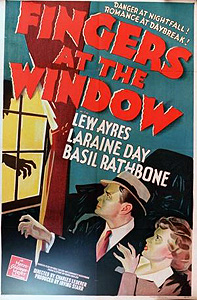

Fingers at the Window (1942) *½

Fingers at the Window (1942) *½

I don’t really know what to make of Fingers at the Window. My first impression was something to the effect of, “Holy shit! I didn't know MGM made Val Lewton rip-offs!” But then I noticed the movie’s release date, and I’m not so sure anymore. Fingers at the Window sure does look like an effort by MGM to make a cheap psychological horror flick of the sort that Lewton was producing for RKO in the early-to-mid-1940’s, but by 1942, only one of those films had seen release. What’s more, since I don’t know quite when in 1942 Cat People hit the theaters (or Fingers at the Window either, for that matter), I also have to consider the possibility that this movie actually predates even the earliest of what would otherwise seem to have been its models. One thing is certain, though. If MGM were trying to copy Lewton, they got it just as far wrong as Universal did when the latter studio answered Cat People with Captive Wild Woman, though their missteps were in a totally different direction.

What Fingers at the Window really feels like— and what it might really be, at that— is a throwback to the kind of horror movies Warner Brothers and First National were making at the beginning of the preceding decade. Certainly the basic premise is at least as ghoulish as anything in Doctor X or The Mystery of the Wax Museum— for some reason, Chicago is in the midst of an epidemic of axe murders! Mind you, this is not the work of some psycho on a killing spree. Rather, on five separate occasions, somebody has wigged out for no apparent reason, and hacked a total stranger to death with an axe. The killers then lapse into a catatonic state, and are thus unable to provide any kind of clue as to what led them to kill, or why they picked the specific victims they did. Police Inspector Gallagher (Charles D. Brown) is at his wits’ end, and calling in the assistance of a psychiatrist named Dr. Cromwall (The Invisible Ray’s Walter Kingsford) hasn’t really done him any good as yet.

Meanwhile, Oliver Duffy (Lew Ayers, later of Donvan’s Brain and Salem’s Lot) is about to become a living cliche, an out-of-work actor. The theater troupe of which he is a part hasn’t been doing very well lately, and the head of the company thinks it’s about time to cut his losses and call a quits. Perhaps they’ll move on and try their luck in New York, but even that prospect is far from certain. On his way home from his last night on the job, Duffy notices that somebody is following a young woman (Larraine Day, who played opposite Ayers in the ridiculous profusion of Dr. Kildare movies during the three years prior to Fingers at the Window) at a suspiciously discreet distance, with something (an axe, maybe?) concealed beneath his coat. Oliver hurries ahead to warn the woman of her danger, but because her pursuer is hiding behind a corner when she scans the street for him at Duffy’s direction, she assumes the actor is just some scumball trying to take advantage of the current panic to find his way between legs that would normally be closed to him. When Duffy hustles Miss Edwina Brown over to a patrolling cop, she reports him, and then goes along her way. Obviously this girl does not deserve her luck. Duffy is still in the area when the man with the axe catches up to her, and he responds to her screams quickly enough to chase the would-be killer away.

At least Edwina is a bit friendlier now. She permits Oliver to walk her home, and when the hallway light in her apartment building proves to be burned out, she even invites him up to her tenement. The two get to talking (about his fizzling acting career, about her rather more successful one as a dancer, about the couple of years she spent in Paris), and Duffy is up there with her long enough for him to notice that somebody keeps peering in Edwina’s bedroom window from the fire escape outside. He doesn’t say anything about it to her, but that night he beds down on the grating right outside the girl’s apartment, so that he’ll be handy in the event that she should need another rescue.

At the same time, we’re starting to see that there’s more to this axe-murder business than meets the eye. Somebody is leading feebleminded men around town, telling them how much they hate certain specific people (Edwina Brown, for instance), and suggesting that the most elegant solution to their problems is to kill the object of their supposed hatred with an axe. We don’t get to see the face of this criminal mastermind, but his voice is one that most fans of 40’s horror cinema will recognize almost immediately as that of Basil Rathbone (from Tower of London and Son of Frankenstein).

Evidently there was more than one axe-man on the prowl that night, because the morning papers all proclaim that the body count is now up to six, even though Edwina is still safe and sound and looking forward to her upcoming dinner date with Oliver. The date doesn’t come together, though, because of something Oliver noticed when he woke up out on the fire escape, which he thinks merits far more of Miss Brown’s attention than a nascent romance. Somebody came along while he was sleeping, and unscrewed the latch on her bedroom window. With that in mind, the couple spend their evening together planning an ambush for the armed lunatic they know will be dropping in sooner or later. And when they catch him, it’s the same old story; the axe-man goes into catatonic shock even before the police have him in custody.

Having just accomplished more in regard to the mysterious murder epidemic than the police have managed since the killings began, the rather egotistical Duffy gets it into his head that he ought to be able to crack the case altogether. And to be fair, he does have one legitimate clue to start from. The doggedness of the psycho’s efforts to kill Edwina suggests more than just a sudden outburst of homicidal rage. Duffy’s theory that there is intelligent design behind the killings is further bolstered when a second maniac comes after Edwina in the hotel where the police have put her for the sake of keeping their star witness safe from harm. Gallagher rejects Duffy’s claims that the police should be looking for some kind of diabolical genius, though, and that means that the actor-turned-sleuth is entirely on his own. In fact, he’s doubly so, for although it soon becomes quite obvious that some sort of connection exists between the axe murders and something that happened to Edwina in Paris, the girl stubbornly refuses to give Oliver the details he needs to figure out what that connection is. This, even though Edwina’s life is plainly at stake! So when Duffy’s investigations eventually lead him into contact with a psychiatrist named Santell, and when Santell turns out to be played by Basil Rathbone, Oliver is unable to make the intuitive leap that we do instantaneously. That inability will nearly cost Duffy his life before this is all over, while some of the more ill-advised tactics he pursues while digging up the dirt on the killings will have the effect of convincing Gallagher that Oliver himself is most likely calling the shots on the axe murderers. Of course, this being 1942, the movie can only possibly conclude with Edwina sinking into Oliver’s arms in a hasty happy ending, but there’ll be some awfully close calls for both characters along the way.

So who remembers what bothered me most about Doctor X and The Mystery of the Wax Museum, to which I compared Fingers at the Window earlier? That’s right, it was their consolidation of hero and comic relief in a single character. And who remembers what I keep harping on whenever the subject of old MGM horror movies comes up? That’s right, it’s that studio’s chronic, neurotic reluctance to let a horror movie be a horror movie, and go for the throat. Well in Fingers at the Window, we have both of those annoying qualities in action at once. Lew Ayres goes through the movie like that kid in your third grade class who just couldn’t help himself from turning everything that the teacher (or anyone else) said into a joke, and his shtick has already gotten old by the time it becomes clear that he’s going to be the male lead. What’s more, though Oliver Duffy is undoubtedly supposed to come across as a loveable rogue, he’s really just an asshole, and if you’re anything like me, it’s going to make you mad that Inspector Gallagher (whom we’re not really supposed to like) is the only person who figures that out. Then again, Duffy’s offhand remark at one point that Edwina Brown “hasn’t got the brains of a pancake” marks him as the only one who sees her as she really is. So I suppose we can at least say that the two of them probably deserve each other: the Asshole and the Numbskull, a match made in Heaven.

On top of all that, Fingers at the Window features what may just be the laziest writing in any MGM horror flick. Where this really comes to the fore is in the character of Dr. Santell. Considering that his mysterious vendetta against Edwina Brown and the six others his remote-control maniacs go after is the mainspring of the entire plot, you might expect screenwriters Lawrence P. Bachmann and Rose Caylor to have given at least a little bit of thought to the question of how he engineers these crimes. Since it eventually comes out that not only is Santell no longer practicing, he was never really a credentialed psychiatrist in the first place, he obviously can’t be recruiting his soft-headed hit-men from the ranks of his own patients. Nor is there any indication that he’s a hypnotist, or possessed of telepathic powers. People apparently turn into axe murderers on his say-so, just because he says so. It’s the kind of thing that hardly any movie could get away with, and coming on top of everything else that’s wrong with Fingers at the Window, it’s really the last straw.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact