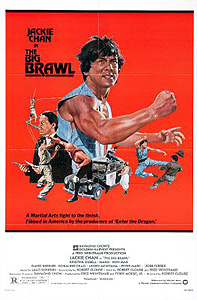

The Big Brawl / Battle Creek Brawl / Battle Creek / Sha Shou Hao (1980) ***½

The Big Brawl / Battle Creek Brawl / Battle Creek / Sha Shou Hao (1980) ***½

These days, practically everybody has some idea who Jackie Chan is. Even audiences that would never bother with any of his Hong Kong martial arts films from the 70’s and 80’s will have seen at least a commercial or two for Rush Hour or Shanghai Noon. Even some of his more recent foreign-made films, like Rumble in the Bronx and Legend of the Drunken Master, have seen relatively wide release and a modicum of box office success in the United States. What is less well known is that Chan had tried once before to break into the US market, and met with a much colder reception than he enjoyed in the 1990’s.

Cast your mind back about three decades. By that point, Chan had spent several years laboring futilely to live up to the hopes of Hong Kong producer Lo Wei that he would become the much sought-after “next Bruce Lee,” appearing in one relatively dismal flop after another. Then, in 1978, he took on a string of projects that turned his career around. The first was Half a Loaf of Kung Fu, which marked Chan’s earliest attempt to fuse kung fu with slapstick comedy. Lo Wei considered it unreleaseable (it sat on the shelf for two years before the producer changed his mind), but that didn’t stop Yuen Woo-Ping from casting Chan in Yuen’s directorial debut, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow, which also handled the martial arts with a lighter touch than was standard at the time. It made a great deal of money, but it was really only the warm-up for the film that made Chan one of the biggest stars in Hong Kong: Drunken Master. Drunken Master also attracted notice on this side of the Pacific, where it cleaned up at the drive-ins, grindhouses, and Chinatown theaters of the US, and with that in mind, the folks in charge at Golden Harvest (then Hong Kong’s biggest film distribution company) signed the newly risen star for a movie they were developing as a Hollywood co-production. It must have seemed like a can’t-miss proposition: Hong Kong’s new screen hero teams up with its top cinematic moneymen, drawing upon the resources of the movie capital of the universe, while Enter the Dragon director Robert Clouse runs the show. The trouble with sure things, though, is that they frequently aren’t, and The Big Brawl/Battle Creek Brawl/Sha Shou Hao could scarcely have disappointed its backers more. In retrospect, the reasons why are obvious. Chan had made himself a star precisely by rejecting the mantle of Bruce Lee, so pairing him with the director of Lee’s breakout hit probably wasn’t such a brilliant idea. Meanwhile, one result of the collaboration between US and Hong Kong filmmakers was a compromise in the feel of the film, which ended up being too Western for the core kung fu audience, but too foreign for most fans of traditional Hollywood action movies. Finally, its American distributors made the terrible mistake of marketing it as if it were a conventional kung fu revenge melodrama, which is the farthest thing in the world from what The Big Brawl really is. But if you accept The Big Brawl for the compromise that it represents, it is a much more rewarding movie than its reputation and initial box office performance would suggest.

We begin with a scene that could not possibly seem any more out of place in a kung fu movie. In the muddy main thoroughfare of some rural town in 1930’s America, a bare-knuckle street fighting match is going on. It’s an entirely one-sided affair, with the gargantuan Billy Kiss (H. B. Haggerty, from Deathsport and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century) pounding the living shit of a much smaller cartoon Irishman. From what we can gather by listening to the announcers, this guy Kiss (so called because of his gimmick of giving his opponents the Kiss of Death before finishing them off) is pretty much the biggest name on the rural American bare-knuckle street fighting scene, and is the odds-on favorite to take the world championship title at Battle Creek, Michigan, in a few months.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, a Chinese restaurateur named Kwan (Chao Li Chi, from Big Trouble in Little China and Warriors of Virtue) is having some difficulties with the mafia. Goons working for a mobster named Domenici (Jose Ferrer, of The Swarm and Dracula’s Dog) keep demanding protection money from him, and while he has so far managed to refuse without getting any of his limbs broken, it hardly seems as though that state of affairs can continue much longer. So it’s a good thing for Kwan that his younger son, Jerry, is played by Jackie Chan. Dad disapproves of the whole business, but Jerry has been studying kung fu under his uncle Herbert (Mako, from Conan the Barbarian and Robocop 3, playing essentially the same character he always does), and he’s become quite good. The next time Domenici’s men show up with trouble on their minds, Jerry gives them all they can handle, beating the lot of them senseless and making it look like a series of clumsy accidents while he’s at it. He repeats the performance when a bunch of gangsters put in an appearance at the side-street roller derby Jerry and his Anglo girlfriend, Nancy (Kristine DeBell, from Lifepod and the X-rated version of Alice in Wonderland), had entered. In fact, Jerry makes himself such a pain in Domenici’s ass that the mafioso eventually decides to import some Chinese muscle to deal with him specifically. Not that it gets him anywhere, mind you.

It’s while Domenici is watching Jerry flatten his two kung fu hit men that a brilliant idea occurs to him. You see, a rival of Domenici’s by the name of Leggetti (Ron Max) happens to manage Billy Kiss. Domenici knows there’s a fortune to be made on the betting that will surround the Battle Creek championship bout, provided he can find a way to rig it so that Kiss loses. Now most gangsters would just pay the man to take a fall, but Domenici thinks he can do even better than that. All he needs to do is figure out a way to force Jerry Kwan to fight for him in Battle Creek. Opportunity knocks in the form of Mae (Rosalind Chao, of Slamdance and An Eye for an Eye), the fiancee of Jerry’s older brother. It’s an arranged marriage, neither participant having ever laid eyes on the other, and Jerry is supposed to go out to San Francisco to collect the girl when her ship comes in from China. When he does, Domenici’s men swoop down and abduct her, and then let Jerry know just what they want from him. They’ll hold onto Mae until after Jerry wins the Battle Creek brawl for them; at that point, they’ll let the girl go and consider their business with Jerry concluded. And just to show that they understand the delicacy of Jerry’s situation, the mobsters even supply him with a replacement girl to bring home to his brother— since he’s never met Mae before, he’ll never know the difference, right?

Naturally, Jerry goes to Uncle Herbert for assistance and advice as soon as he’s back in Chicago. But despite their best efforts, the two men just aren’t able to get Mae away from the gangsters, and Jerry eventually resigns himself to doing things Domenici’s way. Even that may not get Jerry’s life back to normal, though, for one of Domenici’s lieutenants is looking to betray his boss in exchange for favors from Leggetti, and he figures the best way to do so is to make sure Jerry loses the final fight at Battle Creek, one way or another.

So what is it that leads me to have such fondness for a movie that attracted little but scorn when it was new? In a contortion of taste that would probably be surprising if it were anybody but me talking, it is precisely the compromise at the core of The Big Brawl that I find gives it most of its charm. It seems to me that this movie’s fight sequences represent a nearly perfect blend of the Eastern and Western traditions. Like most American martial arts movies, The Big Brawl pits one man with a mastery of advanced fighting techniques against a slew of men whose only training comes from handing out back-alley beat-downs. But in marked contrast to, say, your average Chuck Norris movie, The Big Brawl uses the fast pace and elaborate choreography familiar from Hong Kong action films, together with Jackie Chan's trademark “pick up whatever happens to be handy and use it as an improvised weapon” fighting style. The initial battle between Jerry and the gangsters sets the tone for most of the big set-pieces, the only exception being the purely Hong Kong-style face-off between Jerry and the two Cantonese assassins.

Beyond that, Robert Clouse does a surprisingly good job of keeping in mind that The Big Brawl isn’t Enter the Dragon, and that Jackie Chan isn’t Bruce Lee. True, there are a few scenes that flirt with the “next Bruce Lee” folly that nearly killed Chan’s career in the cradle, but Clouse never lets them get out of hand. Nor does he make the mistake of insisting that Chan play the movie straight, and the final showdown between Jerry and Billy Kiss ends up looking as much like a balletically complex slapstick routine as it does like a no-quarter street brawl. This is doubly important because the movie’s storyline is so wacky that it could never work if forced into the deadly serious mood of a Bruce Lee film. There’s an extended, 70’s-style roller derby scene, for the love of God— in a movie that’s supposed to take place sometime around 1930! So it’s a good thing Clouse mostly trusted Chan’s instincts, and let him do what he does best.

That said, there are still a few serious missteps along the way. There are plenty of little lapses of logic, like the fact that the son of an immigrant restaurant-owner somehow has the resources to travel three quarters of the way across a continent to pick up a girl at the dockside, but I’m willing to forgive those on the grounds that it doesn’t often pay to demand seamless plotting from a comedy. Far more serious, however, are the times when the movie doesn’t follow through on a joke for which it has laid considerable groundwork. The most striking example concerns the hooker Domenici sends back to Chicago with Jerry in Mae’s place. With all the time The Big Brawl devotes to setting this plot point up, you’d expect it to have a major impact on the film. But instead, Jerry’s family (apart from Uncle Herbert) vanish almost completely after he resolves to cooperate with the gangsters. The upshot is that a whole movie’s worth of rich comedic material (even the “Saturday Night Live” writers could come up with a funny sketch on the premise of a young Chinese doctor who doesn’t realize his mail-order bride from the old country has been replaced by a mafia-employed whore!) goes entirely unused. Fortunately, there’s enough solid action to cover for the shortcomings of the comedy, just as there’s enough solid comedy to cover for the occasional weakness in the action.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact