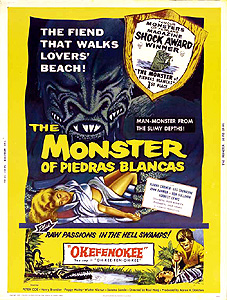

The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959) ***

The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959) ***

Of all the gill-man movies that were made after the trailblazing Creature from the Black Lagoon, the only one I’ve seen that I enjoyed more than The Monster of Piedras Blancas was the original version of Humanoids from the Deep. This movie, while not without its problems, is one of the finer achievements of late-50’s fly-by-night independent filmmaking. What we have here is essentially just a simple, old-fashioned monster flick, but its creators had an uncommonly focused idea of what they were doing, knew where to spend their pitifully small budget to greatest effect, and were willing and able to take advantage of their independence from meddling producers to throw in a couple of exploitation elements that they never could have gotten away with at one of the majors.

The setting is an isolated lighthouse perched above a treacherous stretch of southern California sea cliffs, just before sunset (I think— the day-for-night cinematography is a bit on the erratic side). Sturgis the lighthouse keeper (John Harmon, who would show up many years later in Microwave Massacre and The Unholy Rollers) notices a couple of men walking along the cliffs, carrying fishing tackle, and shoos them brusquely away. All Sturgis says is that the cliffs aren’t safe, an assessment which is patently correct, but all the same, one suspects that the lighthouse keeper may be talking about more than just the possibility of a fall down the slick, craggy cliff face. Maybe, for example, Sturgis has in mind the owner of those six-inch claws we briefly glimpse scraping something out of a battered metal bowl that somebody has chained to the rocks near the mouth of a cave just above the low-tide line...

The next day, Sturgis hops on his bicycle for a trip to the store. On the way up the beach, he encounters Constable George Matson (Forrest Lewis, from The Thing that Couldn’t Die and The Todd Killings), apparently the only cop in the one-Jeep town (no, really— the only motor vehicle we ever see is a war-surplus Willys-Overland) that is the nearest population center to Sturgis’s lighthouse. Matson and two other men are looking over the cleanly decapitated bodies of the Renaldi brothers, the two men Sturgis tried to warn away from the cliffs the night before. Sturgis tells the constable that he saw nothing, and then continues his ride into town. His destination is the tiny grocery store run by a non-specifically foreign man named Kolchek (Frank Avidson). Kolchek turns out to have been the one who found the Renaldis, and he proceeds to talk Sturgis’s ear off about his pet theory regarding their demise. Kolchek doesn’t buy the boating accident explanation that Matson is pushing pending a thorough examination of the bodies (a certain line of dialogue from Jaws springs to mind...); he thinks the Renaldi brothers ran afoul of the legendary Monster of Piedras Blancas, which has been rumored since Spanish colonial days to inhabit the caves that riddle the cliffs below Sturgis’s lighthouse. Sturgis, for his part, thinks Kolchek is a fool, but then again, he seems to get awfully worried when the shopkeeper tells him he sold the meat scraps he usually saves for Sturgis to a hog farmer from the other side of town. Hmmm... you know, those could have been meat scraps in that bowl in the first scene...

Meanwhile, Constable Matson is meeting with Dr. Jorgensen (Les Tremayne, from The Monolith Monsters and The Angry Red Planet) at the little restaurant that seems to be Matson’s main source of income. (One gets the impression that police work in these parts is usually a part-time job.) Jorgensen may not agree with Kolchek about any mythical monster, but he doesn’t think the Renaldis’ deaths were precisely accidental either; not only were their necks severed so cleanly that they might as well have been guillotined, their bodies were completely drained of blood— and yet there was scarcely a drop to be seen on the timbers of their mangled boat. Just then, Sturgis comes into the restaurant to talk to his daughter, Lucile (Jeanne Carmen, of The Devil’s Hand and Striporama), who works there behind the counter. Again, Sturgis brushes Matson off with claims not to have seen anything, but again, his conduct is otherwise suspicious. Specifically, it appears to bother him inordinately when Lucile tells him she’ll be working a double shift, and won’t be home until late at night.

He’s got good reason to worry. Lucile spends much of the day with her marine biology grad student boyfriend, Fred (Don Sullivan, from Teenage Zombies and The Giant Gila Monster), and it’s Fred who takes her home at the end of her shift in that one ancient Jeep. Fred goes to walk her home upon reaching the lighthouse, but Lucile assures him that she’ll be okay by herself, and the young man drives off. What happens next is absolutely amazing considering how old this movie is. Lucile waits until she’s sure Fred is well on his way, has a quick look around to make sure nobody else is on the beach, and goes skinny dipping! No fucking way! Sure, you don’t really get to see anything, but still... Anyway, while Lucile is frolicking immodestly in the surf, a familiar-looking clawed and scaly hand reaches over from just outside the frame, and grabs her discarded clothes. Sweet merciful crap! It’s the Panty-Sniffer of Piedras Blancas! But luck is with Lucile this night, for the monster soon puts her clothes back where it found them, and has backed off a bit by the time she finishes her swim. The girl is able to return home with no more indication of how close she came to a horrible fate than a vague sense that somebody has been watching her.

That peep show from Lucile must have had some effect on the monster, though, because it immediately heads into town, barges into the store where Kolchek is just finishing up for the night, and decapitates the rumor-mongering grocer. A child finds the body the next morning. More deaths follow in the ensuing days (including that of a prepubescent girl), along with an apparent attack on Sturgis himself, and the only clue to any of it is a big, weird scale that Fred found in the store beside Kolchek’s corpse. The scale isn’t from any fish or reptile that Fred or Dr. Jorgensen has ever seen, but it does bear a distinct resemblance to that of a supposedly extinct marine reptile called a Diplovertibron. Well, apparently we now know the scientific name for “gill-man;” just hours after they notice the resemblance between the scale from the store and the fossil scales of the Diplovertibron, Fred, Jorgensen, and Matson get their first look at the creature. (The real Diplovertibron was an extremely primitive amphibian, to which the monster in this film bears not the slightest resemblance.) They return to the store to have another look at the bodies of the victims, and the monster surprises them all by bursting forth from Kolchek’s meat locker carrying the severed head of one of Matson’s deputies! (The man who played that deputy, incidentally, is also inside the monster suit. His name is Peter Dunn, and he played monsters in Invaders from Mars, too.)

Well, now that our heroes have some idea what they’re up against, the stage is just about set for the final confrontation between man and sea monster. All we need now is some kind of explanation for what an ancient gill man is doing running around cutting off heads in southern California. That comes shortly after Fred tries to get Sturgis to open up about whatever it is that he’s obviously been hiding all movie long. Fred can’t pry the story out of him, but once Lucile tells her father that one of the monster’s victims was a little girl, he at last breaks down and explains the whole sorry business. Sturgis stumbled upon the creature’s lair by accident many years ago— just after Lucile’s mother died, in fact— and he took to feeding it (first on fish, then on those meat scraps he got from Kolchek) while Lucile was off at boarding school, eventually coming to think of it almost as a pet. The way Sturgis tells it, having the monster around helped him deal with the intense loneliness of life without his wife, a loneliness that was only compounded when he packed his daughter off for school in order to keep her from running into the potentially dangerous gill-man. The implication here is that, with the food supply it had come to take for granted cut off, the monster went looking for something else to eat, found the Renaldi brothers, and decided it liked the taste of human flesh and blood. So in a roundabout way, you could say Sturgis is partially to blame for the thing’s current rampage. And now that we know that, we also know where the anthropophagous gill-man is going to come looking for dinner next— after all, there wasn’t a movie monster yet born that didn’t eventually turn on its creator or benefactor, as the case may be. Sure enough, the monster comes calling at the lighthouse, where it somehow finds the time for one last attempt to run off with Lucile before becoming embroiled in the climactic battle against Sturgis, Fred, Matson, and a few extra characters of no real importance.

You see why I like this movie so much? It’s got a great monster suit, a skinny dipping scene, an impressive severed head, and a franker treatment of interspecies lust than any monster movie made since pre-Hays Code times. (We may not get to see what the monster does with Lucile’s clothes after it picks them up, for example, but because we’ve been told the creature mainly operates by smell, it isn’t too hard to guess.) There aren’t a lot of subplots, the filmmakers weren’t squeamish about doing awful things to juvenile characters, and the script doesn’t ask us to believe too many outrageously silly things. The poverty-row production values do sometimes get in the way— it’s awfully hard to get past the fact that everybody seems to take turns driving the same geriatric Jeep, for instance— and the monster’s eventual destruction is sort of anticlimactic. But I’m willing to overlook those shortcomings. The Monster of Piedras Blancas knows it’s just an unassuming little monster movie, and it fulfills its limited ambitions more than adequately.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact