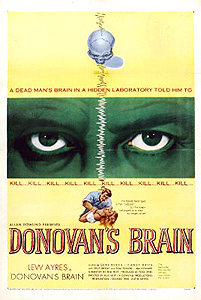

Donovan’s Brain (1953) ***½

Donovan’s Brain (1953) ***½

Back in my review of The Ape, I lamented the sad state of the old-fashioned gorilla movie in present-day filmmaking. Gorilla movies aren’t the only traditional exploitation subgenre we’re in danger of losing, though. Cannibal movies died outright in the mid-80’s; sword-and-sandal has been relegated to TV, where it is mostly defined by the now-defunct “Hercules: The Legendary Journeys” and “Xena: The Warrior Princess;” gut-munching zombies and women in prison are in such pitiful decline that they can only be found in the direct-to-video market these days, and rarely even there. And hell, I can’t even remember the last time I came across a new lesbian vampire flick! There’s another category, too, that has fallen by the wayside, and did it so quietly that most of us probably never even realized it was gone. I’m talking about the venerable Brain Movie.

Brain Movies appeared for the first time back in the 1940’s, and the subgenre managed to cling to life until at least 1988, the year of The Brain. But it was during the 50’s that the Brain Movie really hit its stride, and the defining moment in the subgenre’s history seems to have been the release of Donovan’s Brain, still one of the best films of its type more than half a century later. This was the second and most successful of the three movies based on Curt Siodmak’s novel of the same name, which had been filmed in the 40’s as The Lady and the Monster, and which would be remade again in Germany a decade later as The Brain (not to be confused with the Canadian film of the same title from the late 80’s). From what I’ve read about the novel and the other two film versions, this would seem to be the most faithful of the screen adaptations, although it certainly diverges from Siodmak’s story in a number of predictable ways. With a 1953 release date, for example, it should be obvious that some of the more quasi-mystical elements of the novel would be jettisoned, and given that this is Hollywood we’re dealing with, the main character is going to need a love interest in his life.

That main character is a medical researcher named Dr. Patrick Corey (Lew Ayers, later of Damien: The Omen II and Battle for the Planet of the Apes), and the love interest is his wife, Janice (Nancy Davis, better known these days as Mrs. Just Say No herself, Nancy Reagan). Corey and his alcoholic town-doctor friend, Frank Schratt (Gene Evans, from Shock Corridor and The Giant Behemoth), are working on a way to keep animal brains alive outside the body, hoping to unlock the secrets of their physiology in a time before non-invasive means for looking inside the skull had been invented. Just as Corey and Schratt achieve their first real success with a monkey’s brain, Corey receives a phone call at his house from Police Chief Tuttle (James Anderson, of The Thing that Couldn’t Die and I Married a Monster from Outer Space). Tuttle is looking for Schratt; there’s been a plane crash just outside of town, and some of the small aircraft’s four passengers might still be alive.

As it turns out, only one of them is, and he— tycoon Warren H. Donovan— probably won’t be for much longer. The crash has reduced Donovan’s legs to strips of tattered meat, and he’s suffered grievous injuries to his upper body as well. The hospital is too far away from the crash site, but because Corey’s home lab is almost as well equipped and is a hell of a lot closer, there’s still an outside chance for Donovan to pull through. After getting him into the lab, Corey and Schratt work long and hard at saving the wounded man, but in the end, there’s really nothing they can do. Unless... A quick glance at the tank in which he has the monkey brain wired up gives Corey the idea that he could do the same thing with Donovan. Sure, it wouldn’t be quite the same thing as saving his life in the usual sense, and the law would certainly look askance at it if the story ever got out, but Corey correctly reasons that he’s got a once-in-a-lifetime chance here. Donovan is going to die anyway, so it isn’t as though he’ll exactly be needing his brain in the future, and the potential for benefit to humanity is so vast. Schratt and Janice refuse to go along with it, but Corey presses on by himself, and soon Donovan’s brain is sitting in the monkey brain’s old tank, alpha-waving contentedly away.

But the death of a millionaire is rarely a simple matter of signing the certificate and buying the box, and Donovan’s demise proves to be particularly fraught with complications. First of all, the old man left no will, and hadn’t gotten along with the two most likely heirs— his son and daughter— in years. Second, Donovan was embroiled in intractable tax fraud litigation, having spent his entire life doing anything he could, legal or otherwise, to keep the IRS away from his money. Third, Chief Tuttle has it in for Frank Schratt, and would very much like to see the doctor replaced in his position by the policeman’s brother. Tuttle therefore has a reason to peer very closely into the Donovan situation, looking for any irregularities that might serve as a hook on which to hang his brother’s hard-drinking rival. Finally, the commotion attendant on the tycoon’s death has attracted journalists from all over the place, and one of them— a freelancer named Herbie Yocum (Steve Brodie, from The Giant Spider Invasion and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms)— seems likely to make all kinds of trouble for Corey down the road, especially after he finagles his way into the lab and “accidentally” takes a picture of the tank with the stolen brain sitting in it.

All of that pales, however, in comparison to the trouble Corey gets himself into with Donovan himself. Soon after extracting the brain, Corey suddenly realizes that if the thing is alive, it must also be thinking. Corey soon becomes obsessed with the idea of communicating with the disembodied organ, and begins doing extensive biographical research on Donovan in the hope of uncovering anything that might help him make some kind of connection with the brain. Eventually, he seizes upon telepathy, and though it is never really explained how, that proves to be Corey’s golden ticket. One night, Donovan’s brain establishes telepathic contact with Corey’s, and causes the scientist to write himself the message, “Get to N. Fuller— W. H. Donovan,” in handwriting that later proves to be indistinguishable from Donovan’s own.

So who is this N. Fuller? Nathaniel Fuller (Victor Sutherland) was Donovan’s L.A. lawyer, and a few days after receiving his initial message from the brain, Corey finds himself face to face with Fuller, having been pressed into service as a surrogate body for Donovan. Acting under the brain’s control, Corey flies to Los Angeles, rents Donovan’s favorite suite in the Town House hotel, withdraws $27,000 from one of Donovan’s numerous assumed-name bank accounts, and goes to see the lawyer to arrange a meeting the following day between Corey, Fuller, and “Mr. Donovan’s Washington connection.” When Fuller protests that he doesn’t know what Corey is talking about, Corey tells the lawyer that he is in possession of “certain checks” endorsed by both Fuller and the man in Washington, which presumably would place both men in a very awkward position if anyone else were to find out about them. It’s all very mysterious, but it looks like Donovan has decided to get back to his old business, operating under the pretense that he designated Corey as his agent shortly before the accident.

Meanwhile, back on the home front, Janice and Schratt are starting to worry about Corey. They think he’s giving himself some kind of mental collapse with the strain of his round-the-clock work on the care and feeding of Donovan’s brain. They’ve noticed that Corey has begun copying Donovan’s mannerisms— as described in the innumerable magazine and newspaper articles about the man that Corey had read as background research— and they believe he’s now so obsessed with proving the possibility of telepathic communication with the living brain that he subconsciously places himself under some kind of self-hypnosis, in which state he then acts out what he thinks Donovan would do under the circumstances. What finally opens their eyes to the true danger that Corey has put himself in is a brief run-in between Schratt and the brain, in which Schratt actually feels Donovan trying to read his mind. But by this time, Corey has already attracted the attention of the FBI, special investigators from the Treasury department, and Yocum— the latter of whom has come to the conclusion that blackmail could be a far more lucrative occupation than freelance journalism. And the brain, for its part, has become aware of the threat posed to it by Corey’s friends, and has just realized how effective mental domination can be as a means of engineering unfortunate accidents. There’s just one glimmer of hope for Corey, Schratt, and Janice— be it in its body or in a glass tank full of ionized nutrient solution, a brain still needs to sleep once in a while, and Donovan’s access to his victims’ thoughts doesn’t seem to be quite complete.

I wish director/screenwriter Felix Feist had kept Siodmak’s original ending when adapting Donovan’s Brain. I’ve never cared much for the deus ex machina, and the out-of-nowhere, almost accidental-seeming conclusion to this version of the story is especially vexing, in that it is so far beneath the standard set by the rest of the film. I suppose I can understand that the hard-headed, techonphiliac 50’s would have been the wrong time for a movie climax that hinges on a telepathic battle of wills, but it would have been so much more satisfying to watch than what happens here. I’m also a bit ambivalent about the casting of Nancy Davis as Jan. Sure, it’s a gold mine of irony seeing the future Nancy Reagan plodding robotically through the part of the perfect Republican housewife in a slightly tacky movie about an evil tycoon’s undead brain, but she’s jarringly at odds with the overall tenor of the movie, which is serious, competent, and above all intelligent. I’m much happier with Lew Ayers, whose Patrick Corey really does seem like a different person whenever he’s channeling the mind of Warren Donovan. And whatever else you may think, you’ve got to give props to a movie that has the nerve to make an alcoholic doctor one of the good guys without spending a single second of screen time trying to sober him up and “redeem” him. It’s easy to see why the Brain Movie wave crested in the 1950’s; having just seen Donovan’s Brain, I’ve got half a mind to try to make one of the things myself.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact