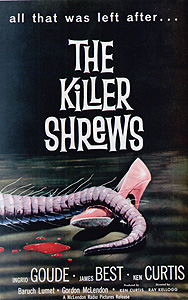

The Killer Shrews/Attack of the Killer Shrews (1959) ***½

The Killer Shrews/Attack of the Killer Shrews (1959) ***½

It’s hard to believe that Ray Kellogg, the man who gave us The Giant Gila Monster, is also responsible for one of the last great monster movies of the 1950’s, and it’s even harder to believe that such praise could be deserved by a movie about giant, man-eating shrews. But as daffy as it may sound, The Killer Shrews/Attack of the Killer Shrews has some real kick to it, in a way that few other low-budget 50’s monster flicks do.

It begins with two men, Thorne Sherman (James Best, from Riders to the Stars and Shock Corridor) and Rook Griswold (Judge Henry Dupree), sailing their small boat out to a remote island, into the teeth of a developing hurricane. Their mission is to bring a load of supplies to the home and laboratory of a Swedish scientist named Dr. Milo Craigis (Baruch Lumet). When they make landfall, Craigis is there to greet them, along with his daughter, Ann (Ingrid Goude), and her fiance, Jerry Farrell (Ken Curtis, from “Gunsmoke”). Craigis wants Sherman to take Ann back to the mainland as soon as he unloads the provisions from his boat, but Sherman is forced to disappoint him; apparently, Craigis has no radio, and was thus unaware of the storm heading towards his island. With nothing to do but wait until the hurricane blows over, Sherman accompanies Craigis, Ann, and Jerry back to the house, leaving Rook to look after the boat.

The reason Craigis and Jerry give for wanting Ann off the island is that there are dangerous animals roaming the woods that cover most of it. This is bad news, but it isn’t half the real story, which only gradually emerges over the course of the next half-hour. The first hints come when Craigis’s colleague, Dr. Radford Baines (Gordon McLendon, executive producer of both this movie and The Giant Gila Monster), brings in one of the experimental animals from the lab to show to the other scientist. The animal is a shrew. Now these little critters don’t look like much, considering that they are the world’s smallest mammals, but don’t be fooled by appearances— if you’re a bug or a field mouse, there’s nothing in the world scarier than a shrew. As Craigis explains for the benefit of both Sherman and the audience, shrews, though they prefer insects, will eat just about anything they can fit down their throats, and their extraordinarily high metabolism demands that they eat some three times their body weight daily in order to survive. Craigis is working with shrews because their very short lifespans and commensurately brief breeding cycle make them well suited for genetic research. Craigis hopes to find a way to genetically engineer small body size without the usual concomitant increase in metabolic rate— his ultimate aim is an unusual reversal of the typical 50’s sci-fi approach to the problem of world hunger. Rather than develop strains of super-sized food plants and livestock, Craigis wants to find a way to breed human beings down to half their current size, while keeping the comparatively slow metabolism we have now. Instead of increasing the food supply, he’s looking to decrease the demand. This, naturally, means doing all sorts of funny things to his shrews’ genomes, and we all know what happens in the movies when scientists do that!

And indeed it is only a few hours later, after Sherman has finally gotten fed up with all of the mystery, that Ann unloads the whole story: how her father miscalculated with one of the experimental groups and created the exact opposite of what he was aiming for (large size and fast metabolism), how her irresponsible drunk of a fiance allowed the husky-sized shrews to escape, how the Craigis team has been holed up in the house ever since, waiting in fear of the day when the island’s food supply inevitably runs out, and the shrews start looking to their human neighbors to slake their ravenous appetites. Her divulging all this provokes a major flare-up of the hostility we’ve been glimpsing just below the surface every time Jerry interacts with her or Sherman, which is not altogether surprising, given that the whole killer-shrews-at-large-in-the-woods problem is mostly Jerry’s fault.

Meanwhile, the shrews waylay Rook while he ties a long rope from the boat around a tree a dozen or so yards in from the shore, in order to help steady the vessel against the mounting winds of the oncoming hurricane. The attack on Rook is one of the earliest instances I know of in which the oft-observed principle that the one black character will be the first to go comes into play. By the time the shrews finish with him, all that’s left are his shoes, a few scraps of clothing, and his empty revolver.

The nasty beasts start showing up at the house a short while later. Before long, one of them discovers that the driving rain from the storm has turned the adobe walls of the house back into mud in those places where the outer plaster covering has weathered away, and burrows its way into the cellar. The ensuing confrontation between the monster shrew and its human prey reveals that our heroes are in even bigger trouble than they realized. The shrew has a chance to maul the leg of Mario (Alfredo DeSoto), Craigis’s domestic, before it is shot down by Sherman, and the man dies quite swiftly even though his wounds, though serious, should not have been life-threatening. When Dr. Baines analyzes the shrew’s saliva, he discovers that the mutant creatures have somehow become lethally venomous as well as extra-large; evidently, even the slightest scratch from the monsters’ fangs is fatal.

From here on out, it gets worse and worse, in a way that bears striking resemblance to the later Night of the Living Dead. The shrews waste little time in exploiting their discovery that the walls of the house are no match for their burrowing claws, the trapped humans find their menu of options for escape dwindling, and tensions between Jerry and Thorne threaten to split the group apart and siphon off energy and attention desperately needed for coming to grips with the monsters. The only ray of hope lies in two details of shrew biology: they can’t swim, and they are perfectly happy to resort to cannibalism if no other food is available.

Most observers take one look at The Killer Shrews’ titular monsters and dismiss the film out of hand. Admittedly, the monsters— a combination of none-too-convincing puppets and dogs wearing equally shoddy costumes— are pretty weak, especially by modern standards. Nevertheless, to write The Killer Shrews off this way is a big mistake. Hiding beneath the bargain-basement special effects is an extremely economical, shockingly suspenseful movie, with unexpectedly complex characters, a fast-moving, engaging story, and quite a bit of imagination. Neither Craigis nor Baines is the stereotypical mad movie scientist, nor is Sherman the stereotypical two-fisted 50’s hero, although both characterizations might seem to fit at first glance. The scientists, in marked contrast to the norm, realize the magnitude of their screw-up, but they have taken what they regard as sensible precautions for containing its effects, and they have continued on with their work having learned from the experience. (Compare this to any of the hundreds of films in which their counterparts either go to their graves heedless of the damage their experiments have caused, or give up their research altogether when something serious goes dangerously wrong.) And Sherman, for his part, is far less than the perfect good guy. Note the sequence in which he and Jerry go looking for Rook after the shrews’ first night attack. When the bloodthirsty beasts chase them back to the Craigis house, Jerry shuts the gate to the palisade-like backyard fence before Thorne can get inside, forcing him to climb over instead with the shrews snapping at his heels. Once inside, he attacks Jerry, beating him senseless, and in the heat of the moment, he nearly throws his defeated opponent to the shrews before he realizes quite what he’s doing. The psychological fallout from Thorne’s brush with manslaughter is portrayed with more realism than one typically finds in a reputable drama, let alone a two-bit monster flick. After two decades of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Stephen Segal movies, it’s really striking to see a film contend that an emergency need not turn a man into a savage beast, and that the usual norms of morality are not suspended in a crisis, even one as dire as an attack by hundreds of giant, man-eating shrews.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact