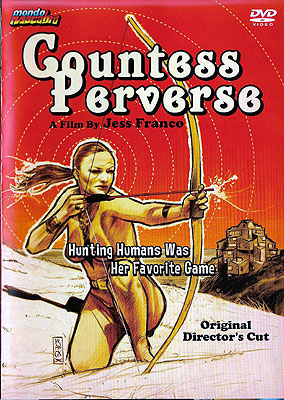

The Perverse Countess / Countess Perverse / La Comtesse Perverse (1973) ***

The Perverse Countess / Countess Perverse / La Comtesse Perverse (1973) ***

The Perverse Countess has been a grail movie for me since about 1999, when I read a review of it on an early incarnation of Teleport City. Don’t bother looking for it on the current site— that review dropped out of sight several revamps ago. But the moment I learned that Jesus Franco had made a pornoed-up lesbian interpretation of The Most Dangerous Game (actually, he made at least two to four, depending on how you count alternate versions of this one, plus 1997’s Tender Flesh), I knew that was something I simply had to see. Now that I have, I’m pleased to report that like all the best Franco, The Perverse Countess is both everything I wanted from a sex-horror oddity, yet also nothing I expected, even with that old review to guide me. And as an unlooked-for bonus, it manages to retain its grail status for me thanks to the significantly variant forms in which it was released after the initial edit failed to drum up any interest at Cannes in 1973.

We begin with a young couple— Bob (Robert Woods, from The Lustful Amazons and The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff) and Moira (Tania Busselier, of Greta the Mad Butcher and How to Seduce a Virgin)— hanging out on the veranda of their villa overlooking the beach. Suddenly, Bob spots something on the strand below, a nude woman (Kali Hansa, from Sinner: The Secret Diary of a Nymphomaniac and The Erotic Exploits of Maciste in Atlantis) sprawled out in the surf like a castaway. He and Moira retrieve her from the waves and carry her up to their living room, where she half-deliriously relates an incredible tale.

The woman from the beach is apparently a local. Growing up, her twin sister was always afraid of a certain island off the coast, yet it was on that self-same island that the latter girl disappeared without trace or explanation. A few days ago, our narrator hired a boat pilot to take her to the mysterious isle as well, in the hope of finding some sign of her twin. What she discovered was a strange, solitary house perched right on the edge of the sea cliffs. There, she met Rador (Howard Vernon, of Deadly Sanctuary and Faceless) and Ivanna (Alice Arno, from Tender and Perverse Emmanuelle and My Body Burns), the Count and Countess Zaroff. They welcomed her at first, treating her to a sumptuous meal of roasted game from their own hunting preserve and inviting her to stay the night in the chateau, but their demeanor changed drastically once they had their guest ensconced in one of their many spare suites. First they let themselves into her quarters while she was sleeping, and took turns raping her until she liked it. (If you ever wanted to know what the back of Howard Vernon’s scrotum looked like, here’s your chance to find out…) Then the next morning, the Zaroffs turned her loose in the hunting preserve, naked and unarmed, so that the countess could practice her favorite sport. Somehow the fox escaped the hounds on this occasion, reaching the shore of the island unhurt and unobserved, from which she desperately swam until the current carried her back to the mainland.

Bob and Moira’s reaction is not at all what their guest was expecting. Once they sedate her to calm her frazzled nerves, the couple take her out to their boat, and return her to the Zaroffs! It turns out they’ve been procuring for the decadent aristocrats for some time. Hell, they probably sold the Zaroffs Beach Girl’s missing twin. Evidently Bob and Moira are in some kind of trouble with the law, and stocking Ivanna’s hunting ground is the only way they’ve been able to think of to raise enough money to effect their permanent escape. Bob, interestingly, is more troubled by their approach to fundraising than Moira. Nevertheless, he doesn’t refuse a day or two later, when the count calls to order yet another girl.

Fortuitously, the couple have a friend by the name of Sylvia (Lina Romay, from Barbed Wire Dolls and Macumba Sexual) who apparently isn’t from around here. She’s staying at the Hotel Salinas, in a cramped room with no direct beach access, and thus isn’t getting as much out of her visit to the coast as she would have liked. Seizing the opportunity, Bob and Moira invite Sylvia to move in with them for the remainder of her stay. Not only does that make her handy for turning over to the Zarofffs, but it also lets them have some fun in the meantime. I mean, what would you do if a nineteen-year-old Lina Romay were staying at your house? The time soon comes, though, when the couple must fulfill their obligations to the countess, by which point the situation has become rather complicated. Moira maintains her self-interested detachment, but Bob has grown infatuated with Sylvia. Indeed he finds that he’s starting to prefer her to Moira. Over the coming days, as the Zaroffs host Sylvia in preparation for Ivanna’s next big game hunt and cannibal barbecue, Bob increasingly feels the goading of what remains of his conscience. And as the hunt itself begins, the guy who got Sylvia into her predicament in the first place resolves to do whatever it takes to get her out of it.

The Perverse Countess is another one that Franco had a hard time selling once it was finished, and as usual, it isn’t hard to fathom why. It defies marketing categories, being far too much a softcore porno for the regular horror market, and far too sadistic for any but the kinkiest porn customers. The former audience is sure to revolt at the short shrift given to the human-hunting, while the latter wants to fantasize about banging Kali Hansa and Lina Romay, not eating them! Both sets of reshoots and re-edits conducted over the following two years were designed to tone down the ghoulish implications of the original Perverse Countess, and to turn it into more of a conventional sex movie. However, we’ll have to save detailed discussion of that for the day when I find myself a copy of either The Munchers (the revised French cut from 1974) or Sexy Nature (the 1975 Italian version).

In its intended form, The Perverse Countess looks at first like a fairly shitty movie, but it reveals hidden depths upon close examination. It’s easiest to see what I mean in the cinematography by frequent Franco collaborator Gerard Brisseau. As you would expect from an early-70’s Franco movie, The Perverse Countess is sorely afflicted with spazz-pans and zoom seizures, but those familiar defects are subtly counterbalanced and maybe even cancelled out by impressively inventive frame composition and unconventional use of deep-focus lenses, giving the whole film a faintly distorted, dreamlike quality, and emphasizing its status as a sort of dark and deviant fairy tale.

Meanwhile, on the soundtrack, it’s veritable war between relatively normal horror and sex-movie music (like the skittering violins that accompany the first victim on her journey to Chateau Zaroff, or the flute-driven soft jazz pieces that play over most of the sex scenes) and two sharply differentiated genera of cues so strange you’d swear at first that there was no natural home for them in any movie’s score. The more purely regretable of the latter are the crudely thudding organ cues that represent, more or less, the wave of uncanny terror that overcomes everybody the first time they lay eyes on the Zaroffs’ castle. It sounds like somebody’s handed over the keyboard to a halfwit orangutan, and it prefigures the music in most of Franco’s movies from the 1980’s by wrecking the mood of everything it touches. But once night falls on Sylvia’s stay at the chateau, the soundtrack is dominated instead by a quartet of wild acid-rock compositions that gradually come to seem the perfect accompaniment to the action onscreen, melding with it far better than any more “appropriate” music could. The most normatively psychedelic of the lot is the theme for Ivanna and Sylvia’s frenzied fucking, perved on through a translucent drapery by the count. Countess Zaroff’s hunting theme combines its wailing fuzztone guitar with pseudo-Afro exotica, all syncopated drums and monkey calls. The really arresting rock cues, however, are the two that I think of as “Sylvia on the Run” (which pulls double duty as The Perverse Countess’s opening credits music) and “Bob to the Rescue.” The former is practically a primitive form of heavy metal, while the latter shockingly anticipates the New York junkie-rock school of punk. Both are sinister, adrenalin-charged pieces well mated to scenes of tension and potential violence. So as with the camerawork, what seems at first to be a half-assed-mess turns out to have a lot of not-immediately-obvious care and attention put into it— along with a considerable amount of very real half-assedness.

Then there are a couple points on which Franco has simply nailed it here. For starters, no one could have chosen a better location to represent the Chateau Zaroff. It’s the same place that served as Soledad Miranda’s house in She Killed in Ecstasy, a luxury apartment block in Alicante called Xanadu. (I swear, that Franco-Welles connection manifests itself in the strangest of ways sometimes…) An ultra-modernist, geometric pagoda, Xanadu juts from the arid landscape like a cubist’s hallucination, as unsettling as it is beautiful. Then, for one of the key chateau interiors, the spiraling staircase of blood-red stone that the Zaroffs and their guests must descend on their way to the castle’s main living spaces, Franco turned to the Murala Roja, the even weirder place next door. (Note, however, that all the exterior shots of Xanadu are composed so as to present no sign of its neighbor’s existence. The Chateau Zaroff always looks like it’s the only human dwelling for miles around.) Similarly, consider the towering islets of apparently solid rock that guard the seaward approaches to the Zaroffs’ lair like miniature Gibraltars. Franco lingers on those in a way that seems unjustified from a narrative point of view, but which pays huge dividends in creating and sustaining the aura of dread that surrounds the villains.

All of the above hints, I think, at what really makes The Perverse Countess essential Franco. More than any other movie I’ve seen, this one illustrates the importance of intuition to Franco’s direction. Throughout the film, Franco seems to be doing things not because they make any rational sense (in fact, very little of The Perverse Countess makes any rational sense), but because they produce a particular emotional impact. Let’s look again at the stairs from the Murala Roja. Remember that I said the characters descend them upon entering the chateau. It’s spatially impossible, but it feels right anyway because everyone knows that the route to Hell leads down. Time gets even further out of joint than space in The Perverse Countess. Indeed, especially once Sylvia arrives on the island, it’s as though the action is arranged less chronologically than thematically. At one point, Sylvia walks in on the Zaroffs cutting up a body that they already ate (and fed to her) at supper that evening. The scene in which Bob reaches his snapping point is shown after events at the chateau which must have preceded it by hours. It’s all very disorienting, in a way that seems neither entirely deliberate nor entirely accidental. The most likely explanation, or so it seems to me, is that Franco during this period worked mainly by feeling his way along, knowing where he wanted to go, but relying on the inspiration of the moment to get him there. It seems odd that such a loose and unstructured approach could coincide with the most prolific period of someone’s career, but the very nature of Franco’s productivity in 1973 supports the argument. The dozen-plus movies he made that year circle obsessively around a set of recurring elements, and several of them would eventually be released in two or three parallel versions each. On top of that, there were a further three films that Franco abandoned unfinished in ‘73, having decided that he didn’t like the way they were turning out. That’s not the behavior of a detail-oriented planner. Especially once you factor in the two-week shooting schedules that most of these pictures had, it starts to look almost like the cinematic equivalent of automatic writing. At the very least, 1973 saw Franco perfecting, if we can call it that, the cinema-as-jazz methodology which first becomes apparent in his work from the late 1960’s. Sometimes that methodology was successful, sometimes it wasn’t, and sometimes its failures produced their own strange forms of derivative success. In The Perverse Countess, we get all three outcomes at once.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact