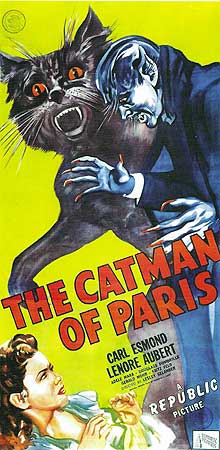

The Catman of Paris (1946) -***

The Catman of Paris (1946) -***

Oh, man… What gets into people sometimes? I seriously expected The Face of Marble to retain indefinitely its championship belt as the screwiest “toss a bunch of unrelated ideas into the crock pot, and hope they all jell together” horror movie of the 1940’s. The Catman of Paris seizes the title handily, however. What looks at first like a late-to-the-party cash-in on The Wolf Man and Cat People wanders steadily farther afield from lycanthropy over the course of its 62 minutes, eventually encompassing gaslighting, astrology, reincarnation, a thinly veiled version of the Dreyfus Affair, and even a few action tropes from B-Westerns. Just like Monogram, Republic Pictures made sure their last fright film of the decade was one to remember!

Author Charles Regnier (From the Earth to the Moon’s Carl Esmond) returns to Paris after two years abroad in Africa and Asia with his friend and literary agent Henri Bouchard (Douglass Dumbrille, of The Frozen Ghost and The Cat Creeps). His new novel, Fraudulent Justice, is all anyone wants to talk about, and that unfortunately includes the authorities. You see, the plot of Regnier’s book bears a suspicious resemblance to a 25-year-old scandal surrounding the supposedly secret trial of one Louis Chambret. The proceedings of the Chambret court were ordered sealed for 50 years when the trial was concluded (by which point all the participants should be too dead to be embarrassed by whatever the record shows), yet Fraudulent Justice contains seemingly obvious analogues for situations that Charles could have known about only if he had access to the interdicted court reports. Not only does that cast suspicion on Regnier himself, but it also presents the government with precisely what it hoped to avoid by sweeping the affair under the rug in the first place. There are those in the cabinet who want very badly to have Fraudulent Justice banned and all copies thus far printed destroyed. However, that will first require convincing a new judge (presumably in a new secret proceeding) that Regnier is lying when he protests that his novel came from nowhere outside of his own imagination. To that end, a lawyer by the name of Devereau (Francis McDonald, from Strange Confession and Son of Ali Baba) has been charged with gathering together all the materials related to the Chambret case. It’s more work than you might think, and Devereau is on a very short deadline. Consequently, he’s been working a lot of nights, and it is well after closing time at the archives when he finishes his task at last. No one at the Ministry of Justice ever sees the fruits of Devereau’s labor, however, for he is waylaid and killed on his way over from the archives, and his valise stolen. A funny thing about the attacker— how often do you see a man in an opera cape and top hat leap down from inside a shade tree with an ear-rending “Meow!” and maul someone to death with his bare hands?

Even so, the abruptness with which the prefect of police (Fritz Feld, from The Golem and The Phantom of the Opera) vaults to the conclusion that a were-cat is to blame for the murder is rather shocking. I mean, he didn’t hear that yowl, right? The prefect’s reasoning seems to go something like this: 1. Devereau’s wounds look like something a great cat would leave on the carcass of its prey; 2. Paris is not known to be prowled by any lions, leopards, or tigers; ergo 3. the lawyer must have been killed by a were-cat. Nevertheless, his subordinate, Inspector Severen (Gerald Mohr, of The Angry Red Planet and Terror in the Haunted House), suggests a more conservative interpretation of the evidence. Severen thinks Regnier knew what Devereau was up to at the archives last night, and murdered the lawyer in order to halt the proceedings against his novel. The prefect admits that Severen’s idea has merit, but pushes him to consider the possibility that Regnier killed Devereau after turning into a cat. Either way, the prefect believes there’s insufficient evidence as yet to support arresting Regnier, but he does authorize Severen to bring him in for questioning as a material witness.

As it happens, there’s a decent enough case to be made for Regnier as the culprit. That getup the were-cat had on when he jumped out of the tree was indistinguishable from what Charles was wearing last night when he and Bouchard went to take in the cancan show at the Café Du Bois. Also, we know that Regnier was taken ill and left the café early, alone. And most curiously, we saw how director Lesley Selander chose to represent a second spell of wooziness that came over Charles on his way home— a weird, subjective image collage printed mostly in negative, including a field of windswept grass as seen from above, a dusty desert landscape, a moonlit and lightning-streaked sky, a buoy lashed by breakers, and finally a closeup on the face of a black kitten. Obviously significant, no? Then when Regnier obeys his summons to the police station, he’s still wearing his tux from the night before, indicating that he never went home to sleep. He has to admit as much, too, because Severen is observant enough to recognize that nobody wears a fucking tuxedo at 9:00 in the morning or whatever. The most damning detail of all, though, is the one Charles doesn’t tell the inspector. Regnier has no memory of the past seven or eight hours whatsoever. It’s all a blur from the moment he left the café until shortly before Severen’s cops came to collect him, and although bouts of amnesia have been a recurrent fact of Regnier’s life ever since he came down with a tropical brain fever during his travels, they’re also consistent with most forms of B-movie lycanthropy.

The Catman strikes again the following evening, once more under circumstances implicating Charles Regnier. He had just gotten finished breaking up with his rich and snooty fiancee, Marguerite Duval (Adele Mara, from The Curse of the Faceless Man and The Vampire’s Ghost), when he was overcome much as before with a fit of negative-printed stock footage, and felt compelled to leave the premises. Marguerite went looking for him in her carriage, found someone dressed exactly like him in a park, and was killed when she invited the latter man aboard for a ride home. Word of the second killing travels fast thanks to a gossip-prone newspaper writer, and Charles is forced to fight his way out of the Café Du Bois in a ludicrous fancy-dress version of a B-Western saloon dustup.

At first, Charles takes refuge with Marie Audet (Lenore Aubert, who met Abbott and Costello while they were meeting Frankenstein and the Killer, Boris Karloff), the daughter of his publisher (Francis Pierlot, from The Man with a Cloak and Bewitched) and the girl for whom he dumped Marguerite. But a high-speed carriage chase against Severen and his cops the following day makes it clear that he needs to get serious about hiding out. Luckily, Bouchard has a friend who is out of the country on business just now, leaving his middle-of-nowhere mansion free for use as a safehouse. By this point, everyone but Marie— Charles included— is convinced that Regnier really is the murderous Catman, and Bouchard begins making arrangements to smuggle him abroad. This, astonishingly, is because Henri considers the lives of a few were-cat victims here and there to be a fair price to pay for Regnier’s literary genius. Regnier himself isn’t so sure about that, but his friends convince him to postpone turning himself in— Bouchard because he’s not done setting up the escape, and Marie because she thinks this whole Catman business is bullshit.

Meanwhile, the prefect of police has called in a humdinger of an outside expert to help Severen with the Catman case. The old man is a professor named de Roche (Maurice Cass), and he brings with him his grandfather’s book, Astrological Prognostications. Among other things, this learned tome tracks through history the appearances of the Catman, which occur whenever Jupiter comes into juxtaposition with the constellation Omnis Magna. (“The Great Everything?” I’m no astronomer— nor astrologer either— but I’d be very surprised to learn that there really is a constellation called the Great Everything.) He first showed up in Rome during the reign of Nero, in time to witness the persecution of the early Christian martyrs. 300 years later, when Julian the Apostate briefly reinstated paganism as the official religion of the Empire, the Catman returned to haunt the Balkans. He was seen in Alexandria as if in celebration of Muhammad’s birth, and in Russia to mark the coronation of Ivan the Terrible. Eight times in all the Catman has visited his depredations on humanity, and if Grandpappy de Roche is to be believed, he’s due for his ninth incarnation— his ninth life, nudge-nudge-wink-wink-saynomore— right about now. Severen is unimpressed, and I’m sure he’d be even more so if he were standing over by the camera, from which vantage point it’s plain to see that the pages of de Roche’s book are all completely blank. But more than that, it’s an awful lot of bullshit to drop on him and the audience both at a time when the climax ought to be right at hand. There’s a good reason for it, though— or as good a reason, at any rate, as anything else in this movie can lay claim to. Charles is being set up, you see, and if he isn’t the Catman, then we need some new explanation to take over for the tropical brain fever which the real culprit obviously would not have had. Mind you, that’s only the beginning of what now has to be re-explained, so I hope you’re in the mood to hear a were-cat’s deathbed confession.

Even said confession leaves us in the dark on one rather important point, which frankly can’t be explained under the conditions The Catman of Paris has set for itself. Go have another look at the litany of historical events for which the Catman served as harbinger. Notice that they’re all calamities, or at least things that bigoted-ass Americans of 1946 would have seen as calamities. So what big-deal disaster is the Catman supposed to be harbinging now? Imagine it as a timeline in a history book: 64 AD— thousands are slaughtered with inimitable Roman ingenuity for refusing to honor the traditional gods; 360 AD— the Christianization of Europe hits a snag when the new emperor orders a return to the religion of old; 571 AD— the founder of Christianity’s greatest rival for the spiritual allegiance of humanity is born in Mecca; 1547 AD— the second-most evil ruler in Russia’s notoriously troubled history ascends to the throne; 1895 AD— some insignificant French twat writes a novel the authorities don’t like. I’m sure it must be hard to keep coming up with dooms to portend century after century— especially if you’re tied to one particular stellar convergence all the time— but surely Catman IX could have found something a little more earth-shaking than that?!

The Catman of Paris is a film whose badness sneaks up on you. Not that it ever looks likely to be good, you understand, but for the first fifteen or twenty minutes, it seems like a fairly unexceptional 1940’s programmer. It’s got clunky dialogue that works out to about 80% artless exposition. It’s got a baffling array of accents, from genuine French to counterfeit French both good and bad to “Fuck it— no one’s going to buy me as anything but an American anyway.” It’s got Belle Epoque hairdos scraped unpersuasively together with half the length of wig necessary to make them work. It has the characteristic second-feature rush to get the story underway before the first reel is used up, even if that means abandoning any pretense to narrative logic or behavioral plausibility. But then unexpected things start happening— things more ridiculous than can be accounted for by shortness of time or money alone. Like the specific images that pass through Regnier’s mind when he goes into one of his fever-fugues— what the fuck are those about? Or the John Ford fisticuffs in what’s supposed to be a genteel Paris night spot, or the Warner Brothers police chase staged with 1890’s carriages, or the prefect of police who acts like he’s been waiting his whole career for a case of lycanthropy. By the time de Roche shows up, you’ll be practically salivating over what idiocy the filmmakers have in store for you next.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact