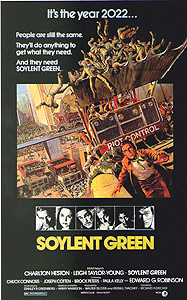

Soylent Green (1973) **½

Soylent Green (1973) **½

Together with Silent Running, Soylent Green would make an excellent introduction to early-1970’s polemical sci-fi. Like that earlier film, it is loaded with interesting ideas that manage to be simultaneously incompletely formed and wildly overwrought, all of them delivered with a desperate earnestness that is ultimately self-defeating. Again and again, it threatens to become almost brilliant but then spirals frantically out of control, often leaving its audience more amused than moved. But beyond all the similarities of tone and perspective, Soylent Green reminds me of Silent Running in that it begins by facing up to an issue that the latter movie skirted to its great detriment: in a future characterized by worldwide ecological collapse, what on Earth are we going to eat?

In the year 2022, human overpopulation has reached such desperate proportions that New York City struggles to accommodate a population of 40,000,000 people, nearly half of them effectively homeless and/or out of work. The rampant inflation of the 70’s has apparently continued unchecked, atmospheric pollution has radically altered the planet’s climate, and infrastructure decay has reached such a pace that virtually nothing in any of the major cities can be kept in proper working order. But perhaps even worse than any of these scourges is their cumulative effect upon American society. Overpopulation has created an environment in which the life of the average person is all but worthless. There is no such thing as job security anymore, class stratification has intensified to positively medieval levels, and the constant struggle for bare survival on the part of hundreds of millions of economically superfluous people has undermined whatever traditional notions of morality were left standing after the great social transformations of the 60’s and 70’s. A tiny minority of the super-rich live like omnipotent hereditary nobility, wantonly consuming hundreds of times their fare share of the planet’s dwindling resources, maintaining their mid-20th-century standards of living while the great bulk of their fellow men and women lack running water, reliable electricity, or sufficient dwelling space to live like human beings. And naturally, only the rich are able to afford what we think of today as food. With strawberries going for $150 a jar and meat a rare luxury even for the upper crust, the basic nutritional needs of most Americans are met by the products of the Soylent Corporation. Soylent Yellow, the oldest of the company’s three flagship foodstuffs, is an unpalatable paste made from soybean concentrate; it’s high in protein and a diet based on it will keep you alive and more or less healthy, but it isn’t something you’d eat if you had much choice in the matter. Soylent Red is rather less nasty. Another soy product, it is versatile enough that it can be made into passable approximations of most grain-based foods, and unlike Soylent Yellow, it can be described with a straight face as having a flavor. But the masses’ current favorite is the new Soylent Green. With Green, the Soylent Corporation has branched out a bit, turning, according to its advertising literature, to the vastness of the oceans for its raw materials— whereas Soylents Yellow and Red are soybean derivatives, Soylent Green is made from oceanic plankton, the closest thing to an infinite nutritional resource that the hard-pressed Earth still has to offer. Unfortunately, the very newness of Soylent Green means that it is in chronically short supply, despite the nearly limitless quantities in which it should theoretically be available; Soylent’s factories simply aren’t yet able to match the supply of Soylent Green to the public’s insatiable demand.

This is the world in which police detective Robert Thorn (Charlton Heston, from The Naked Jungle and The Omega Man) lives. Thorn is part of what remains of America’s working class, and as such he lives in a tiny, dingy apartment with his partner, Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson). Roth is, in the parlance of 2022, Thorn’s “book.” Global deforestation has rendered trees too scarce to be used for such frivolities as printing paper, and thus very few real books are published anymore. Most people are understandably just barely literate these days, and to compensate, the New York Police Department teams its detectives in the field with highly educated men of phenomenal memory capacity to handle the documentary investigation and research that most of the front-line cops are now incapable of doing for themselves. When we meet the two men, they are grappling with a slate of confusing cases, on which their lack of tangible progress has put both their jobs on the line. They’re about to get handed an even tougher one.

At the other end of the social ladder stands William R. Simonson (Joseph Cotten, from Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte and Baron Blood), an executive of the Soylent Corporation. One night, a young man enters Simonson’s hyper-luxury apartment in Century Towers while his bodyguard, Tab Fielding (Chuck Connors, of Tourist Trap and “Werewolf”), and his “furniture,” Shirl (Looker’s Leigh Taylor-Young), are out. (An aside: The notion of “furniture” is probably my favorite aspect of Soylent Green’s vision of the future. In an especially stark illustration of the devaluation of human life, wealthy men like Simonson often rent their dwellings “furnished” with attractive young women who serve as both domestic help and sex objects. The economy is apparently so wretched that a woman with the allure to succeed as furniture counts herself among the privileged few.) The prowler catches Simonson in his living room, and after a brief talk (over the course of which it becomes clear both that Simonson knows the other man has been sent to kill him, and that the doomed exec agrees that his death is necessary morally as well as pragmatically) staves Simonson’s head in with a crowbar. Thorn ends up assigned by his superior, Lieutenant Hatcher (Brock Peters, from Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off and Alligator II: The Mutation), to investigate the slaying, sending him off on a path that will eventually lead him to discover that the world is an even worse place than it looks on the surface.

Thorn almost immediately realizes that Simonson was assassinated, rather than killed during a routine burglary attempt, as the circumstantial evidence would initially seem to suggest. The deeper he digs, the more it looks like Simonson was eliminated on the orders of his superiors within the Soylent Corporation, the leadership of which seems to be conspiring with the government to conceal some sort of terrible secret. While Thorn is out following up such leads as he can find with a truly stunning lack of success (mostly he just beats up Tab Fielding and spends a whole lot of time in bed with Shirl), it is Roth who uncovers the truth. Some company reports found in Simonson’s apartment, combined with other documents in the possession of the Supreme Exchange (a sort of central library for use by Roth and his fellow books), point almost irrefutably to the conclusion that the Soylent Corporation has secretly undertaken to solve America’s food problems in the most ruthlessly practical way imaginable. The primary ingredient of Soylent Green, as pretty much everybody who knows anyone who watches “Saturday Night Live” is aware by now, is not oceanic plankton but human flesh. The knowledge of this ultimate betrayal of the 20th-century morals the aged Sol still holds dear is enough to drive the old man to kill himself in one of the city’s suicide parlors, but he passes on what he has learned to Thorn before he goes, and the younger cop sees the ugly truth for himself when he surreptitiously follows the progress of his partner’s body through the innards of the waste processing center to which the death shop sends its satisfied customers. The movie ends with Thorn telling his story to a highly skeptical Lieutenant Hatcher after a closely contested shootout with the waste plant’s guards.

Silent Running isn’t the only piece of polemical fiction that Soylent Green reminds me of. It also had me thinking of a novel called What Is to Be Done?, by the early Russian communist author Nikolai Chernyshevsky. Both works are nominal detective stories whose creators cared not one whit about the puzzles their characters were trying to solve, concentrating instead upon depicting the awfulness of the world in which those characters were forced to live. The object, of course, was to issue a rallying cry for the destruction of that world (What Is to Be Done?) or for changes in the way real people live that would prevent such a world from ever coming into existence (Soylent Green). In both cases, the central aim is hampered because this just isn’t a terribly effective way of making a point. Chernyshevsky had a good excuse for sneaking his politics in through the back door, in that he wrote What Is to Be Done? while he was already in prison for making inflammatory statements against the czar and his regime. But the makers of Soylent Green had no such hurdle to overcome, and would have done far better to follow the lead of Upton Sinclair or George Orwell by using the central narrative itself to score most of their rhetorical points. As it is, director Richard Fleischer and screenwriter Stanley R. Greenberg allow their lack of interest in the main plot to infect the audience as well. It’s awfully hard to care much about a detective story in which the main detective just kind of wanders around ineffectually for an hour and a half before being handed the answer by his partner, who had it handed to him in turn by a bunch of characters we’ve never even seen before and won’t be seeing again. The details we pick up along the way about life in New York in 2022 are often impressively insightful, reflecting far more than the usual degree of effort invested in making a dystopian world believable, but even here the filmmakers do themselves a disservice by setting the story near enough to what was then the present day that it becomes hard to swallow both the sheer magnitude of the breakdown and the quiescent acceptance of the way things are on the part of everybody but Sol Roth— surely Sol isn’t the only person Thorn or Hatcher or Shirl has met who remembers how the world used to be?! Then of course there’s the simple fact that the world’s economy and ecology have proven to be far more complicated than anyone seemed to realize in the early 1970’s. For example, who would have imagined, in the days when The Population Bomb was on the bestseller list, that much of the developed world would be threatened by population implosion only 25 years later, even as Africa and mainland Asia continue to produce more people than they can realistically support? The confounding complexity and flexibility that the world has exhibited since those seemingly apocalyptic years between the Summer of Love and the end of the Cold War would tend to make Soylent Green look hysterically shrill in its outlook even if it had been as coherent as it should have.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact