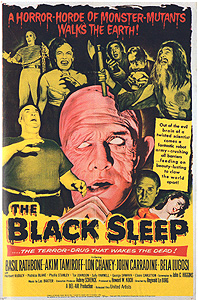

The Black Sleep (1956) ***

The Black Sleep (1956) ***

In 1959, mere months after the release of Plan 9 from Outer Space, United Artists circulated Invisible Invaders, a somewhat more expensive and considerably better movie on approximately the same premise. Curiously enough, that was actually the second time Ed Wood had been one-upped by an independent production distributed through the UA network. Three years before, his Bride of the Monster had been upstaged by The Black Sleep, another atypical throwback to the style of the early 1940’s featuring both Tor Johnson and Bela Lugosi. (In fact, The Black Sleep was the last film Lugosi lived to complete.) This can’t have been anyone’s deliberate intention— I mean, really, who the fuck would want to rip off Ed Wood?— but that very inadvertentness makes the phenomenon all the stranger. What might be weirder still is how The Black Sleep seems to stand poised between two eras of gothic horror, assembling a bunch of old has-beens to eulogize a genre that was ten years in its grave, even as two unrelated sets of European filmmakers were gearing up to bring it back to life.

London, October 1872. In a cell on Newgate Prison’s death row (although the establishing shot shows the Tower of London instead), disgraced physician Dr. Gordon Ramsay (Herbert Rudley) awaits his appointment with the gallows and subsequent transfer to the dissection lab at Surgeon’s Hall. The crime for which Ramsay is to die was the murder of a moneylender named Curry, to whom the doctor was deeply in debt. One has to wonder what sort of defense Ramsay mounted, for the case against him was weak in the extreme— Ramsay admits to quarrelling with Curry, but says he was knocked unconscious by a blow to the head from behind after only a few moments, and even the body Scotland Yard dragged out of the Thames was so badly mutilated and decayed that its identity as Curry’s has to be considered suspect. Nevertheless, the court allowed itself to be persuaded, and Gordon now has just hours to live. It is thus a small but welcome relief when he receives a visit from his mentor, Sir Joseph Cadman (Basil Rathbone, from The Magic Sword and Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet). Dr. Cadman has qualified good news for his old friend, in that he has convinced the presiding judge to rescind the dissection clause of Ramsay’s sentence, allowing him to have a decent, Christian burial under Cadman’s direction instead. He’s also smuggled in a little something to make the execution itself go a trifle easier, a dose of a rare Punjabi drug called Nind Andhera— the Black Sleep. If Gordon will take it tomorrow morning, he’ll go to the gallows completely insensible of anything going on around him.

Actually, Dr. Cadman is being even more devious than he’s letting on. Far from a simple narcotic, the Black Sleep places its users in a state of suspended animation outwardly indistinguishable from death with the diagnostic tools of the 19th century, and when the guards come to escort Ramsay to the hangman in the morning, it looks for all the world as though the prisoner has checked out early of natural causes. Cadman takes custody of the “body” as per his arrangement with the court, and he brings it to, of all places, a tattoo studio in Limehouse. The proprietor of this seedy establishment is a Gypsy by the name of Udo (Akim Tamiroff, of Deadly Sanctuary and Ursus and the Tartar Princess), who has often played Burke and Hare to Cadman’s Dr. Knox. Once all concerned are thus safely out of sight of the authorities, Sir Joe injects Gordon with the antidote he has devised for the Black Sleep. Ramsay is a bit befuddled at first, but he catches on quickly enough that Cadman has saved his bacon, and as ulterior motives go, the older doctor’s aims in doing so are readily acceptable to Gordon. While Udo heads north to give a proper Presbyterian burial to 168 pounds of gravel, Dr. Gordon Ramsay will be reborn as Dr. Ramsay Gordon, assistant and collaborator to Dr. Cadman at his converted abbey on England’s southeast coast. Cadman has a groundbreaking research project underway, and he’s reached the point where he desperately needs another well-trained medical mind and two more talented hands.

Cadman’s abbey turns out to be a classic gothic mad lab. Massive, spooky, 1000-year-old fortifications? Check. That part of the coast was subject to frequent Viking raids, so the monks— “who were not stupid men, and preferred to remain alive,” as Cadman eloquently puts it— turned the abbey into a castle fit for the most warlike of Medieval noblemen. Secret passageway concealing the laboratory proper from prying eyes? Check. A hidden door at the back of the fireplace in Cadman’s study communicates with a staircase to the top of the abbey’s highest tower, enabling the doctor to conduct his surgical investigations under the illumination of the tower’s huge skylight. Damaged loved one to motivate the mad scientist’s unsavory experiments? Check. Cadman’s much younger wife, Angelina (Louanna Gardner), has lain comatose and paralyzed for the last eight months, incapacitated by a malignant tumor deep in her brain. Sinister servant? Check. The first person Ramsay meets at the abbey is Casimir the watchman, a skulking mute whose “sinister” credentials come mostly from his being played by Bela Lugosi. Lugosi still just naturally looked like he was up to no good even when he was standing impatiently on death’s doorstep, waiting for the Reaper to answer his knock. Freakish monstrosity running loose in the shadowy corridors? Check. The second person Ramsay meets is Mungo (Lon Chaney Jr.)— formerly Dr. Munroe, of St. Thomas’s hospital— the brilliant surgeon turned demented strangler whom Cadman also hopes to cure with his discoveries. Good-looking women for said monstrosity to threaten in between scenes devoted to advancing the plot? Check. When Ramsay encounters Mungo, he’s chasing Cadman’s nurse, Laurie (Patricia Blair), down the hallway, and only the calmly commanding intervention of the other nurse, Daphne (Phyllis Stanley), stops Mungo from choking the life out of everybody in the abbey foyer. Even more freakish monstrosities locked up in a secret dungeon downstairs? Check— although we won’t be finding out about that part for a while yet.

So what’s Cadman working on up at Castle Frankenstein, you ask? Well, the thing about Angelina’s tumor is that her husband actually does have the skill to cut the malignancy out of her brain and patch her back up again. What he lacks is a sufficient understanding of the brain’s geography to perform the operation without risking unacceptable damage to any of her faculties. The last thing he wants is to have to tell Angelina, “Guess what, honey… I cured your brain cancer! Only you’ll never be able to taste anything ever again, and I’m pretty sure you have Tourette’s Syndrome now, too.” With that in mind, Cadman has been using the Black Sleep to enable him to perform exploratory open-brain surgery on living patients, and observing the effects of galvanic stimulation on the various regions of their cortices. Of course, this being a horror movie, Sir Joe isn’t terribly picky about securing the consent of his experimental subjects before he operates, nor is he bothered much if a stray stroke of the scalpel short-circuits, say, Casimir’s speech center. Ramsay gets his first inkling of this when what he took to be the cadaver he and Cadman were using for their initial tag-team experiment begins leaking fresh cerebrospinal fluid after Cadman starts digging into its Fissure of Rolando. Dead brains don’t do that, and Gordon is taken more than a little aback at this revelation of exactly how his mentor (and rescuer— let’s not forget that) conducts his research. More of the pieces fall into place when Laurie slips a note under Ramsay’s door, asking him to come see her as soon as possible. Laurie, it turns out, is Dr. Munroe’s daughter, and while it may be true that Cadman intends to use what he is learning to repair the lunatic’s higher mental functions, it also just happens to have been Cadman who turned Munroe into Mungo in the first place by botching an operation meant to overcome the stroke-related paralysis of the left side of his body. There have been other human experiments, too— at least two of them— but Laurie has no idea what became of the men after Cadman got through with them. Nor is the doctor himself at all forthcoming about what happened to that sailor (George Sawaya, from The Devil’s Rain and Hands of a Stranger) whom he and Ramsay had been working on together.

Udo, meanwhile, is in the process of rounding up yet another guinea pig. This one is to be a woman (The Son of Dr. Jekyll’s Claire Carleton), and Ramsay happens to hear the Gypsy mention that she was the mistress of the “enormous” fellow whom he brought around earlier. Cadman remembers the one, right? That moneylender? Wait— did Udo just say moneylender? Yes, that’s right. We’re talking about none other than Curry, the man Ramsay was convicted of murdering! And since Cadman doesn’t seem to be killing his research subjects, that means there’s every possibility that Curry is somewhere in the abbey even now. Gordon goes to Laurie with what he has found out, and she agrees to help him find Sir Joe’s hidden recovery room. Cadman isn’t going to like that, of course, but that might not be such a big problem. After all, the chances are that Curry (Tor Johnson, from The Unearthly and The Beast of Yucca Flats), the sailor, and the other two experimental subjects (John Carradine, of The Cosmic Man and The Incredible Petrified World, and Sally Yarnell) aren’t too fond of Cadman at this point, either, to say nothing of those cops who just barely miss catching Udo in the act of abducting the doctor’s next intended victim.

I seriously doubt that either director Reginald Le Borg, screenwriters Gerald Drayson Adams and John C. Higgins, or producer Howard W. Koch had any idea what was on its way from Britain and Italy while they were making The Black Sleep. The Curse of Frankenstein and The Devil’s Commandment were both in some phase of production at roughly the same time as this film, but even if the creators of The Black Sleep knew about those movies, they could hardly have anticipated the magnitude of the coming gothic revival. In a sense, The Black Sleep is thus an illustration of the hazards of being at the forefront of something big— too far to the fore, and you miss your shot just as surely as the stragglers. On the other hand, it’s also worth asking why The Black Sleep itself did not trigger the craze touched off by Hammer’s only slightly later horror films. I mean, how much difference could one year really make? Most likely, this movie was simply too retrospective for its own good. Neither Hammer nor their Continental counterparts were content merely to blow the dust off of Frankenstein’s laboratory and hope for the best. Hammer used color cinematography; the producers of the present film did not. Hammer endeavored to make stars out of two capable but previously little-appreciated actors, much as Universal once had with Boris Karloff and (to a somewhat lesser extent) Bela Lugosi; Koch and company larded The Black Sleep’s cast with formerly big names whose glory days were well behind them, yet gave none of them save Basil Rathbone much of anything to do. The European gothics of the late 1950’s traded heavily on a then-unprecedented openness regarding gore and eroticism; The Black Sleep is bloodless and demure by comparison. Looked at from that perspective, it isn’t terribly surprising that this movie didn’t have what it took to woo audiences away from the more technologically-minded fright films that had dominated the decade thus far.

Old-fashioned as it is, however, The Black Sleep still gets the job done at least as well as most of the movies to which it hearkens back. Most notably, it crystallized a vague sense I’ve had for some time now that it’s too bad Rathbone got pigeonholed so early on as Sherlock Holmes. He had a commanding elegance about him akin to that later displayed by Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and which nobody else on the 30’s and 40’s horror scene could match. Lionel Atwill and John Carradine came close on occasion, but Atwill was always a little too foppish and Carradine a little too homespun to play the depraved Old World nobleman with Rathbone’s authority; neither of them would have been up to the challenge of Tower of London’s Richard III, for example. As Joe Cadman, Rathbone simultaneously prefigures the Cushing Frankenstein, and hints at all the brilliant mad movie scientists that might have been if only Rathbone hadn’t been so busy chasing Nazi agents all over the English moors during the years of the second Hollywood horror boom. He might even have injected some unwonted class into a Monogram or PRC production! The rest of the cast doesn’t quite match up to the top-billed star, but most of those who are required to do any actual acting (which is to say, not Tor Johnson, Bela Lugosi, or Lon Chaney Jr.) acquit themselves respectably well. Another thing The Black Sleep does right is to incorporate a bit of defensible real-world science into the mad variety more familiar from movies of its type. Much of the film’s horror stems from the certainty that attempting such delicate neurological investigations with the clumsy and invasive techniques of the late 19th century really would produce monstrous derangements of brain function, even if these specific symptoms (John Carradine’s character is convinced that he’s Bohemond of Taranto— the hell?) are not always especially plausible. Finally, Udo the Gypsy, who in most horror films of this era would be nothing but a comic relief character, is portrayed in much too sinister a light to become as irritating as one might anticipate. His clowning creates more unease than anything else, for it is plainly but a cover for a complete absence of conscience. All in all, The Black Sleep represents a commendable effort to bring some seriousness of purpose back into the gothic mad scientist movie, which had grown silly enough on its own over the years that it hadn’t really needed Abbott and Costello to poke fun at it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact