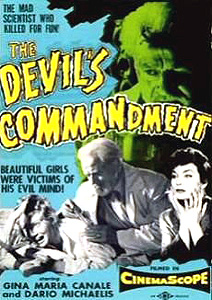

The Devil’s Commandment / Lust of the Vampire / The Vampires / I Vampiri (1956) ***½

The Devil’s Commandment / Lust of the Vampire / The Vampires / I Vampiri (1956) ***½

World War I and its attendant economic dislocations virtually destroyed the Italian movie industry. What had been one of the world’s foremost national cinemas, inspiring filmmakers around the globe with the scale of its ambition and its unparalleled mastery of sheer spectacle, was reduced to such straits that the country’s 3000-some theaters could find almost literally no homegrown product to exhibit by 1920. American and German studios were eager not only to fill the gap, but to perpetuate their advantage in the Italian market by forcing terms on exhibitors that made it nearly impossible for those few locally-produced films that did get made to secure profitable bookings. Not surprisingly, the arch-nationalist Fascist government that came to power in 1922 found this situation intolerable. The protectionist policies they implemented ran the gamut from crude (like quota systems and state financing buy-ins) to ingenious (like the rule requiring that all imported foreign films be dubbed into Italian at the original producer’s expense), but the aggregate result was Italy’s transformation by the mid-1930’s into a sort of cinematic hermit kingdom. Restrictions on imports meant that the vast majority of movies shown in Italian theaters originated within the country, while restrictions on exports (designed to manage Italy’s public image abroad) combined with other nations’ retaliatory trade practices to ensure that Italian films would be little-seen anywhere else. Hermit kingdoms can be very prosperous, though, and Italy’s movie industry did well under Fascism. Some 700 films were produced between 1922 and 1943, and Mussolini’s government footed most of the bill for constructing the giant Cinecitta studio complex, which opened in 1937. Quite a turnaround for an industry that was justly assumed to be moribund.

Of course, all that support and protection came at a price. Italian Fascism was authoritarian rather than totalitarian (which is to say that it merely demanded obedience, in contrast to the Nazis’ striving after actual thought-control), but the grip of its media censorship was firm just the same. Criticism of the regime was out of the question, naturally, but so were some other areas of subject matter that one wouldn’t necessarily expect. Most notably, the Fascists were obsessed with the idea of realism in art, not just in the usual right-wing sense of disliking the various modern abstract movements, but also in one resembling the contemporary Soviet loathing for material that might encourage the persistence of peasant superstition. As applied to film, the Fascist demand for realism meant a focus on the present day. It meant the channeling of escapist sentiment into forms based on wealth and social status, and away from pure fantasy. And most directly relevant to our purposes here, it meant a straight-up ban on horror movies. Italy hadn’t been a big producer of those anyway, but there had been a few during the silent era. I’m not certain exactly when the ban took effect, but it was definitely operative by the early 1930’s, when Italy was conspicuous by its absence among the cinematically important countries embracing or at least experimenting with the newly popular genre. Even Nazi Germany produced at least one horror film during the 30’s, but Italy? Zip, zero, zilch.

Interestingly, the fall of Mussolini and the end of World War II didn’t result immediately in a reaction against the artistic ideas of the Fascist period, and an almost cultish devotion to realism continued to hold sway among Italian filmmakers until well into the 1950’s. To the rest of the world, unacquainted with two decades’ worth of trends in Italian cinema, “neo-realism” looked like a groundbreaking new development, but the neo-realists were merely doing by choice a more extreme version of the things they’d been pushed to do under il Duce. The backlash against realism did finally come, however, and one of its leaders was Ricardo Freda. Freda is a curious figure. I know him mainly as the mentor of Mario Bava, and as the director of The Devil’s Commandment, Caltiki, the Immortal Monster, and the Dr. Hichcock movies— and therefore as someone of pivotal importance for the early evolution of Italian horror cinema. Freda didn’t care about horror movies, though— not in and of themselves. He turned to horror because he was sick to death of realism, and horror was the least realistic genre he could think of. Freda relished the opportunity that horror movies offered to do something bizarre, something surreal, something outlandish. There’s some irony in that with regard to The Devil’s Commandment, for in retrospect the most distinctive thing about this film as compared to later spaghetti shockers is its relatively scrupulous attention to questions of plausibility. Its horror is science-fictional and psychosexual, rather than supernatural, and more importantly, it invests almost as much energy in establishing motivations and tying up loose ends as the whole following decade’s corpus of Italian fright films put together.

There’s a killer on the loose in Paris. He preys on young women, and the nearly bloodless condition of the victims’ bodies when the authorities fish them out of the Seine has led the press to dub him “the Vampire.” Inevitably, Inspector Chantal (Carlo D’Angelo, from Hercules Unchained and Battle of the Worlds), the lead cop on the case, has been stuck at square one since the first corpse was discovered. Equally inevitably, Chantal has a gadfly and self-appointed rival in newspaper reporter Pierre Lantin (David Michaelis, of The Mad Butcher and The Day the Sky Exploded), whose main professional ambition at present seems to be to crack the Vampire case before the police. Lantin, meanwhile, has a pest of his own, although she interferes merely with his personal life. That pest is named Giselle du Grand (Gianna Maria Canale, from Hercules and Goliath and the Vampires), and she’s the niece of the duchess who was once similarly obsessed with Pierre’s father. Lantin’s friend and coworker, Ronald Fontaine (Angelo Galassi), finds Giselle quite charming, but Pierre just thinks she’s creepy, and wishes she would stop stalking him.

It might seem that we’ve seen the Vampire in action when actress Nora Duval (Ronny Holiday) is abducted from her theater dressing room by Joseph Signoret (Paul Muller, from Lady Frankenstein and Venus in Furs). In fact, however, Signoret is but a cog in a fairly complex criminal machine. He’s a heroin addict, and the real Vampire— or more accurately, Vampires— have been using his affliction to lever him into taking all the risks associated with procuring victims. Of course, dope fiends are not notoriously reliable, and this time, Signoret has left a trail. Not only has he allowed himself to be photographed following Nora, but some of the missing girl’s friends saw him often enough to remember him, and to describe him when Lantin sees the aforementioned photo, and goes to interview them. One of those friends, a girl named Lorette (Wandisa Guida, of Maciste in King Solomon’s Mines and The Vengeance of Ursus), even thinks she knows the apartment where Signoret lives. Following up that lead yields mixed results. Latin does indeed encounter Signoret and recognize him from the photograph, but the junkie is able to trick him into leading Chantal and his men to the wrong flat later on, and thereby discrediting himself. That close call convinces Signoret that he’s had enough of this Vampire shit, and he goes to extort terms for an exit from his employer. That would be Dr. Julian du Grand (Antoine Balpêtré, from The Hands of Orlac and Fantomas Against Fantomas), prominent medical researcher and cousin to the duchess of the same name. Du Grand’s bacon is saved by his hulking lab assistant (Renato Tontini), who strangles Signoret when the confrontation between him and the doctor looks apt to turn violent, but a certain amount of damage has clearly already been done. If Signoret has been found out, then it’s only a matter of time before his ties to Dr. du Grand are discovered, too. In that case, there’s nothing else for it. Julian du Grand will simply have to disappear— and what better way to disappear than by faking his own death, and substituting Signoret’s corpse for his during the closed-casket funeral?

Well, now we know who has been killing all those young women, but it isn’t yet apparent why. For that, we’ll have to take a closer look at Giselle du Grand and her aunt, the Duchess Margherita. As in, close enough to notice that they’re played by the same actress. That’s right— the two ladies are really the same person, and the blood of all those dead girls has been the starting point for the drug whereby Julian artificially restores Margherita’s youth for a few weeks or days or hours at a time. The reason he does so is that Julian has been in unrequited love with the duchess ever since they were both the age that she appears to be when posing as Giselle. Unfortunately, the effects of Julian’s youth serum are not only temporary, but less long-lasting each time Margherita injects it. (Signoret could have told her all about that, if she’d ever thought to ask him…) Julian does have a line on something more permanent, but it needs a lot more work. That means more victims, which at the moment is just as well, really. After all, Lorette might not have told Lantin everything she knows, and it really wouldn’t do for her to talk to Chantal. If the killers have to dispose of her anyway, they might as well get some use out of her, right? The trouble is, the duchess is just plain unreasonable about the whole business. Her desire to be young all the time, even if that means shooting up like Dee Dee Ramone with the suboptimal drug Julian already has, takes precious resources away from the very studies that might let him restore her once and for all. Furthermore, getting the raw material for those short-term rejuvenations exposes the conspirators to the risk of discovery each time— a problem which has just become more serious now that Signoret is out of the picture. Meanwhile, “Giselle” keeps chasing after Pierre, who is hunting the Vampire at least as determinedly as the cops, and much more successfully so far. If she can’t control herself, Margherita is going to be her own undoing.

The most immediately astonishing thing about The Devil’s Commandment is how many earlier movies it manages to reference, riff on, and borrow from over the course of its fairly compact running time. It’s like Ricardo Freda decided to make in one go all the horror films that he and his countrymen hadn’t been permitted to during the 30’s and 40’s. Look closely, and you’ll spot nods to Murders in the Rue Morgue, Doctor X, The Vampire Bat, The Mystery of the Wax Museum, The Walking Dead, The Man They Could Not Hang, The Human Monster, Chamber of Horrors, and The Corpse Vanishes, together with production design suggesting a mad amalgam of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Black Room, and The Curse of the Cat People. Yet despite all that, The Devil’s Commandment does not come across as a mere composite rip-off. No doubt that’s partly because the sheer breadth of its borrowing precludes the lifted elements being used in quite the same way as they had been originally. A platypus, after all, is a great deal more than just a beaver with a duck’s beak, a sea turtle’s reproductive system, and a centipede’s claws.

This movie has other virtues, though, that can’t be accounted for by the novelty of many unrelated things being copied at once. The Devil’s Commandment also exhibits a maturity and sophistication with regard to psychological and social issues that is truly shocking in light of subsequent Italian horror films. The behavior and motivation of the characters is extremely well drawn, and everybody with more than a line or two is allowed a rare degree of personal complexity. What’s more, none of these folks are limited by the usual rote developmental arcs associated with their story functions. Inspector Chantal turns out not to be the bumbler we initially take him for. Pierre never falls for “Giselle,” no matter how hard she pushes him— and even more incredibly, he doesn’t fall for Lorette, either! Ronald rises above his station as comic relief in an exceptionally satisfying way (although doing so costs him dearly). Dr. du Grand and his assistant, despite their plainly increasing ambivalence toward what Margherita demands of them, don’t have the usual change of heart at the climax. The most impressive thing, though, might be the honesty with which Joseph Signoret’s drug addiction and the tangled web of thwarted sexual desire radiating out from Margherita are portrayed. These are adult themes handled in an adult manner, and for all Freda’s rebellion against neo-realism (or paleo-realism, for that matter), I think what we’re seeing here is the habits of that mode of filmmaking imposing themselves. Frankness about the… well, realities of sex and vice is one of the hallmarks of Italian realist cinema, and it was wise of Freda to hold onto that even in what he intended as a maximally unrealistic film.

And then there’s Freda’s secret weapon to consider: cinematographer Mario Bava. Bava would later become Italy’s first true master of horror cinema, and he’s unmistakably a talent to look out for even here. He was one of those rare cinematographers who weren’t just equally adept with monochrome or color film, but who could create black-and-white images deserving of colorful adjectives like “vivid” and “lush.” The Devil’s Commandment is every bit as beautiful as Black Sabbath or Kill, Baby… Kill!. More remarkably, though, it’s beautiful in many of the same ways, even though it seems intuitively like that shouldn’t be possible, technologically speaking. Later in his career, Bava was famous for using colored lights and filters to create a look of dreamlike hyper-reality, and he somehow achieves something comparable here, even though no color information is discernable on the screen. That’s an odd way to put it, I realize, but I chose my words for a reason. Color effects like those Bava used later can alter the appearance of images captured on monochrome film, and The Devil’s Commandment contains clear proof that Bava understood that principle well. Several times, we see Giselle du Grand age into Margherita before our eyes, without recourse to the clunky dissolves used to similar purpose in movies like Atom-Age Vampire and The Man and the Monster. Instead, Duchess du Grand’s transformations employ a technique made famous by Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which successive layers of colored makeup are revealed by cycling through combinations of lighting and filters that variously emphasize them or cancel them out. It seems more than plausible that Bava exploited the sensitivity of black and white film to colored light in other, less conspicuous ways as well.

Another Bava talent that The Devil’s Commandment prominently displays is his appreciation for the forms and textures of a set, honed by his background as a painter. Bava could always find a room’s most interesting angle, or a frame composition laden with subliminal thematic messages, and those abilities are in full effect here. He also shows off his gift for in-camera special effects with some lovely Paris street scenes that prove, upon close examination, to have been created on the studio lot using matte composition with still photos and occasionally even full-scale blow-ups of elements like a line of ironwork fencing or an architecturally distinctive doorway. Tricks of that sort not only make The Devil’s Commandment more engaging to look at, but also strengthen the story by echoing its emphasis on deceptive appearances and hidden significance. This may be mostly Freda’s show (although Bava did take over direction for the final two days of shooting), but Bava’s genius undeniably elevates it to a level his patron would most likely not have achieved without him.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact