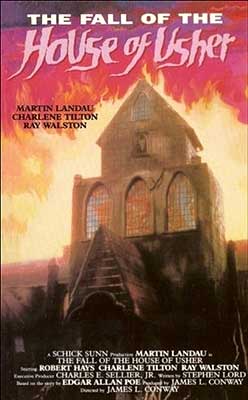

The Fall of the House of Usher (1979) ***

The Fall of the House of Usher (1979) ***

Those of us old enough to remember the 1970’s (or at least that part of the 80’s that didn’t yet realize the 70’s were over) might not consciously recall the name, Sunn Classic Pictures, but it was hard to make it through those years without becoming well acquainted with their flagship product line. Although Utah, where the company was based, didn’t have much in the way of film-production infrastructure, you didn’t need much to crank out bullshit “documentaries” about UFOs, near-death experiences, psychic phenomena, or the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Films like Beyond and Back and The Mysterious Monsters were only part of the Sunn Classic story, though. In 1977, comparatively flush with cash after six years of convincing the credulous that aliens hired Bigfoot to shoot JFK, the company took its game up a notch, and began making narrative movies primarily for sale to television. And in an especially strange twist, at least eight of these new telefilms were cross-branded with the venerable Classics Illustrated comic book series, which Sunn Classic’s new parent company, Schick (the same outfit that made the disposable razors), had also acquired a few years earlier. The Classics Illustrated pictures seem mostly to have been broadcast on NBC as a sort of sub-series within that network’s “The Big Event” TV movie program— which somewhat confuses the issue of which and how many of the things Sunn Classic actually produced, because NBC developed a habit of repackaging telefilms from other sources (the 20th Century Fox Television The Red Badge of Courage, for example) as Classics Illustrated entries in reruns. But so far as I can determine, The Fall of the House of Usher was the last Classics Illustrated film made before Sunn Classic was sold off again to the Cincinnati-based Taft Broadcasting Company, and reorganized into Taft International Pictures (which we’ve encountered before as producers of The Boogens). I’m not entirely sold on some of the more drastic changes that writer Stephen Lord made in order to stretch the slender source material out to feature length, but this Fall of the House of Usher offers an interpretation of Edgar Allan Poe’s story that I can just about promise you’ve never seen anywhere else.

In the autumn of 1839, construction engineer Jonathan Cresswell (Robert Hays, from The Initiation of Sarah and Cat’s Eye) receives an unexpected letter from his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher (Martin Landau, of Without Warning and The Being), whom he has not seen in over 20 years. The Usher family, as Cresswell remembers it, was both immensely wealthy and immensely strange, living as recluses in a forbidding mansion that grew like a cancer out of a Medieval keep over a period of 800 years; although the building was originally erected outside of Marseilles, it had been dismantled, shipped across the Atlantic in who knows how many cargo holds, and reassembled on American soil sometime in the 1600’s. Indeed, that long-ago uprooting may lie at the bottom of the trouble that provokes Roderick to call upon Jonathan now, for it seems that the building is in danger of falling in. Usher is hoping that his old friend can apply his professional skills to save the house, but there’s something else, too— something that Cresswell can’t quite work out from the letter alone. As Jonathan explains to his new bride, Jennifer (Charlene Tilton), Roderick also rambles on at length about a hereditary affliction of his family that has manifested itself at last in both him and his younger sister, Madeline (Bless the Child’s Dimitra Arliss). What Jonathan finds disquieting is that Roderick seems incoherently to imply a connection between the threatened collapse of the house and the illness of the Ushers themselves, so that by preventing the former, Cresswell might somehow bring the latter into remission as well. Quite frankly, the letter doesn’t sound like the work of someone entirely sane, although Jonathan himself would hardly say such a thing about a dear old friend like Roderick Usher. Or at any rate, he’d hardly say it yet.

En route to Raven’s Head Lake, where the Usher place stands, the Cresswells’ carriage throws a wheel, forcing the couple to backtrack on foot to the nearest village in the hope of hiring both a mechanic and a ride the rest of the way to their destination. That proves more difficult than they expected, for the House of Usher has roughly the same reputation in these parts as Castle Dracula has in Transylvania. In the end, Jonathan and Jennifer are just lucky that one of the regulars at the tavern where they stop to inquire has racked up a five-dollar bar tab (cognac ran about 40 cents per quart in the 1830’s, so that’s a hell of a lot to spend on beer and whiskey!), and has been cut off until he squares up. Mr. Finney (Michael Ruud, from Hangar 18 and Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers) agrees to take the Cresswells to Raven’s Head Lake, and to fix their carriage for them in the morning, but it’s going to cost them the full five bucks that he owes the barmaid (Peggy Stewart, of Something Weird and Terror in the Wax Museum). Even then the couple’s unexpected adventure isn’t over, for Finney drops them off fully a quarter of a mile from the mansion itself, and the Cresswells are attacked by a vicious dog before they reach the safety of Roderick’s front door. Again, though, luck is at least begrudgingly on their side. The animal turns out to be as weak and sickly as the trees and underbrush along the shores of Raven’s Head Lake, all of which look to be rotting to punk where they stand. One good wrench from Jonathan breaks the dog’s neck, after which he can at last turn his attention to the disturbing fact that it looks exactly like a pet that he remembers the Ushers having more than two decades ago.

Jonathan and Jennifer are greeted at the door by Thaddeus (Ray Walston, from Galaxy of Terror and Saturday the 14th Strikes Back), the Ushers’ aged butler. Sharply admonishing the guests to keep their voices down and to walk only on the thick runners of carpet that crisscross all of the manor’s floors, the old man shows them to their rooms— their separate rooms— and assures Jonathan that the master of the house will see him presently. When the Cresswells protest the sleeping arrangements, Thaddeus manages to sound almost apologetic while explaining that nothing can be done. None of the rooms in the house are configured for more than one sleeper, and all the furniture is bolted permanently to the floor. The rationale behind all this rigmarole remains hidden, however, until the promised reunion between Jonathan and Roderick. It seems that the entire Usher lineage since time immemorial has suffered from a degenerative nervous condition, which begins with a preternatural sharpening of the senses, progresses through incurable insanity as the patient’s mind snaps under the burden of constant overstimulation, and ends in a mercifully premature death. Not one of Roderick’s ancestors, to the best of his knowledge, ever made it past the age of 37. Roderick himself is just two weeks shy of matching that record— although to look at him, you’d swear he was pushing 60 instead. Usher attributes his relative longevity and health in the face of the family affliction to the drastic measures he has adopted to coddle his and his sister’s fragile nerves. Neither Roderick nor Madeline ever leave the confines of their house, nor have they ever entertained guests until now. They eat only flavorless grain mush, speak only at a whisper when it is necessary to speak at all, and keep the whole house as close to lightless as possible, even at high noon. Even so, Madeline is noticeably cracking up— so much so that Roderick intends to keep her sequestered throughout the duration of the Cresswells’ visit. And to judge from malevolence in Madeline’s eyes when Jennifer encounters her in the library despite Roderick’s best efforts, the elder Usher is indeed wise to restrain his sister’s movements while outsiders are about. For that matter, nailing down everything in the house that’s heavy enough to be used as an improvised bludgeon starts looking like a really sound policy, too.

Jonathan’s inspection of the house the following morning reveals a spreading crack in one of the load-bearing walls, beginning at the very foundation and reaching all the way to the eaves. Cresswell figures he might slow down the mansion’s self-destruction by filling the gap with mortar and erecting a truss of timbers around the crack, but in the long run, the only solution he can see is for the Ushers to move out, sell their land, and find a new place to settle. Roderick won’t hear of that, of course, so Jonathan gets to work on his stopgap repairs. A funny thing happens as the work progresses, though. The more securely Jonathan shores up the crack, the more vigorous his host seems to become. But at the same time, Jennifer awakens one morning inexplicably enfeebled, as if something in the house were making her ill to compensate for Roderick’s recovery. Usher has an explanation for that, too, although his guests won’t want to hear it. Hidden in the cellar, at the center of the family crypt, is the secret chapel of evil where the founder of the House of Usher presided over a devil-worshipping cult. Subsequent generations broke with the traditions of diabolism and human sacrifice, but they did so too late. The house itself is now demonically possessed, and the evil spirit within it will not be satisfied until it has punished the Ushers for their infidelity by extinguishing the entire lineage. That yarn is enough to convince Jonathan at last that his old friend really has gone insane, but events following the sudden, accidental death of Madeline will change his mind about that right quick. After all, corpses entombed beneath non-demonically possessed houses don’t typically rise again as murderous zombies…

That final intrusion of the overtly supernatural is why I’m somewhat conflicted about The Fall of the House of Usher. Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” was a symbolic musing upon morbid psychological states, the crushing weight of the past, and the degenerate decadence of aristocracy. To turn it into a strictly literal story about Satanism, demonic possession, and hellfire-fueled zombies is, at a minimum, in the gray zone where legitimate reinterpretation starts fading into missing the point. It also relocates the horror of the climax to a much cruder and simpler place if Madeline truly is dead when Roderick shuts her up in that coffin, while simultaneously negating the narrative purpose behind the Usher Syndrome’s most distinctive symptom. All that said, though, I can’t deny the impact that Dimitra Arliss’s Madeline makes as a forerunner to the supernatural slashers of the late 1980’s. She’s an impressively menacing presence, and taken on its own, without reference to either the source material or any previous adaptation, the running battle against her as the house finally disintegrates under a barrage of lightning brings this movie to a strong and memorable conclusion.

Also strong and memorable is Martin Landau’s performance as Roderick Usher. At first I thought he was an odd choice for the role. Most cinematic interpretations of the character go in a Byronic sort of direction, and that is not an adjective that I would ever use to describe Martin Landau. Also, Landau was one of those guys who spend most of their lives looking markedly older than they actually are, which tends to go against my default mental image of languid aristocrats looking unnaturally preserved by their own idleness. It works, though, because this version of the story implicitly identifies premature decrepitude as the proximate cause of death from the Usher Syndrome. Indeed, Landau enters the picture wearing old-age makeup to intensify the sense that there’s no way this guy is only 37 years old— makeup which then comes off as Jonathan makes what repairs he can to the fissure endangering the house. Meanwhile, seeming to realize that there’s no point in shooting for a Byron type, Landau plays Usher more like one of H.P. Lovecraft’s tortured, maddened survivors of a brush with the otherworldly. This is by no means my favorite portrayal of Roderick (which, for the record, is Tom Tryon’s, in a 1956 episode of “Matinee Theater”), but it might be the most distinctive version I’ve seen so far.

If you’ve watched more than a couple adaptations of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” you’ll surely have noticed that there tends to be something of an inverse relationship between the effectiveness of the actor playing Roderick and that of the one playing the part that this version calls “Jonathan Cresswell.” (I refer you once again to that “Matinee Theater” episode, in which the visiting friend was played by D-list mid-century lump-man Marshall Thompson.) That holds true here as well, for although Robert Hays isn’t notably bad as Cresswell, he’s still forgettable enough to constitute the weak link in the cast. Also, while this is scarcely Hays’s fault (especially in a movie from 1979!), I find it distractingly difficult to watch him in anything without imagining him as Airplane’s Ted Striker. Lots of intrusive thoughts about how Jonathan and Roderick know each other from flying together over Macho Grande, you know? Fortunately, Poe himself made the narrator of the tale more of an onlooker than a protagonist, and this Fall of the House of Usher follows his example faithfully enough on that score (if perhaps on no other) to limit the damage that even a much worse actor than Hays could have caused.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact