its complete lack of the creativity that was the Lewton pictures’ real claim to distinction.

Somewhere in the vicinity of New Orleans, there’s a great, big house that used to belong to the LaTour family. Now it is both a rather tacky museum dedicated to the supernatural, and the base of operations for a researcher into paranormal phenomena by the name of Dr. Charles Morris (Fritz Leiber, from the 1943 version of The Phantom of the Opera, the namesake father of the well-known sci-fi author). The reason Morris has set up shop in the old LaTour mansion (and converted its first floor into a macabre tourist attraction in order to finance his investigations) is that Marie LaTour, the last member of the family to live there, is reputed to have been a werewolf. Years ago, she supposedly killed her husband after he discovered her secret, and then fled into the wilderness never to be seen again. Morris is very interested in the legend, and has spent years attempting to figure out what became of the LaTour woman. He thinks he’s getting close to completing the puzzle, too— so close, in fact, that he has summoned his son, Bob (Stephen Crane), home from Europe in order to share with him the discovery he feels himself on the verge of making. Unfortunately for Morris, he is not alone in his optimism. Jan Spavero (Ivan Triesault, of Journey to the Center of the Earth and The Amazing Transparent Man), the museum’s Gypsy janitor, believes that his boss has learned or soon will learn the location of Marie’s secret grave, and he clocks out early on the night of Bob’s return to pass the word along to the other members of his tribe. You see, their leader, Princess Celeste (Nina Foch, from The Return of the Vampire and 1001 Nights), is Marie LaTour’s daughter, and she wants to make sure that mom remains comfortably shrouded in legend. There are three reasons for this, or so it would seem: first, Marie really was a werewolf; second, Celeste is a werewolf, too; and third, this particular band of Gypsies is a secretive bunch, and just can’t bear the thought of the professor’s snooping. When Morris’s assistant, Ilsa Chauvet (Rocketship X-M’s Osa Massen), drives off to meet Bob’s plane, Celeste drops in on her ancestral home, butchers the old man, and conceals his body in a secret passage that none of the house’s current occupants seem to know about. There’s still one employee left in the museum, though, and Peter (John Abbott, from The Woman in White and The Vampire’s Ghost) comes rushing to help when he hears Morris screaming. But because he arrives just in time to witness the unnatural spectacle of the Gypsy girl’s transformation back into her human form, he’s going to be too busy drooling on himself and gibbering to be of any help once Bob and Ilsa arrive.

Bob Morris wastes no time in calling the police. Lady Luck kicks him in the balls, however, when she sends him Lieutenant Barry Lane (Barton MacLane, of Unknown Island and The Walking Dead) and a lower-ranking detective named Homer (Robert Williams, from This Island Earth and The Bat)— it isn’t quite as bad as getting stuck with Mulligan, Harrigan, and Garrity, but it’s pretty close. Lane concludes immediately and for no obvious reason that Ilsa killed Dr. Morris, and he is absolutely crestfallen when Pinkie (Fred Graff), the technician at the police evidence lab, informs him that the fingerprints found near the body don’t even faintly resemble Miss Chauvet’s. The bumbling cops come slightly closer to the truth with their second try, when they decide in an almost equally hasty and unsubstantiated manner that Spavero is the culprit. The one thing they absolutely will not countenance is the idea that Morris was slain by a werewolf— or an ordinary wolf, either, for that matter— despite the fact that their own medical examiner attributed the researcher’s death to an unknown animal or animals. Their resistance persists even after Spavero himself turns up dead and mutilated, Celeste having decided that the official scrutiny under which the janitor had come was turning into an unacceptable liability.

It thus falls to Bob and Ilsa to do most of their own detective work. Ilsa had noticed her employer’s research notes burning in the fireplace right around the time that she and her love-interest discovered the body, and she was able to rescue them from total destruction. Bob reasonably concludes that the burned notes must contain a clue to his father’s murder, and he begins using high-tech means to render them at least partly legible again. Doing so reveals the broad outlines of Dr. Morris’s findings regarding Marie LaTour, including the interesting tidbit that she eventually wound up in Transylvania— from which both Ilsa and Spavero originally hailed, by the way (which really makes you wonder about their French and Italian surnames, respectively)— among a tribe of Gypsies. Those very same Gypsies, as we know, are now based in the bayou not far away, and it doesn’t take Bob long to trace the connection between them and the recently deceased Jan. Bob arranges to ask Princess Celeste a few questions at the coroner’s inquest for Spavero, then drops in on Mr. Adamson (Milton Parsons, from Fingers at the Window and The Monster that Challenged the World), who owns the funeral parlor favored by Celeste’s tribe, in the hope of digging up some Gypsy burial records. Adamson’s professional ethics prevent him from assisting Bob, but an encounter with Celeste at the funeral parlor gives him what seems, at the time, like some useful information. What Bob doesn’t realize is that the princess has taken the opportunity presented by their meeting to place him under a love spell, neutralizing him, or so she hopes, as a potential threat. Of course, Celeste has failed to realize something herself— Bob might not recognize the significance of that doll she slipped him, but Ilsa sure does. Apparently, if you want to fight a Transylvanian Gypsy, you need a Transylvanian Gypsy of your own.

There are so many things for which I’d like to be able to give Cry of the Werewolf credit. For one thing, it’s got a female werewolf, and one whose lycanthropy is a power she consciously controls, rather than purely a curse with which she has been somehow saddled. Neither one of those notions would get much use in the werewolf (as opposed to were-cat or were-snake) subgenre until the 1980’s, so seeing them here ought to be a big deal. Celeste’s wolf form is portrayed by a live animal, rather than with a set of snaggly dentures and a bunch of glue-on yak hair, an approach that had been seen only once (and only briefly, at that) since 1913’s The Werewolf, and would not be seen again until possibly as late as The Company of Wolves in 1984. Cry of the Werewolf gets a lot of use out of artfully composed shadows and unconventional camera angles, and it makes an honest stab at working primarily by suggestion. I want to give the movie credit for those things, but in each case, there’s some caveat stopping me. It’s blatantly obvious that Cry of the Werewolf’s lycanthrope is a woman not because earlier cinematic werewolves weren’t, but because Irena Dubrova in Cat People was. What might have been an elegant means of sidestepping the pitfalls of crummy wolf-person makeup falls as flat as any but the worst examples of the standard procedure (The Mad Monster, for instance) because the dog standing in for Celeste’s four-footed guise suggests that the movie should perhaps have been called Cry of the Were-Mutt instead. The nifty lighting arrangements and camera setups are merely direct cribs from Jacques Tourneur, and what’s worse, it’s clear that first-time director Henry Levin has only the dimmest understanding of why those tricks worked when Tourneur used them. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Levin’s obsessive overuse of cropping that shows Celeste only from the knees down. It has the desired effect in the stalking scenes, which what Tourneur used it for in Cat People, and again in The Leopard Man. But when Celeste is just standing there in the room with her foes— and especially when she’s just standing there in wolf form— the result is absurd. We know perfectly well that it’s her, and there’s no point in trying to create suspense when a confrontation is already in progress.

So far, my complaints with Cry of the Werewolf have all been in the form of “This would be good, except…” Alas, there are other defects that don’t have any sort of upside to them. The biggest of those is the handling of the police. My God, but these cops are an irritating bunch of monkey-fuckers! And as with the knees-down business in the face-off scenes, their annoying ineptitude is totally pointless. If writers Griffin Jay and Charles O’Neal wanted to keep Lane far enough behind the curve to place the onus of fighting Celeste squarely on Bob and Ilsa, just having the lieutenant butt up against the impossibility of lycanthropy should have sufficed. Why make him also a gun-jumping incompetent with a complete idiot for a partner? Heaven knows none of Lane’s or Homer’s antics are at all funny, and lowbrow comic relief was something that the movies which inspired this one always scrupulously eschewed anyway. The only way to make sense of it is to observe that Jay was a recidivist in this department, having junked up his screenplay for The Mummy’s Hand in exactly the same fashion. Another big problem concerns Stephen Crane’s acting. The dialogue doesn’t do him any favors, to be sure, but Crane is frankly almost useless— especially in those scenes where he’s romancing Ilsa. The casting people would have done much better to have switched him with John Abbott, who’d have been no stranger a choice for a romantic lead, and who succeeds in making Peter a memorable character despite having only a small handful of scenes early in the film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact