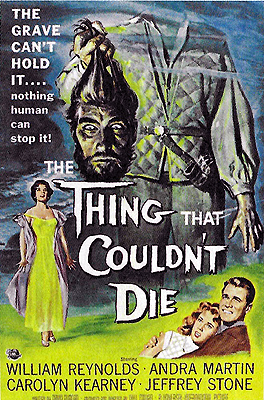

The Thing that Couldn’t Die (1958) ***

The Thing that Couldn’t Die (1958) ***

When the obvious veins of ideas are all mined out, there are really just two ways to go. Either you can keep repeating yourself endlessly, reaping ever smaller returns for the effort, or you can go poking around in little-explored corners, looking for new veins of ideas that don’t immediately suggest themselves. In the world of movies, alas, it’s usually the former strategy that gets put into play, but every once in a while, even the big studios get desperate enough to diverge from the beaten path. For whatever reason, the late 1950’s saw a fairly steady output of arrestingly quirky horror and sci-fi films from Universal. After that studio beat the ideas behind Creature from the Black Lagoon, Tarantula, and their cousins thoroughly to death, they unexpectedly shifted gears and began producing cheaply made but satisfyingly offbeat movies like The Monolith Monsters and Curse of the Undead. 1958’s The Thing that Couldn’t Die was part of this brief outpouring of eccentricity, combining psychic powers, Satanism, and an evil, living mummy head into a flick that is simply too weird to turn away from.

Somewhere in the arid countryside of southern California, eighteen-year-old Jessica Burns (Carolyn Kearney, from Hot Rod Girl and Young and Wild) is doing the old looking-for-water-with-a-forked-stick routine while her aunt, Flavia McIntyre (Peggy Converse), and two handymen look on. Jessica hasn’t had much success by the time her cousin, Gordon Hawthorne (William Reynolds, of The Land Unknown and Cult of the Cobra), comes upon the scene accompanied by Linda Madison (Andra Martin) and Hank Huston (Jeffrey Stone), two friends who have come along on his visit to the old homestead. Gordon is an archaeologist by trade, which makes him more than enough of a scientist to scoff openly at Jessica’s supposed paranormal gifts in that characteristic 50’s way. Nevertheless, Jessica does indeed find what she claims is an underground source of water, and Aunt Flavia soon sets her men to the task of digging a well on the spot. But scarcely has handyman Boyd (I Married a Monster from Outer Space’s James Anderson) taken the first swing with this pickaxe when Jessica abruptly starts shrieking about how they must not dig a well there, because she can sense something evil buried under the ground. No one believes her, of course, any more than they believe it’s her spoiled-teenage-brat rage at that unbelief that brings a big, convenient tree branch down on top of Linda. They don’t buy the bit about an “Eeeeevil wind” blowing down the limb, either.

Jessica’s powers are real, though, and to prove it, she tells Linda later that afternoon that the watch she’s been missing for several days was stolen, but “not by anything human.” Not only that, she even tells Gordon where to look for the watch— at the base of a huge old tree out in the back yard. Sure enough, the watch is there, in a rat’s nest. But, say... what’s that thing in there with it? Why, I do believe it’s an enormous fleur-de-lis pendant! And it must be old, too, because one of the tree’s thicker roots has actually grown through the loop of the chain. Well, Gordon feels so bad about the way he’s been doubting his cousin that he unclasps the chain, and brings the necklace in as a gift for Jessica. All is forgiven, and the signs start pointing toward icky, pederastic cousin-love.

Now about that subterranean evil... The well-digging duties have shifted to Mike (Charles Horvath, a bit player whom we’ve encountered before in The Werewolf and How to Make a Monster), who like two out of every three B-movie handymen is as strong as an ox, but a bit on the dim side. Shortly after nightfall, Mike’s pickaxe strikes some heavy, metallic object buried in the earth; it’s a copper coffer about 18”x12”x15” in size. And as Gordon points out the moment he gets a look at it, its lid bears an inscription in Elizabethan English admonishing whomever finds it to leave it alone if they value their eternal souls. A bit of pondering convinces Gordon that the chest must have been buried by sailors in the employ of Sir Francis Drake, the only Englishman who would have come anywhere near California in the late 1500’s. And if that’s true, Mike’s find is of incalculable value, even above and beyond the monetary worth of whatever happens to be locked inside it. It takes some work to convince Aunt Flavia, but the idea does eventually sink in that the casket might be so valuable as a historical artifact that she’d get far more out of selling the box unopened than she would from peddling its contents. To that end, Gordon heads out to the university where he works to fetch archaeology department chairman Professor Julian Ash (Forrest Lewis, whose career exhibits an odd confluence with that of the band, the Angry Samoans— not only did they write a song about his movie, The Todd Killings, the cover art for their Back from Samoa album comes from The Monster of Piedras Blancas, in which Lewis also appeared). With all the excitement in the air, nobody pays much attention to the hysterical dread with which the antique chest fills Jessica.

They should, though. When everybody goes to bed, Flavia assigns Boyd and Mike to guard the spare room where the casket is being stored temporarily. This is a bad thing, because it has occurred to Boyd that Mike is almost certainly strong enough to pry off the lead bands holding the box shut with his bare hands. Because this will leave the box undamaged, and because nobody has yet seen inside it to know what it contains, Boyd figures he’s got a perfect chance to improve his fortunes by helping himself to a bit of the Spanish colonial treasure that he imagines was buried inside the chest. It doesn’t take much to convince Mike that Flavia has given her blessing to an attempt to open the casket by hand, and the Herculean halfwit has the bands off and the lid up long before Gordon returns with Professor Ash. The only trouble is, there’s no gold inside. All the casket contains is a living, severed head— and a living, severed head with psychic powers, at that! The head seizes control of Mike’s feeble mind, forces him to kill Boyd, and then orders him out into the countryside in pursuit of some nefarious end.

We quickly learn just what that end is, too, courtesy of Jessica’s own psychic abilities. The head belonged to one of Sir Francis Drake’s sailors, a certain Gideon Drew (Robin Hughes, who has a much bigger role here than he had in The Mole People or The Son of Dr. Jekyll). Drew was a Satanist who had traded his soul to the devil for a whole raft of supernatural powers, but Drake caught on to him during a long Pacific cruise in the 1570’s, and brought him ashore to deal with him. The method of Drew’s punishment makes for an interesting twist on the Condemnation to Eternal Unlife theme: his head was severed from his body, but because the terms of his contract with Satan call for his body to be intact at the time of his death, the devil has refused to accept his soul, leaving him trapped in his own lifeless body forever— or at least until his head is reattached.

The ingenious thing about The Thing that Couldn’t Die is that its creators refuse to present us with the straightforward monster rampage that seems sure to follow. Drew deliberately allows Mike to be killed by the police who come racing to the ranch once Boyd’s body is discovered, and then, with no retarded murderers to draw attention to him, he sets about possessing as many of Aunt Flavia’s guests as he can. Linda is the first to come under the spell of the living head, and Hank and even Jessica follow soon thereafter. Drew needs as many agents as he can get, you see, because he has no idea where Drake’s men buried his body (his head went into the ground first). Flavia and her hangers-on make for an especially alluring prospect here because they already want to find Drew’s coffin, which is revealed to be somewhere nearby when Gordon cleans some of the crud off the smaller casket, exposing a second, longer inscription; they figure the big box should be worth even more than the little one. All Drew needs to do is make sure that the folks doing the digging want the coffin for the same reason as he does, which is no stretch at all for a mind-controlling warlock. Jessica proves doubly useful once possessed, because this gives Drew access to the girl’s paranormal homing abilities, which were apparently not part of the package the old wizard bought from Satanco, Inc. back when he was alive in the ordinary sense. There are just two snags with this plan. First, Drew has foolishly possessed Jessica before getting to work on Flavia, Gordon, and Professor Ash, meaning that there will be three clear-headed people around when the girl’s powers find Drew’s coffin. Second, that fleur-de-lis necklace Gordon found belonged to Sir Francis Drake, and it has a talismanic power over the bisected warlock not unlike that which a cross generally holds over a vampire. The only reason Drew was able to possess Jessica at all is because she had previously lent it back to Gordon so that he could make a cast of it for the university. Gordon’s still got the thing on him, and if he figures out what it can do, Gideon Drew is going to have a much bumpier resurrection than he reckoned on.

I love living head movies. Granted, they’re usually not quite as much fun as their brain movie cousins, but they’re still almost always a hoot. The Thing that Couldn’t Die is especially appealing, in that it backs up its kitsch value with an interesting and almost logical story (albeit one that is riddled with historical implausibilities). Satanism, after all, is not a subject that one encounters often in 1950’s monster movies. Particularly noteworthy as an example of the care that went into this admittedly cheap and hurriedly made production (cheap enough, in fact, to recycle most of its score from Creature from the Black Lagoon) is the fact that Gideon Drew never talks until after his head has been put back on his shoulders. Think about it— when have you ever seen a living head flick whose creators remembered that a person needs lungs in order to speak? The severed head effects are a bit too obvious in their execution to be really convincing, but the mummification makeup Robin Hughes wears is very good, coming as close as the budget would allow to what you would expect of a head that’s spent the last 400 years buried in arid, tannin-heavy soil. The only real weak link is Carolyn Kearney, a real teenager who is every bit as bad an actress as all those pretentious little twits from your high school’s drama club. The fact that she happens also to be playing a simpering dolt doesn’t help any, either. Even here, there’s a small saving grace, though— after she gets possessed by Gideon Drew, her character gets shunted a bit to the side, and she mostly keeps her mouth shut from then on. In sum, it all comes across with a feel far more consistent with the strange, edgy movies the minor-league studios and independent producers were coming up with at the time, but without most of the raggedness that followed inevitably from the even more miniscule budgets the little guys always had to struggle with. I’m not sure The Thing that Couldn’t Die has made it to home video yet, but keep your eyes open. Somebody’s bound to get around to it sometime, and crazy shit like this pops up on late-night cable with surprising frequency.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact