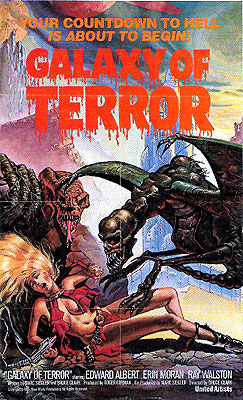

Galaxy of Terror/Mind Warp (1981) **½

Galaxy of Terror/Mind Warp (1981) **½

New World Pictures produced two blatant rip-offs of Alien in the early 1980’s. The second one, Forbidden World, is very much what you’d imagine from reading that sentence: unabashedly crass, conspicuously cheap, vibrantly sleazy, and well seasoned with special effects footage recycled from Battle Beyond the Stars. Galaxy of Terror, however, is a tad more ambitious. Although it can hardly be accused of failing to steal from Alien every chance it gets, it isn’t just another monster movie set in outer space amid a high-tech warren of under-lit tunnels and hallways. Instead, Galaxy of Terror impresses that newly popular template upon a somewhat older and significantly more eccentric tradition of mystical, acid-headed sci-fi influenced by European comics. It’s the Alien rip-off you’d expect from René Laloux, not some bunch of louts working for Roger Corman.

Things are going very badly on the unexplored planet Organthus. The Remus, a Class III mission ship, has landed there to reconnoiter, and something is killing the crew with great alacrity. We join the action just as the last of the Remus astronauts seals himself into one of the ship’s compartments, which ought to be enough to protect him from anything stalking the rest of the vessel. Somehow, though, whatever it is (we don’t get to see) reaches him anyway— without apparently forcing its way through the laser-welded door or scuttling in through one of the ever-popular ventilation shafts.

Meanwhile, on Xerxes, apparently the Remus’s homeworld, the godlike Planet Master (whose identity, obscured by a swirling halo of orange-red light, will be a major third-act plot point) is playing some manner of oracular video game with a space witch called Mitri (Mary Ellen O’Neill, from Beyond the Universe and The Big Brawl). When word reaches them that one of the Planet Master’s ships has disappeared on Organthus, he makes what is apparently an extremely bold move in the game, one which he seems to have wanted to carry out for a very long time. After convincing Mitri that he really means to do whatever he just did, the Planet Master dismisses her, and orders Commander Ilvar (Bernard Behrens, of The Changeling and The Man with Two Brains) to ready a second Class III mission ship to mount a voyage of rescue to Organthus. Ilvar will lead the undertaking personally (evidently not something that men of his age and rank normally do), and the Planet Master, even more extraordinarily, will select the rest of the crew himself.

Ilvar’s ship is to be the Quest, piloted by Captain Trantor (Grace Zabriskie, from Servants of Twilight and Child’s Play 2). Trantor, not to put too fine a point on it, is crazier than a shithouse rat, although she comes by it honestly. 25 years ago, she was the sole survivor of the mission ship Hesperus, the crew of which was massacred by aliens. Trantor doesn’t like to talk about it, so don’t expect more than the most tantalizing hints. Also aboard the Quest are Tech Chief Dameia (Taaffe O’Connell, of New Year’s Evil and The Stoneman) and Tech Second Ranger (Robert Englund, from Dead & Buried and Night Terrors), who I gather are something like engineers. The main crew consists of Baelon (Zalman King, of Blue Sunshine and Trip with the Teacher), Cabren (Edward Albert, from Killer Bees and The House Where Evil Dwells), Alluma (Watermelon Man’s Erin Moran), Quuhod (Sid Haig, from Lords of Salem and Spider Baby, or The Maddest Story Ever Told), and Cos (Jack Blessing). Baelon and Cabren have a past together, and don’t like each other very much. Alluma is psychic, which appears actually to be her main function on the team. Quuhod is some manner of martial arts weirdo trained in the use of two triple-bladed, crystalline throwing knives. And Cos is a green recruit who’s never been out in space before. Finally, there’s Kore (Ray Walston, of Popcorn and Blood Relations), the cook. It’s odd that he’s even on this mission, since most spacecraft have machines to keep the crew fed.

No sooner does the Quest arrive at Organthus than some mysterious force reaches out from the surface and drags the ship into the atmosphere. Trantor manages to get enough control over the descent to effect a relatively smooth landing, but the Quest still takes sufficient damage that it won’t be lifting off again without some minor repairs. The ship doesn’t need to move for the crew to do their main job, however, so Ilvar sends Baelon, Cabren, Alluma, Quuhod, and Cos over to the Remus to see what they can find while the tech staff get to work. What the rescue team discovers is a ship full of corpses— but not enough of them to account for everyone they’re supposed to save. Since Organthus is marginally capable of supporting human life, it’s possible the remaining four astronauts are still out there somewhere. Two members of the party, however, notice something their fellows do not. Alluma keeps sensing life signs on the ghost ship, but they fade in and out in a way that she’s never encountered before. And Cos keeps seeing movement in his peripheral vision, as if something were hunting him through the Remus’s corridors. Shortly before they all pack up for the march back to the Quest, Alluma gets the weirdest feeling, almost as if those inexplicable life signs were coming from Cos. A moment later, the instant all of his fellows have turned their backs to him, Cos is killed by an invertebrate monster that appears literally out of nowhere behind him. It’s gone again by the time the others realize that he’s in trouble.

Cos’s fate leaves his shipmates understandably flummoxed. Almost as puzzling is a discovery that Ilvar makes on the bridge of the Quest— there’s something out there that scrambles the ship’s scanners whenever they sweep over it. Figuring that the source of the disruption might also account for the force that pulled the Quest out of orbit, Ilvar leads Dameia and the survivors of the first away team on a second exploratory trek. Their goal turns out to be an ancient pyramid more utterly lifeless than anything Alluma has ever sensed before. And yet something is in there, manifesting itself in ways keyed to the astronauts’ greatest fears: Ilvar’s worry that his age has rendered him no longer fit to lead; Trantor’s post-traumatic stress disorder; Alluma’s claustrophobia; Dameia’s horror of vermin; Baelon’s macho insecurity; Ranger’s nagging sense of his own incompetence; Quuhod’s total dependency upon his martial arts skills. The only members of the crew who seem to lack such a psychological Achilles heel are Cabren and, curiously, Kore. It’s about here that you should start thinking back to that bit with Mitri and the Planet Master playing Prophecy Qix together, and pondering what Lord Glowyhead might really have been up to.

To the extent that anybody remembers Galaxy of Terror today, they remember it as that movie where a woman gets raped to death by a worm. It was probably inevitable that that would become this film’s legacy, because once you see it, you’re never going to forget. But to recall Galaxy of Terror solely as Rapeworm: The Motion Picture doesn’t do it justice. In fact, part of why that scene stands out so much is that it’s such a bizarre non-sequitur, far skuzzier and more mean-spirited than the rest of the film. The only respect in which the Rapeworm incident is indicative of Galaxy of Terror as a whole is that this movie is consistently willing to do things as arrestingly weird as that, with just as little warning or explanation.

That scatterbrained screwiness is both Galaxy of Terror’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. On the upside, it means there’s no other Alien rip-off quite like this one. Seriously, find me another that has a psychic, a space ninja, a Bruno Mattei Action Movie Asshole, a Sinister Cook straight out of a 1940’s jungle adventure flick, and the sci-fi equivalent of a deranged ‘Nam vet among the astronauts. Find me another where the monster is the externalization of the protagonists’ fears and anxieties. Find me another where the Weyland-Yutani stand-in [spoiler ahoy!] is a guy who wants to get out of the god business, but can’t unless he arranges for some other schmuck to accept apotheosis in his place. Hell, just show me another that has a space witch for no fucking reason. This kind of wide-ranging eccentricity is the best thing a rip-off can bring to the table, especially if it’s going to resort to such open thievery as, for example, Commander Ilvar’s solo rappel into the bowels of the pyramid. At the same time, though, writer/director Bruce D. Clark isn’t very interested in whether all those disparate pieces fit together neatly, and he treats it as our problem if we can’t make them fit. It takes a much better filmmaker than he is to get away with that.

The other big “good news/bad news” situation in Galaxy of Terror concerns the look of the film. The production design is superior to that of any contemporary futuristic horror movie save the real Alien, and the standard of construction for the sets, props, and miniatures is astoundingly high. It’s a little thing, but notice that all the myriad switches, lights, and knobs at the Quest’s control stations have their functions clearly labeled, just like their counterparts in a real-world aircraft cockpit. Nobody has to guess which way is on and which way is off, and there’s no mistaking the atmosphere recirculator fan for the reactor core ejector. You don’t see that kind of attention to detail nearly often enough. The mission ship models are simple yet imaginative, practical yet distinctive, in a way that underscores how the late 60’s through the mid-80’s were something of a golden age of movie and television spaceship design. I mean, if something like Galaxy of Terror could do this well… Then again, maybe we shouldn’t be too surprised at this movie’s success on the design and construction front, because one of the effects people here was a kid by the name of James Cameron, who as you might have heard went on to quite a career in effects-heavy sci-fi and action movies. Galaxy of Terror also sports some really good monsters, with about an even mix of stop motion and puppetry used to bring them to life. My favorites are the barely glimpsed things pursuing Cos through the Remus, but Rapeworm is pretty magnificent, too. (Mind you, I’m sure much of my affection for the latter creature in particular stems from the wicked thrill of seeing a dead ringer for Eiji Tsuburaya’s Mothra larvae behaving so abominably.) I said this was another case of “good news/bad news,” though, so here’s the bad news: All those gorgeous sets and models and monster puppets? You can barely see them because cinematographer Jacques Haitkin shot the whole damn movie under about 40 lumens of light. Galaxy of Terror is almost as muddy as Humongous, without the excuse of a serious effort to make footage shot in the woods at high noon look like it’s taking place in the middle of the night. It’s as if Haitkin or Clark heard somebody snarking that all it took to make an Alien clone was a rubber suit and a lightless corridor, and said, “Lightless, eh? I’ll show you lightless!”

Finally, Galaxy of Terror has one weakness that does not come packaged with a countervailing strength. In its great hurry to get the Quest crew onto Organthus so that they and their fears can get down to business, this film forfeits any chance to work as well as its model. That’s because the whole story hinges on the characters’ psychological makeup, but unlike in Alien, we barely get to know any of them before they start dying. In fact, in a few cases— Ranger especially— we have to deduce what foibles the pyramid force is exploiting by reasoning backward from the manifestations it adopts to attack them. It’s possible that these are Corman’s fingerprints we’re seeing rather than Clark’s, as he was notorious for having his directors at New World pick up the pace and keep down the running time, based on his (probably accurate) estimate of the drive-in crowd’s average attention span. If so, then this is one time when Corman’s instincts worked against the film. Especially given the nature of the threat the Quest crew faces on Organthus, it was vital that we should spend some time with these people, like we do with their counterparts aboard the Nostromo before they pick up their monstrous hitchhiker. With the first act as stunted as it is, Galaxy of Terror comes perilously close to reducing itself to a Friday the 13th-like parade of arbitrarily contrived killings.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact