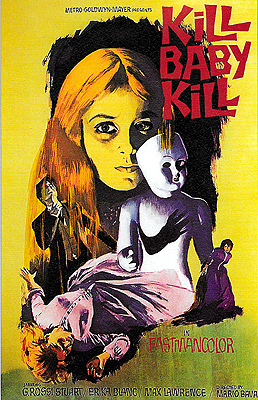

Kill, Baby… Kill! / Don’t Walk in the Park / Curse of the Dead / Curse of the Living Dead / Operation Fear / Operazione Paura (1966/1968) ***˝

Kill, Baby… Kill! / Don’t Walk in the Park / Curse of the Dead / Curse of the Living Dead / Operation Fear / Operazione Paura (1966/1968) ***˝

If any of them are still living, I hereby call down bitchslaps upon all of the people who came up with the various titles under which this movie has been shown over the years. The original Italian title, Operazione Paura (“Operation Fear”), sounds like one of the vast numbers of shitty James Bond wannabes that were spewing forth from Continental Europe at the time it was made. Kill, Baby… Kill! sounds like a tragically hip giallo, while the late reissue title Don’t Walk in the Park sounds like the world’s stupidest Last House on the Left rip-off. Meanwhile, Curse of the Dead and Curse of the Living Dead both sound like relatively dismal post-Romero zombie movies. But Kill, Baby… Kill! is none of those things. Instead, it is one of Mario Bava’s finest and most influential gothics, and is almost certainly the most visually stunning movie he ever made.

You’re going to spend most of this movie’s running time confused. That’s alright— you’re supposed to feel that way. In some creepy, decaying castle in the countryside of one of those generically Germanic lands without which the gothic horror film simply could not exist, a young woman who we will later learn is called Irena Hollander (Mirella Pamphili, from 2+5 Mission Hydra and The Sweet Body of Deborah) falls to her death on the spikes topping the iron gate some three stories below the catwalk where she’d been standing. A small child in a white dress laughs at Irena’s fate, and then walks off into the misty night.

Evidently Irena’s death is only the latest of a long string of mysterious demises in the neighborhood, because whatever government it is that holds ultimate responsibility for law and order around the place has dispatched one Inspector Kruger (Piero Lulli, of Maciste Against the Sheik and Fury of Achilles) to the village overlooked by that castle with instructions to get to the bottom of it all. Neither the villagers nor their burgermeister (Luciano Catenacci, from Short Night of the Glass Dolls and In the Folds of the Flesh) are being particularly helpful, and Kruger has decided to get tough. To that end, he sends for a coroner named Dr. Paul Eswai (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart, of Caltiki, the Immortal Monster and The Last Man on Earth) to perform an autopsy on the deceased Miss Hollander whether the locals like it or not. As a matter of fact, they like it so little that several men sneak Irena’s body out to the cemetery and attempt to bury it before Dr. Eswai can get a look at it, but Kruger catches them in the act and puts a stop to that foolishness.

Eswai performs his autopsy, with the aid of a local woman named Monica Schuftan (Erika Blanc, later of The Devil’s Nightmare and The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave), who has also only recently arrived in town— though she was born there, and her parents were servants at the castle, she hasn’t set foot in the place for nearly twenty years. What they find is curious indeed. Somebody has inserted a small silver coin into the dead girl’s heart. Eswai is stumped, but Monica thinks she knows what’s going on; there’s a saying in these parts which has it that a coin in the heart is the only way to prevent those who die by violence from returning as malevolent ghosts. And if that’s the case, then it’s safe to assume that the villagers don’t believe any more than Kruger does that Irena’s deadly fall was an accident.

That particular superstition also goes some way toward explaining why the townspeople have been so eager to prevent Eswai’s autopsy, which could be counted upon to end with the prophylactic coin’s removal, along with why they’re so upset about it now that it has come to pass. Even so, the form that upset takes— an attack on Eswai by two men armed with knives on the street that night— seems just a bit excessive. The only reason the doctor makes it back alive to the inn where he’s staying is because his assailants are driven off by the command of a black-clad woman (Fabienne Dali, from Touch of Skin and The Libertine) who disappears before Eswai has a chance to say one word to her. She turns up again a little later, though, and at the inn, of all places. As Paul discovers when he eavesdrops from the doorway linking the public dining room to the kitchen, his rescuer’s name is Ruth, and she has a reputation as a white witch. The innkeeper (Guiseppe Addobbati, of Watch Me When I Kill and Nightmare Castle) and his wife (Franca Dominici) are very concerned about their daughter, Nadienne (Micaela Esdra), who claims to have seen “her” and been marked for death thereby. Ruth performs a strange and rather painful-looking ritual on Nadienne, and tells her that if she sleeps with her torso wrapped in a hideously thorny sort of creeper called a “leech vine,” then she will be protected against whatever it is that she’s afraid of.

Meanwhile, Inspector Kruger has come to the conclusion that the answers he seeks are all up at the castle, and he goes there to see the Baroness Graps (Gianna Vivaldi), sending word to the inn that Dr. Eswai is to follow as soon as he is available. Kruger isn’t there, though, when Eswai arrives at the Villa Graps, and the baroness claims not to have seen him before ordering Paul out of her house. While he is in the process of leaving, however, Eswai encounters a seven-year-old girl named Melissa, who teases him with a vanishing act after leading him down to the castle’s basement. Paul doesn’t notice the portrait on the wall marked “Melissa Graps, 1880-1887” when he passes by it in pursuit of the little girl, but we sure do.

Paul Eswai isn’t the only one having a run-in with little Melissa that night, either. Back home, Monica is tormented by unsettling dreams involving both the girl and an eerie porcelain doll, and when she awakens with a start, the doll from her dreams is lying at the foot of the bed, staring up at her with its stained glass eyes. Monica understandably figures she’d be better off sleeping somewhere else, and when she encounters Paul on his way back from the villa, he gets her a room at the inn. While they’re waiting for the innkeeper’s wife to get the room together, Paul and Monica hear at last what the villagers think their problem is. About 20 years ago, Melissa Graps died— apparently in an accident— at the foot of the bell tower of the village church, and the town has lain under a curse ever since. The little girl’s spirit roams by night, and anyone who lays eyes on her will bleed to death like she did before the next sunrise. Eswai doesn’t believe a word of it, naturally, and he envisions a rather more mundane explanation when Inspector Kruger turns up dead in the cemetery that night. But it isn’t so easy to explain away what happens when, one by one, the people to whom Paul and Monica turn for answers have visions of Melissa Graps and then cut their own throats in a trance.

If it weren’t for its weak ending, Kill, Baby… Kill! would be easily the best of the 60’s Italian neo-gothics. The film offers a textbook example of the right way to go about keeping an audience in the dark regarding what’s really going on, and might fairly be described as the altar at which nearly every subsequent movie about a wicked juvenile ghost worships. Even Hideo Nakata’s Ring seems to contain a couple of faint echoes of Kill, Baby… Kill!. Melissa Graps is one of the screen’s all-time great evil innocents, even despite the fact that she really doesn’t do much of anything. What makes her work is that she exemplifies an age-old bit of ghost-lore that turns up all too infrequently in the movies— that ghosts, as insubstantial beings, are able to harm others only by causing others to harm themselves. It sounds like nonsense— a mistake in the dubbing, even— when he says it early on, but it is a chilling moment when it suddenly comes clear what the burgermeister meant when he told Inspector Kruger that Irena Hollander’s death on that iron gate was neither murder, nor accident, nor suicide.

Technically speaking, Kill, Baby… Kill! probably marks the apex of Bava’s career as a director. It is a gorgeous, engrossing movie, with more sheer style by orders of magnitude than all of Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations combined. Some of the camera tricks are a bit heavy-handed, but I have only rarely seen a film that makes such use of the full depth of frame, or in which such careful consideration was given to the frantic camera movements that are the signature feature of the Italian gothic. It may look like random chaos at first glance, but Bava definitely knew what he was doing— not even the close-cropped pan-and-scan print that I saw could disguise how well most of the shots in this movie were composed. Furthermore, it’s amazing to me how much suspense Bava manages to wring out of so many scenes in which essentially nothing is going on. The production design is also brilliant, balanced perfectly between the real and the surreal; this may well be the best sinister village set since the one Hans Poelzig designed for The Golem back in 1920. All in all, it’s enough to make the wobbly ending twice as frustrating as it would have been in a lesser movie— which should not be taken to mean that Kill, Baby… Kill! isn’t totally worth checking out anyway!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact