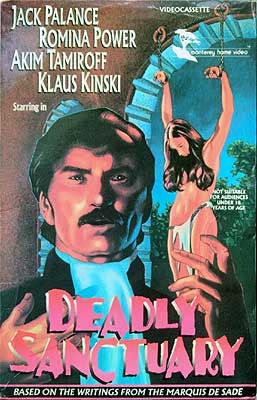

Deadly Sanctuary / Marquis de Sade: Justine / Justine and Juliet / Justine, ovvero Le Disavventure della Virtu (1968/1969) -***

Deadly Sanctuary / Marquis de Sade: Justine / Justine and Juliet / Justine, ovvero Le Disavventure della Virtu (1968/1969) -***

I didn’t realize it at the time, and I wouldn’t have understood the significance if I had, but Deadly Sanctuary was my introduction to Jesus Franco. It was also my introduction to Jack Palance’s European-made rent-payers, the significance of which was immediately apparent. As I gazed deeper into both abysses over the ensuing years, I came to realize that this movie was far less typical of the former than the latter. If you want to see Palance get up to bad-movie shenanigans abroad, Deadly Sanctuary will give you a fair idea what to expect (although his performances weren’t usually this extreme, nor was he usually this visibly inebriated). But it’s a peculiar film for Franco on many levels, even granting that his late-60’s alliance with British producer Harry Alan Towers was something of a career interlude anyway. For one thing, this was the most expensive movie Franco would ever make, and the relatively lavish budget bought things that none of the director’s other pictures have. Most conspicuously, there’s the unprecedented number of name performers, drawn from America, Britain, and a broad swath of Continental Europe. More subtly— subtly enough, in fact, that only experienced Franco-philes are likely to notice how unusual this is— there’s the adequately convincing period setting and the impressively large flock of extras, either one of which would have consumed the entire capital base of the typical Franco film. Towers was important for more than his money, too, because his involvement (along with that of some Italian partners) made Deadly Sanctuary an international production, subject to different and laxer censorship standards than a purely Spanish effort. That is, just by being a foreigner, Towers gave Franco ammunition for a new skirmish in his ongoing battle against the Fascist morality police. A risky skirmish it would be, too, because with Deadly Sanctuary, Franco was doing something that few filmmakers before him had ever attempted: he was directly adapting a novel by the Marquis de Sade.

That doesn’t sound unthinkably transgressive in 2015, I realize, but I’m not at all certain that Franco was joking many years later, when he told an interviewer that this movie would have gotten him jailed had he made it without the cover of foreign backers. Europe was still in something of a tizzy over de Sade even after a century and a half. As recently as 1955, for example, the French government had seriously considered rounding up all of his surviving manuscripts and burning them. And both previous treatments of de Sade on film were disreputable indeed in the eyes of the Spanish authorities. Luis Buñuel had referenced 120 Days of Sodom in The Golden Age (although it would be stretching the point to call that an adaptation), and Roger Vadim’s Vice and Virtue had used Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue as a prism through which to examine the moral and psychosexual pathology of Nazi Germany— so Franco’s predecessors were, so far as the Fascist censors were concerned, an anarchist and a pornographer. Just the company one wants to be seen in, right? Nor would the specific novel from which Franco was working have helped his case any. Deadly Sanctuary too was a version of Justine, probably as close as de Sade ever came to a complete encapsulation of his philosophy of libertine radical individualism. At the very least, that book meant enough to him that he rewrote and expanded it several times over the course of his career. In form, Justine belongs to a curious 18th-century mini-genre dedicated to taking down Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, but while most of the anti-Pamelas were written more or less in jest, de Sade was seemingly dead earnest in arguing that being good was a sucker’s game, and that evil was much more fun besides. That more than anything earned de Sade his reputation as the world’s most dangerous writer— dangerous enough that Napoleon himself ordered the author’s imprisonment after encountering one of the later Justine variations. And now the man whom no less an authority than the Vatican singled out (along with the aforementioned Buñuel) as the world’s most dangerous filmmaker was bringing Justine to the screen without the reassuring distancing device of a Nazi German setting. No wonder Franco decided soon thereafter that Spain was getting too hot for him!

That isn’t to say, however, that Deadly Sanctuary is without a distancing device of its own. The Marquis de Sade did most of his writing in prison, and the movie begins with the author (Klaus Kinski, from Psycho-Circus and The Black Abbot) about to begin one of his many terms of incarceration. Periodically throughout the film, Franco will return to the marquis’s cell to eavesdrop on him as he writes the story we’ve been watching. More often than not, these intermissions will find de Sade tormented by phantasms of women in the throes of sexual mistreatment— phantasms which we’re invited to believe inspire him as he turns the tale in ever more depraved directions. I call this a distancing device because it functions to keep us always aware of de Sade’s authorial presence. It allows Franco to say in effect, “Don’t look at me, man— I only work here.”

The tale itself concerns two sisters who could not be more unalike, the gentle, trusting Justine (Murder by Music’s Romina Power— Tyrone’s daughter) and the crafty, calculating Juliet (Maria Rohm, of Venus in Furs and Count Dracula). The girls have lived and studied in a convent outside Paris ever since the death of their mother when they were but children, and we meet them just as they’re getting more bad news. Their father has died, too, after a run of foul luck destroyed his small but prosperous business empire, and although each sister is due a comfortable inheritance of 100 crowns, that won’t stretch far enough to cover their room, board, and tutors’ fees until they reach age of majority. So unless Justine and Juliet would like to take monastic vows, they’re going to have to leave the convent as soon as their money comes in.

Juliet, worldly as she is despite her nunnery upbringing, naturally takes the lead in figuring out how the sisters will manage on their own. She’s heard of a house in the city where the owner, one Madame de Buisson (Carmen de Lirio, from The Evil Forest and Goliath and the Giants), makes a habit of taking in young girls with nowhere else to go. Both sisters are dismayed when the establishment in question turns out to be a whorehouse, but Juliet figures there are worse ways to make a living, especially since turning tricks for Madame de Buisson means living in a lushly appointed chateau amid the lively company of a dozen other girls. Justine, on the other hand, leaves in a huff. Nobody’s making a prostitute of her, least of all her own sister!

The contrasting fates of the two siblings from that point forward are the means whereby de Sade develops his thesis of doing unto others before they get a chance to do unto you. Falling under the tutelage of a veteran whore named Claudine (Eye in the Labyrinth’s Rosemary Dexter), Juliet does very well for herself at the brothel, but soon comes to resent Madame de Buisson claiming the bulk of her stable’s earnings for herself. She conspires with Claudine to murder the madam, rigging the scene to suggest that she hanged herself after stabbing her lover to death in the chateau’s master bedroom. Then Juliet and Claudine abscond with all the valuables they can carry (rather blowing their cover story, if you ask me), and set off on a nomadic life of whoredom, robbery, and homicide. Eventually, though, Juliet falls in love with a count (Gerard Tichy, of A Hatchet for the Honeymoon and The Blanchville Monster) from whom she could never practicably steal as much as she stands to gain by becoming his permanent mistress. Her partnership with Claudine isn’t the sort one just walks away from, however (each girl has enough dirt on the other to get her hanged twenty times over), so Juliet drowns her in a river while they’re bathing together, and then rendezvous with her sugar daddy to begin her third new life in earnest. We’re given every reason to imagine it as one of the “happily ever after” persuasion, too.

Justine, meanwhile, makes every effort to do the right, proper, and respectable thing at all times, and gets so regularly shat on by both her fellow humans and the universe at large that one is tempted to look for the American Standard logo stenciled somewhere on the back of her neck. First she gets conned out of her entire inheritance by a greedy friar. Then an even greedier innkeeper (Akim Tamiroff, of The Vulture and The Black Sleep) takes her in as a housemaid, but sells all her clothing, tries to whore her out to the upstairs tenant (Gustavo Re, from The Castle of Fu Manchu and The Colossus of Rhodes) while suborning her into stealing from the renter on his behalf, and finally throws her to the cops in his own stead when the victim notices some of his jewelry missing. (Assholes attempting to get Justine to commit crimes for them, then doing it themselves when she refuses, and framing her afterwards, are going to become a recurring pattern in the girl’s life.)

Justine gets what looks like a lucky break in prison, when the hardest hardcase behind the walls becomes her protector. Madame Dubois (99 Women’s Mercedes McCambridge, whom my readers are most likely to remember for dubbing Linda Blair’s post-possession voice in The Exorcist) has been earning a dishonest living long enough to spot a lie at horizon range, so she recognizes at once that the new girl truly is innocent of the crime for which she’s been condemned. Indeed, Madame Dubois goes so far as to bring Justine along when her gang busts her out on what was to have been the day of her hanging. Justine’s escape carries with it a hefty dose of survivor’s guilt, however, because the Dubois gang springs the women from their confinement by burning down the prison! Furthermore, the men expect to be paid in pussy for including Justine in the breakout. Luckily for her, they quickly fall to squabbling over who gets to rape her first, and she is able to slink away during the ensuing brawl.

Justine’s next stop is the home of an artist named Raymond (Harald Leipnitz, from Creature with the Blue Hand and The Sinister Monk), the one person she meets in her travels who isn’t a conscienceless predator. He asks no embarrassing questions when the fugitive girl appears on his doorstep, obviously in need of aid. He takes no advantage of her while she hides out at his house, makes no complaint about how much she eats or about having to part with a set of his own garments to keep her decently clothed, and asks for no compensation beyond Justine’s permission to paint her picture. The pair soon fall in love, and Justine gives Raymond willingly what so many before him have tried to take by force. She’s still wanted by the law, though, and it isn’t long before a squad of gendarmes come by the painter’s place looking for her.

This time, Justine’s flight leads her into the clutches of the homosexual Chevalier de Bressac (Horst Frank, from The Dead Are Alive and The Head), whom she stumbles upon while he’s tarrying in the woods with his lover, Jasmin (Angel Petit— remember, Angel’s a boy’s name if you’re Spanish). At first, the two men try to teach Justine a rapey lesson about spying on her betters, but they’re disappointed to find the wrong set of equipment once they get her out of Raymond’s clothes. Still, de Bressac is clever enough to recognize a fugitive when he sees one, and unlike Raymond, he’s quick to exploit any advantage. For the next three months, Justine serves de Bressac’s wife, the marquise (Sylvia Koscina, of Lisa and the Devil and The Crimes of the Black Cat), as her chambermaid, building up her trust for— that’s right— a dastardly crime on the chevalier’s behalf. You see, all the family property except for one 50,000-crown-per-year estate belongs to the marquise. If she were to die, her husband would get it all, leaving him so well set up that he wouldn’t even need a beard anymore. But instead of poisoning the marquise as instructed, Justine reveals the chevalier’s plan— which goes just as well for her as her principled refusal to rob the innkeeper’s tenant before. They apparently do things differently out here in the sticks, though, because instead of handing Justine over to the police, de Bressac turns her loose after branding her in the cleavage with a great, big murderer’s “M.” I bet Justine makes lots of pals now…

Virtue’s greatest misfortune is still to come, however. Having been tipped off that a certain abbey is home to four holy men who have shut themselves away in contemplative seclusion, Justine heads there in the hope of resuming the kind of life she led at the convent. Her initial interview with Clement, the number-two hermit (Howard Vernon, from Revenge in the House of Usher and Lorna the Exorcist) goes well enough, but things start looking decidedly fishy when she meets Brother Antonin the abbot (Palance, of Hawk the Slayer and the Dan Curtis Dracula), and finds him attended by a harem of bare-breasted girls. The hermits are basically Clive Barker’s Cenobites without all the body piercings, and what they contemplate up in their abbey is the outermost frontier of sadistic pleasure. By the time Justine makes her escape with the help of a convenient lightning strike and a fellow inmate called Florette (Rosalba Neri, from The Girl in Room 2A and Lady Frankenstein), she’s beginning to think maybe Brother Antonin and her creep sister are on to something. And even then Justine’s troubles are not at an end, for although she is fortuitously found lying in a muddy road by none other than her lost love, Raymond, the village where he takes her in search of a doctor just happens to be playing host to a traveling carnival run by the Dubois gang, the men of which are still sore about Justine skipping out on her rape appointment way back when.

One thing you should already be able to tell about Deadly Sanctuary is that it’s rather too episodic and repetitive for its own good. I’m sure at least part of that stems from the source material, but that doesn’t make it any less frustrating when, for example, the Chateau Bressac segment exactly recapitulates the inn segment, only with more gilt, red velvet, and powdered wigs. At the same time, we don’t see quite enough of Juliet, undercutting the contrast between the sisters’ experiences that establishes the movie’s thematic through-line. And I’m torn on the subject of the periodic visits to de Sade’s prison cell. On the one hand, it’s always a pleasure to see Klaus Kinski overact, and this is a magnificently unhinged performance even despite the complete lack of dialogue. But if the problem is that Deadly Sanctuary is too episodic, then having yet a third set of episodes breaking up its structure is obviously undesirable. And if repetition is the problem, then it’s doubly undesirable for that third set to have no overarching plot of its own, being just endless variations on the same scene.

Beyond those structural complaints, it’s difficult to get much of a handle on Deadly Sanctuary. One doesn’t often encounter such a stew of the wildly inept and the earnestly ambitious. You should have at this point a fair sense of what Franco, Towers, and their collaborators were trying to accomplish, adapting the signature work of the world’s most disreputable author on what passed in their milieu for a grand scale, in a country whose rulers had an impressive track record of imprisoning or even murdering their own citizens on ideological grounds. In Spain, Deadly Sanctuary could legitimately claim to be a revolutionary film. However, it was not— indeed, obviously could not be— released in Spain so long as the Fascists remained in power. In the places where it did play (Italy, France, West Germany, Britain, the United States, etc.), it was little more than a tawdry sex-horror flick, and it got treated accordingly. Nor can I see much room to argue that that was unfair. Divorced from the context of Franco vs. Franco, Deadly Sanctuary just looks like a two-hour parade of sleaze, absurdity, and unforgettably bad acting. It is, in its way, an extraordinary achievement to get a performance this crude and junky from Mercedes McCambridge, so we should not be surprised to see the rest of the cast serving up a veritable banquet of ham and wood. Romina Power might as well be sleepwalking, Akim Tamiroff seems to think he’s playing Renfield in a very broad Dracula parody, and Klaus Kinski is at his kinskiest. The male supporting players give the impression that Baron Greenback’s cloning machine was left to run unattended while set to “Herbert Fux.” And Jack Palance is virtually indescribable. Drunk and out of control, he plays a character whose dialogue consists mostly of long, rambling speeches. Put the two together, and you’ll believe neither your eyes nor your ears. While Deadly Sanctuary may not deliver the specific form of weird and shitty that one learns to expect from Jesus Franco, it is to be cherished all the more for offering forms of weird and shitty all its own.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact