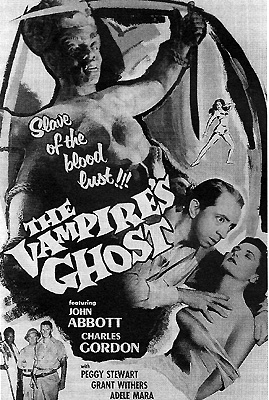

The Vampire’s Ghost (1945) **½

The Vampire’s Ghost (1945) **½

The really incredible thing about The Vampire’s Ghost is that it sort of almost justifies calling itself that. Obviously there isn’t a vampire’s ghost in the strict sense— for one thing, one has to ask what that would even mean, and for another, we all know by now that a genuine ghost is the very last thing one should ever expect to see in a wartime second feature with the word “ghost” in the title. But the vampire in this film is killed off and then resurrected about halfway through, so in a very oblique manner of speaking, he could be spun as his own ghost for the last twenty-odd minutes. That mid-course turn of events also hints at why I consider The Vampire’s Ghost to be an unjustly overlooked movie. No, it isn’t especially good on any absolute scale, but it represents an almost unparalleled effort to do something truly unique with a monster that most filmmakers both before and since have been incapable of conceptualizing except through the prism of Tod Browning and Bela Lugosi. Say what you want about The Vampire’s Ghost, but the one thing you can’t accuse it of being is another tired riff on Dracula.

There’s the setting, to begin with. I mean, really— when was the last time you saw a vampire flick set in colonial Africa? It was about the second Wednesday before never, I’m guessing. But Africa is indeed where Webb Fallon (John Abbott, from Cry of the Werewolf and A Thousand and One Nights) has wound up after 400 years of roaming the Earth in bloodthirsty melancholy. Fallon had been a captain in the fleet that fought off the Spanish Armada, recognized for special commendation by Queen Elizabeth I herself. Later on, however, he caused the death of a young woman (one assumes either that the method of her demise was extraordinarily foul, or that the victim was especially favored by the Almighty), and he has borne ever since the curse of undeath. Fallon now lives as an innkeeper in the Congolese rubber-planting settlement of Bakunda— which is perhaps a poor choice, as it seems to be the only place on the continent where the natives are hip to European-style vampirism. His activities have the field hands and their families thoroughly freaked out, so much so that they’re beginning to abandon the plantations in favor of the surrounding jungle. That’s about to become a real problem for Fallon, because if there’s one unbreakable rule in colonial Africa, its that you never come between a rich white guy and his extraction industry.

The rich white guy with whom we’ll mainly concern ourselves is Thomas Vance (Emmett Vogan, from Black Friday and Horror Island). He’s maybe the biggest planter in Bakunda, so he has more to lose than anybody from the spreading vampire panic. Mind you, Vance doesn’t understand that spreading vampire panic is behind the desertion of his workers— that would require listening to the Negroes, after all, and far be it from a man of his station to do that! Vance’s daughter, Julie (Peggy Stewart, of Terror in the Wax Museum and a largely forgotten late-70’s version of The Fall of the House of Usher), knows no more than her old man, and neither does her boyfriend and the planter’s right-hand man, Roy Hendrick (Charles Gordon). Even the local missionary, Father Gilchrist (Gran Withers), who at least understands the natives’ signal-drum code well enough to discern what everyone is so afraid of, is at a loss for ideas on how to deal with the situation. I suppose Gilchrist could gain some insight from his native sidekick, Simon Peter (Martin Wilkins, of Voodoo Woman and I Walked with a Zombie), but again there’s that “listening to the Negroes” thing. Ironically, Vance and his confidants are unanimous in believing that the one person with the experience they need in interacting with the locals from usefully non-condescending heights is Webb Fallon.

Naturally, Fallon doesn’t really want to get to the bottom of the vampire rumors, or put a stop to the killings that gave rise to them, but he does have appearances to keep up. Consequently, he agrees to accompany Hendrick on an investigatory safari into the depths of the jungle. Simon Peter gets tasked with recruiting and overseeing the guides and bearers, which is right inconvenient for Fallon. Father Gilchrist’s star convert is as sharp as any 1940’s jungle movie would allow a black guy to be, and while he understandably sees no point in mentioning any of this to Roy, Simon Peter knows what it means when Fallon casts no reflection in a mirror and emerges unscathed from a booby trap that should certainly have killed him. He also knows that vampires are vulnerable to silver weaponry, and as soon as the opportunity presents itself, he and one of the guides improvise a sliver-headed spear for use against the undead barkeep. It’s lucky for the conspirators in a sense that the safari comes under attack from a hostile tribe as soon as they’re well away from the town, because the attendant confusion makes it possible for Simon Peter to stab the vampire and pin it on the raiders. Unfortunately, though, the wound is not immediately lethal. In fact, Fallon retains the strength to hypnotize Roy, and to make him carry out the preparations that will ensure the vampire’s restoration at the next moonrise.

What follows is the only real nod to Dracula that The Vampire’s Ghost ever makes, as the conflict between Roy’s horror at what he as learned and the vampire’s post-hypnotic commands to reveal nothing of the incident to anyone brings on a mental collapse that turns Hendrick into the next best thing to Renfield. Africa being Africa, it’s easy enough for Fallon to pass Roy’s sudden madness off as a fever-induced delirium upon their return to Bakunda, so nobody suspects anything too untoward for quite some time. The need to keep a sharp eye on Roy coincidentally brings Fallon into prolonged contact with Julie, which eventually gets him thinking that maybe the next four centuries don’t have to be quite as lonely for him as the last four were. Hendrick is just thrilled about that, of course, but there’s nothing he can really do to oppose the fiend’s designs so long as he can count on lapsing into raving semi-consciousness every time he so much as thinks of mentioning Fallon and vampires in the same breath.

There are, however, a few others who might unwittingly do the dirty work for Roy. Fallon employs a dancer by the name of Lisa (Adele Mara, from The Catman of Paris and The Curse of the Faceless Man), and she’s been in the habit of keeping the vampire’s bed warm. (Webb doesn’t bother lugging any caskets around with him; the engraved wooden coffer he got as a thank-you gift from Queen Bess back in 1588 holds all the grave-earth he needs at any one time.) When Lisa finds out that Fallon has his eye on the Vance girl, she gets Hell-hath-no-fury pissed off about it. Nor is she the only enemy that Fallon has acquired for reasons other than drinking people’s blood. One of the regulars at the pub, a seaman called Barrett (Roy Barcroft, of Destination Inner Space and Billy the Kid vs. Dracula), just lost a fortune gambling with innkeeper, including even the title to his boat. If Lisa and Barrett put their heads together, they could be a real pain in Fallon’s ass. Meanwhile, let’s not forget about Simon Peter. That trick with the spear would have worked without Royfield to fuck it up, and a silver-pointed weapon isn’t the kind of thing you just leave behind in the jungle after you use it. Let’s not forget, either, that Simon Peter works for a man of the cloth. That’s a second source of supernatural power that he could potentially bring to bear if Gilchrist would drop the “Holy Father knows best” bullshit for fifteen minutes, and hear his valet out about what really happened on that safari.

I’m not going to defend The Vampire’s Ghost too strenuously, but I am going to defend it. There are just too many things that it gets right mixed in amid the dire dialogue (“Oh, a vampire! A dead man denied Heaven because of his crimes, doomed to remain on Earth in hideous semblance of life, sustaining his body on the blood of the living… Old medieval tommyrot!”), the cringe-inducing characterization of the natives, and the B-Western backlot sets feebly masquerading as a Congolese plantation town. Its vampire lore is commendably individualistic without straying so far from the standard interpretation as to provoke a Twilight-style hate-gasm from the serious fan of the subgenre. John Abbott is a weird casting choice, to be sure, but in an enjoyable way. After fifteen years of decadent aristocrats in opera capes, it’s fun to see a vampire who is instead a world-weary, low-born scoundrel. Furthermore, I got a huge kick out of Abbott’s portrayal of the character’s attitude toward his own immortality. In some scenes, Fallon is presented as being thoroughly sick of living, but he goes to great lengths to outmaneuver the various factions conspiring to destroy him anyway. That could easily have come across as incoherent characterization, but it makes perfect sense the way Abbott plays it. Fallon wants to die, sure— but not just yet, and certainly not from the machinations of these schmucks! Abbott also has great sarcastic fun with Fallon’s tendency to taunt Roy by actively helping him to learn everything he would need to go into the Fearless Vampire Killer business, if only that damned post-hypnotic suggestion weren’t in the way. Some of those exchanges are almost as brilliant as the bit in Count Yorga, Vampire where Yorga relieves one of the Van Helsing wannabes arrayed against him of his stake, looks it over briefly, and then hands the weapon back with a politeness far more contemptuous than any overt show of disdain. I found the unorthodox setting to be a point in the movie’s favor, too. Most reviewers who take notice of The Vampire’s Ghost at all seem to kvetch about seeing a traditional figure of gothic horror mucking about in the jungle like Trader Horn, but the Congo of the 1940’s seems to me like a pretty great place to be an undead bloodsucker. What with the porous frontiers, the reflexively corrupt administrations, the ineffectual policing, and the utter disregard of the colonial authorities for the well-being, safety, and human rights of the natives, it’s hard to imagine a much better base of operations for such a predatory being. Besides, in a mythos that explicitly grants Christianity a monopoly on holiness, a land of benighted pagans has to be awfully attractive to a creature whose most serious weaknesses concern the trappings of the divine. The Vampire’s Ghost never rises too far above its origins as a disposable freebie rounding out a theater bill, but rise above them it does.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact