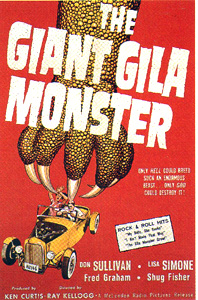

The Giant Gila Monster (1959) **Ĺ

The Giant Gila Monster (1959) **Ĺ

Iím beginning to think Ray Kellogg may have been the most underrated director of the 1950ís. Most folks rank him among the worst of the worst, and at first glance, itís easy enough to understand why. After all, itís hard to take a man seriously when his two biggest claims to fame are called The Giant Gila Monster and The Killer Shrews. But upon closer examination, it seems pretty clear to me that the bad reputations of both films stem primarily from the undeniable and distractingly conspicuous lousiness of their special effects. The monsters in The Killer Shrews are dogs wearing carpets, and yeahó thatís pretty sad. Youíll get no argument from me on that score, nor will you hear me say much in defense of the HO-scale miniature work in The Giant Gila Monster. But hiding behind those hysterically sorry special effects are a pair of surprisingly solid monster flicks. That isnít quite so much the case with this movie as it is with its companion piece (The Giant Gila Monster is further hampered by some almost painful efforts to work as a mid-50ís-style rock and roll movie), but itís still a great deal better than I remember it being.

The Giant Gila Monster begins with a prologue similar to those of Bert I. Gordonís more accomplished, late-50ís movies; as weíll be seeing later, this is only appropriate. A car speeds down a winding country road in the middle of the night, until it is suddenly knocked clear off the pavement by something huge. The huge something looms over the passengers as they try to free themselves from the wrecked vehicle, and thatís the last anybody will ever see of them.

We may safely assume that the Mr. Wheeler (Bob Thompson) who comes around bothering the local sheriff (Fred Graham, from Panther Girl of the Congo and The Crimson Ghost) about his missing son the next day is talking about one of the people who were riding in that car. Wheeler is operating on the assumption that the boy ran off to seek trouble with his idol, hotrodder Chase Winstead (Don Sullivan, also seen in Teenage Zombies and The Monster of Piedras Blancas), but the sheriff has a different idea. For one thing, he knows that Winstead, despite his reputation, is easily the smartest, steadiest, most responsible adolescent in town. For another, he knows that the Wheeler boyís girlfriend has also gone missingó perhaps the two of them have simply eloped? It would hardly be surprising, given both Mr. Wheelerís dictatorial parenting style and his vocal disapproval of the relationship between his well-heeled son and the daughter of a pair of impoverished white-trash dirt-farmers. Wheeler bridles at the suggestion, but eventually shuts up and leaves the sheriff alone to do his job.

Sheriff Jeff recognizes that Wheeler has one small particle of a point, howeveró that if anybody knows where the missing kids have gone, itís Chase Winsteadó and with that in mind, he goes to see Chase at Comptonís garage, where he works as a mechanic and tow truck driver. Compton himself (Cecil Hunt) is out on an errand, buying about a gallon of nitroglycerine for no apparent reason (Foreshadowing Flare! *Foomp!*), so Winstead has plenty of time to talk to the sheriff about his two younger friends. Chase honestly has no idea what might have become of either Wheeler or his girlfriend. They werenít ďin any troubleĒ (that is to say, they hadnít managed to get the girl knocked up) to the best of his knowledge, and neither one said anything to him about planning on sneaking away, for any reason.

Thatís when the wrecked cars start showing up along the road that runs parallel to the old dry riverbed outside of town. The first turns out to have been stolen. Whoever pinched it must have figured the safest escape route led through the country, but then lost control of the vehicle while rounding a bend. Something about the scene of the wreck doesnít compute, though. For one thing, the dents on the side of the car arenít quite right; they look like they were caused by a single, huge, irregular object striking the side of the car once, rather than by a roll down the embankment, with its attendant sustained battering from stones and stumps and assorted other hazards. Not only that, the skidmarks on the pavement run perfectly straight, and perfectly perpendicular to the axis of the road. The sheriff has never once seen a skidmark like them. The second distressed vehicle isnít a wreck, per se, but merely a close call. Local radio personality Horatio ďSteamrollerĒ Smith (Beyond the Time Barrierís Ken Knox), driving drunk, runs off the road while attempting to dodge something rushing across it. When Chase picks him up for the tow, Steamroller tells him that whatever he was dodging was much too big for him to get a fix on its shape, but that it was a long, black thing with lots of little pink stripes. Chase understandably figures thatís just the alcohol talking, and thinks nothing more of it. Finally, the Wheeler boyís car turns up at the bottom of the riverbed. Itís smashed up in exactly the same strange way as the first wreck was, and thereís blood on the seats. Chase, his exchange-student girlfriend, Lisa (Missile to the Moonís Lisa Simone), and two of Winsteadís other friends search the densely wooded gully for a while, but they never do find any bodies. Luckily for them, they also donít find the gargantuan gila monster thatís been watching them through the trees the entire time.

The first person to do that is Harris, the town drunk (Shug Fisher). He happens to be on the scene when the monster lizard derails a train, and he tells the sheriff the whole strange story later that night. Now you might expect Jeff to laugh in Harrisís face and lock him in the drunk tank, but while he does indeed lock the man up, the sheriff doesnít do any laughing. Not long ago, he read a story in the newspaper about a baby in Russia who grew up freakishly big, freakishly fast because of a combination of toxic chemicals in his familyís well-water, and if it could happen to a human, then why not to a gila monster too? Meanwhile, confirmation is on its way sooner than anyone wants, because Chase and his friends are throwing a big party this Saturday night at a barn not far from the monsterís lair. Between the noise and the tempting smell of all those delicious teenagers, thereís just no way the immense lizard isnít going to gate-crash. I guess we know what that nitroglycerine was for now, donít we?

With The Giant Gila Monster, we sort of have two movies happening at once, and one of them is much better than the other. The famous limitations of the special effects aside, the filmís monster-movie aspects are handled quite well. Kellogg is to be commended for not falling back on the A-bomb clichť to provide his monsterís origin, and a few of the stalking scenes are unexpectedly suspensefuló the death of the hitchhiker especially so. The director also does a pretty good job convincing us that the lizard is bigger than usual, although itís impossible to tell until the climactic attack on the lamentably cheesy barn set just how much bigger itís supposed to be. In his role as screenwriter, Kellogg keeps his contrivances to a minimum (thereís that business with the nitroglycerine, of course, but thatís pretty much it), and he makes at least some effort to treat most of his characters more honestly and believably than was typical of the genre at the time.

Unfortunately, when The Giant Gila Monster steps beyond the boundaries of the monster mash, things start to go wrong in a big way. Kelloggís bids for direct teen appeal are outright embarrassing. Itís enough that Chase Winstead is portrayed as a saintly but misunderstood pseudo-hoodlumó making him a secretly aspiring rock and roll star too is really pushing it. Then Kellogg compounds the error by grossly mishandling that aspect of the plot. We only get to hear half of Chaseís swinging dance number, but his obnoxious homebrew hymn (ďThe Lord said, ĎLaugh, children, laughíÖĒ)ó sung to the accompaniment of a childís toy banjo, no less!ó gets played in its entirety twice! And in an especially perverse display of youth-culture cluelessness, itís the latter song that proves the bigger hit among Winsteadís teenage followers. Iím sorry Ray, but the current popularity of Creed and MXPX aside, thatís not how it works! In fact, the one positive thing I can think of to say about The Giant Gila Monster in its capacity as a teen movie is that Kellogg certainly seems to have a handle on the ways of hotrodders. The covetous manner in which Chase and his friends eye Old Man Harrisís 1932 Model-A Ford coupe is absolutely spot-on. But for the most part, all that clumsy teen stuff is just a misguided sideline. The Giant Gila Monster spends most of its time being exactly what it sounds like, and at that it does a pretty respectable job.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact