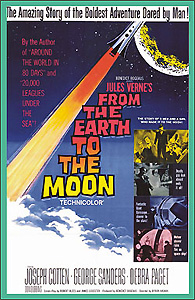

From the Earth to the Moon (1958) *

From the Earth to the Moon (1958) *

Jesus! Somebody please stop me the next time I get it into my head to watch a fucking Jules Verne adaptation! (Unless, of course, it’s also one of the movies that Ray Harryhausen did the effects for... that’s another matter altogether.) From the Earth to the Moon is one of the earliest salvos in the great Verne/Wells fusillade that so defined Hollywood sci-fi in the early 1960’s, and there’s a good chance it’s also the hardest of the bunch to sit through.

Bear with me if this doesn’t make a whole lot of sense— this movie had me bewildered from the word go. One night in 1868, armaments manufacturer Victor Barbicane (Joseph Cotten, from Soylent Green and The Abominable Dr. Phibes) returns to his old home somewhere in the New York hinterland to preside over what amounts to an international meeting of the military-industrial complex. Profits have been running a little thin in the weapons industry ever since the end of the American Civil War (it’s hard to imagine why, what with the Austro-Prussian War in 1866 and the big military buildup that preceded its sequel, the Franco-Prussian War, which would be starting in two years’ time, but, hey— I’ll take their word for it), and Barbicane thinks he’s come up with something that will re-stimulate them. He has developed a new explosive which he calls “Power X,” of such incredible destructive force that a single projectile filled with it will be able to level an entire city. In fact, Power X could potentially even destroy the world! Barbicane’s friends love it.

The only problem is that such a deadly explosive is really too dangerous to test anywhere in the world. Barbicane’s got an answer to that, too: he’ll test Power X on the moon. How? Simple. Build a giant cannon, designed to use Power X as a propellant, and use it to shoot a Power X shell at the moon. Barbicane and his buddies will know if it works because so powerful an explosion will be visible on Earth through any halfway decent telescope. All Barbicane needs now is a whole shitload of money, for which he proceeds to hit up all of his guests.

Meanwhile, down South, Barbicane’s most bitter enemy, another armorer named Stuyvesant Nicholl (George Sanders, from Psychomania and Village of the Damned), is brooding over his biggest reverse at Barbicane’s hands. Nicholl, you see, had been the primary weapons manufacturer for the Confederacy, while Barbicane had armed the Union. Well, we all know how that little contest turned out, and Nicholl seems to have taken the outcome very personally. In fact, he’s gone so far as to challenge Barbicane to a duel. Barbicane, though, has better things to do than trade pistol shots with Nicholl; he’s busy laying the groundwork for shooting his Power X projectile at the moon. And when word of the Northerner’s current project reaches Nicholl, he goes more or less apeshit, ranting about how Barbicane is the next best thing to the devil himself, and how he’s out to destroy the world. In order to nip Barbicane’s project in the bud, Nicholl challenges him to a different sort of contest, one that is not predicated on both parties accepting outmoded Southern ideas of manly honor. He bets Barbicane $100,000 that his new steel-ceramic armor can stop a Power X cannonball, calling into question the entire rationale for the moon-shot program. Barbicane has little choice but to accept.

The contest goes about as well for Nicholl as the Civil War did. After Nicholl sets up an enormous plate of his armor in front of a remote hillside, Barbicane wheels in this cheesy little 3-inch brass muzzle-loader, loads it up, and then tells all the assembled spectators— Nicholl and himself included— to retreat to a bunker he has ordered constructed nearby for just this purpose. Nicholl scoffs, but when he, his daughter Virginia (Debra Paget, from The Haunted Palace and The Most Dangerous Man Alive), and the other spectators emerge to see what happened, not only is his armor plate no longer anywhere to be seen, but the entire hillside behind it has been reduced to ash. After that little demonstration, Barbicane has every defense contractor in the world lining up to front him money for the moon-shot.

The governments of the world are a bit less eager, though. Barbicane gets a telegram from the president of the United States (Morris Ankrum, of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and Giant from the Unknown), urging the armorer to meet him for an important discussion. It seems the international community has decided that Barbicane is secretly getting his money from Uncle Sam, and that the whole Power X program is really a bid by the US to rule the world. As such, 22 nations have sent word to the president that they will consider it an act of war if Barbicane’s moon-shot goes ahead as planned. The president doesn’t want to tell Barbicane not to fire off his cannon, but he urges him not to load it with any Power X— let the rest of the world think the experiment was a flop, and the whole furor should blow over in short order. But whatever Barbicane decides to do, he must under no circumstances let on that he ever met with the president; that would surely be taken as confirmation that the government had been backing him all along. Barbicane hates the idea— it’ll ruin his reputation, and put him in seriously hot water with his creditors— but he agrees to cancel his project. Sure enough, Barbicane becomes the most hated man in the world. The other arms manufacturers believe he’s swindled them, and huge mobs choke the streets calling for his blood in every major city in the Western world. Nicholl, as you might imagine, is delighted.

But it’s hard to keep a good war profiteer down, and the examination of something he found in the rubble at the site of his contest with Nicholl soon gives Barbicane the idea for a new spectacular stunt with which to prove the efficacy of his Power X. He’ll still be using it to lob a projectile at the moon, but rather than a Power X warhead, this shell will be carrying him! The object he brought back from the test site was a small, charred fragment of Nicholl’s armor, and a chemical examination of it reveals that, while it’s no match for Power X, it will serve perfectly well to shield an object from the heat of reentry. If Barbicane can convince Nicholl to team up with him, he’ll be able to build a spacecraft that can get to the moon, come back, and land safely on Earth. After much show of resistance, Nicholl agrees to the partnership, and within days, he, Barbicane, and Barbicane’s assistant Ben Sharpe (The Illustrated Man’s Don Dubbins) are hard at work on the shell/spacecraft while another arms dealer named Von Metz (Ludwig Stossel, from Bluebeard and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse) gets moving on constructing the cannon that will fire it.

Naturally, all does not go according to plan. First, Virginia has fallen in love with Ben, and she stows away on the Columbia (as the space capsule has been dubbed) so that she might be with him in the event that he fails to return alive. Then it turns out that Nicholl has forgotten none of his bitterness against Barbicane, nor his crusading zeal to protect the world from Power X. Nicholl has sabotaged the Columbia so that its sustainer rockets won’t fire in the proper sequence, burning up all their fuel long before they reach the moon. Nicholl, of course, hadn’t figured on Virginia sneaking aboard, nor had he appreciated the potential peacetime application of Power X as an energy source, or its peacekeeping potential as an instrument of mutually assured destruction. The rest of the film concerns the efforts of the Columbia crew to salvage the situation and get back to Earth safely.

This has got to be the most illogical major-studio science fiction movie I’ve ever seen. Let’s begin at the beginning, shall we? The whole rationale behind Barbicane’s moon-shot is that Power X (which, you’ve probably figured out by now, is supposed to be atomic fission) is too dangerous to experiment with on Earth. Well, if that’s so, then wouldn’t it be equally unsafe to use it as the propellant in the cannon to shoot the Power X shell to the moon? Wouldn’t it make much more sense to experiment with tiny quantities of the stuff under controlled conditions— in fact, isn’t that pretty much exactly what Barbicane does when he uses Power X to destroy Nicholl’s snazzy armor plate? For that matter, why follow through on the moon-shot at all after that little demonstration? The outcome of the Nicholl challenge proves Power X’s effectiveness all by itself! The reasoning behind Barbicane’s recasting of his mission also escapes me. If the other nations of the world considered Barbicane’s Power X test tantamount to an act of war by the United States because they feared the fallout of an American Power X monopoly, then why does it bother those governments any less for Barbicane to shoot himself to the moon instead of an artillery shell? He’s still experimenting with Power X, you know! And while I’m on the subject of international reaction to Barbicane’s work, what possible reason could there be for rioting in the streets in response to his calling the program off?!?! I realize that things were very different in 1958, but can you honestly imagine thousands of people thronging the streets of the world’s cities to protest the cessation of nuclear weapons experiments?! Neither can I. I will say one thing for From the Earth to the Moon, however: I can honestly say that this is the only movie I’ve ever seen that took such a positive view of war profiteers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact