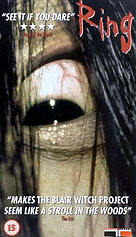

Ring / Ringu (1998/2003) ****

Ring / Ringu (1998/2003) ****

It isn’t often that a novel which proved only marginally successful upon its initial publication takes sufficiently strong root in the long run to give rise to a full-blown intercontinental pop-culture phenomenon. That is exactly what happened with Koji Suzuki’s weird-ass sci-fi ghost story, Ring/Ringu, however. When it was released in hardcover in 1991, Ring was a mediocre performer in the marketplace, although it did fare well enough that its publishers went ahead and issued it in paperback a little while later. By that time, the fickle mechanism of word-of-mouth buzz seems to have kicked in, because the paperback edition sold very well— well enough, in fact, that Ring began to sprout spin-offs in 1995. That year saw the publication of Rasen, the first of three sequels to the original novel. (The title means “Spiral,” by the way; it’s the only one of the books for which the title is in Japanese.) It also saw the premiere of a 95-minute movie-of-the-week adaptation produced by Fuji-TV. By most accounts, the Fuji-TV Ring was relatively faithful to the novel (at least in comparison to what would come later), but not especially well made. It was, however, immensely successful, and late in 1996, it was released to home video as Ringu: Kanzen Ban (Ring: The Complete Edition), the expanded title indicating the restoration of a few scenes of sexual content which had been judged too graphic for television broadcast even in Japan.

That was the year Ring mania really started to gather momentum. Along with the story’s first appearance on home video, 1996 also marked the first branching out of the franchise into the medium of comics, when Kojiro Nagai’s manga adaptation appeared. Then, in 1998, Suzuki wrote Rupo (say “Loop” with a really thick Japanese accent, and what do you get?), the third novel in the series. At the same time, a pair of production companies called Asmik Ace and Omega Entertainment, emboldened by the brisk sales of Ring: The Complete Edition, secured the rights to make honest-to-God movie versions of both Ring and Rasen— so emboldened were they, in fact, that they arranged to release the two movies simultaneously, and even as a double bill on opening night! (It was necessary to hire two different creative teams to pull this trick off, and Ring was directed by Hideo Nakata, while Joji Iida took on Rasen.) It was in 1999 that the floodgates really opened, however. On the print front, Suzuki wrote still another book, Birthday, this one a collection of short stories intended to fill in some of the gaps in the story arc formed by the three novels. A manga version, illustrated by Meimu, appeared almost immediately, along with similar adaptations of Rasen (by Mizuki Sakura) and the Hideo Nakata Ring movie (by Misao Inagami). Meanwhile, Nakata— who was disgusted at the way Iida’s version of Rasen turned out— went back and made his own sequel, under the title Ring 2 (which Meimu also redacted into manga form). Ring 2 was intended from the start to take the story in an entirely different direction from Suzuki’s novels, and at least five separate screenplays were considered. After the movie was released, the four runner-up scripts were published together in book form as Ring: Four Scarier Tales. Then there were the TV series. First came “Ring: The Final Chapter,” which despite its title went back to the beginning and retold the original story yet again, changing it significantly in a number of perplexing ways. Immediately after that show’s twelfth and final episode aired, a TV version of Rasen was launched, which followed the contours of the plot as told in the book, manga, and movie only very loosely— those who have seen it report that the thirteen-episode “Rasen” series owes more to “The X-Files” than to its supposed source. Also in 1999, the Ring phenomenon spread across the Sea of Japan into South Korea, where Nakata’s film version was remade as The Ring Virus. Obviously such a frantic pace could not continue for long, and the craze started to wind down in 2000; Ring-related activity that year was limited to the release of the prequel, Ring 0: Birthday (derived from one of the stories in Suzuki’s Birthday), and a Meimu-illustrated tie-in manga for the latter film. (At some point, there was also a Ring radio drama, but I have been unable to discover anything about it beyond the bare fact of its having been made.) Even then the epidemic hadn’t quite run its course yet, for one more remake was still to be shot, this time in America. It did surprisingly well, even in the hard-to-please cult-film market, and the inevitable sequel to Hollywood’s The Ring finally appeared in 2005 after a lengthy and rather vexed period of development.

Of all the many Ring movies, however, there is one that broad consensus singles out as the best of the bunch: Hideo Nakata’s version from 1998. After all, it was this interpretation— and not Koji Suzuki’s novel or the TV movie from 1995— that both subsequent remakes took as their main source material. There is good reason for this. Nakata’s version diverges substantially from the story as Suzuki originally told it, and none of the earlier variants are nearly as satisfying. The sci-fi angle of the original is buried here until it is almost completely invisible, hinted at solely by the odd manner in which the supernatural villain operates. The personalities of several major characters have been changed considerably, as have the relationships between them— a happily married man, for example, has become a divorced woman in this retelling, and his longtime friend with a sinister secret is here transformed into her unreliable but upstanding former husband! The modus operandi of the evil force is also notably different, and at least one hard-hitting horror set-piece has been invented out of whole-cloth, having featured in none of the previous iterations. In short, the story of Ring as most current fans know and love it is almost entirely the creation of Nakata and screenwriter Hiroshi Takahashi. Let’s take a look now at what they have to show us...

It’s late on a Saturday evening, and two teenage girls (Yuko Takeuchi and Doppelganger’s Hitomi Sato) are hanging out, doing what teenage girls usually do— chatting and trading the latest gossip. Masami’s gossip is more exciting than Tomoko’s. She’s heard from some kids at another school about a family that had a strange and frightening experience when they went down to Izu for a vacation recently. One of the children apparently wanted to videotape a favorite television show while he was out playing in the woods, but forgot that the TV channels in Izu weren’t the same as those in Tokyo. Instead of the static that should have been on the tape when he played it back, though, there was the image of an evil-looking woman, who said that anyone who watched the tape would die in exactly one week. The moment the tape ended, the telephone rang, and when the boy picked it up, a female voice hissed, “You saw it!” and hung up. Tomoko falls strangely silent when Masami finishes telling her tale; the details don't match up, but on the whole, it sounds a lot like something that really did happen to her and her friends just last weekend. They really did go to Izu, and they really did watch a peculiar videotape while they were there. There wasn’t any spectral woman making overt death-threats, but the disjointed series of images— a man looking down a dark, cylindrical shaft, a woman combing her hair in an oval mirror, men crawling in slow motion over barren ground, an eye with the kanji “sada” (“chaste”) reflected in it, a jumble of words in which “eruption” stands out prominently, a decaying well in a woodland clearing— were plenty eerie enough. And while no one was on the other end of the line when Tomoko answered, the phone did indeed ring right when the last image on the tape faded to black. That was a week ago— a week ago today, as a matter of fact. And as the two girls are about to find out, Masami’s version of the story has more than a little truth to it.

Masami isn’t the only one talking about a cursed videotape, either. The legend is making the rounds of secondary schools all over Tokyo, to the extent that even the media have taken notice. Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) is a reporter for a TV news magazine, whose number-one job of late has been interviewing teens and pre-teens about the subject of the demonic tape. Reiko doesn’t realize this yet, but the story she’s covering has an uncomfortably strong personal relevance to her— Tomoko, whose mysterious death has been officially attributed to a freakish early heart attack, was Reiko’s niece. When Reiko and her young son, Yoichi (Rikiya Otaka), attend the girl’s wake, Asakawa overhears some of Tomoko’s friends talking about how she wasn’t the only one to die that day. If these girls are to be believed, all three of the friends with whom Tomoko went on her final weekend outing died, too— at exactly the same moment as Tomoko, even though they were all separated by a distance of many miles at the time. Furthermore, Masami is said to be locked in a mental hospital now; among her more curious symptoms is a violent aversion to TV sets. But most importantly, Tomoko’s friends are all in agreement that she and her three dead buddies were victims of the notorious evil video.

Reiko checks up on the details of what she heard at the wake, and every element of the girls’ story seems to be more or less legit. She also turns up the name of the resort where the doomed kids stayed the week before their deaths by examining the set of photos Tomoko took while she was there. With her stake in the mystery now personal instead of merely professional, Reiko sets off for Izu Pacific Land, and has a look around the cabin in which Tomoko stayed. She turns up nothing of value, and at first it looks like her questioning of the man running the desk at the rental office is going to be a washout too. That’s when she happens to notice the rack of VHS tapes against the wall beside the desk, one of which is, oddly, not in the usual colorfully labeled box. Reiko takes the misfit tape back to the cabin and watches it. No doubt about it— this is the fabled cursed video. The phone rings, of course, and when Reiko puts the receiver to her ear, the only sound on the other end of the line is a strange, high-pitched hum exactly like the soundtrack to the tape. Congratulations, Reiko... Hope you enjoy your curse.

The first person Reiko turns to is her ex-husband, Ryuji Takayama (Hiroyuki Sanada, of Message From Space and Black Magic Wars). Ryuji is a math professor at a university somewhere in Tokyo, which would seem to make him not the logical choice for assistance in such a situation, but Reiko knows something we don’t. Ryuji also possesses formidable powers of clairvoyance and mind-reading, and is thus more likely than the average mathematician to take the paranormal seriously. (One assumes that it is from Ryuji that Yoichi inherited his own budding psychic abilities, which are going to get him in a lot of trouble later.) Whatever led to the breakup of the marriage, it was obviously not a shortage of love on Ryuji’s part, for no sooner has Reiko explained her predicament to him than he pops the copy of the deadly video that Reiko made into his VCR and watches it himself, at the risk of his own life if his ex is right about the effect of doing so. The phone doesn’t ring this time, but something tells me Ryuji is fucked anyway.

Following the various indistinct clues they are able to extract from the tape, Ryuji and Reiko begin digging frantically into the mystery of its origins, reasoning plausibly that by doing so they will turn up a way to avert their prescribed fate. (And incidentally, there’s a very good reason why I list Ryuji’s name first. In contrast to the more recent US version, the 1998 Ring has Reiko distinctly taking the back seat to her former husband in their quest for answers. Could it be that the Japanese still aren’t quite ready for a strong, independent female lead?) They get an additional boot in the ass on their mission when Tomoko’s spirit appears to Yoichi, and convinces him to watch the video too. (See? I told you the boy’s second sight would prove to be more trouble than it was worth.) Their investigations lead them to a tiny village in the shadow of Mount Mihara, where a woman named Shizuko Yamamura (the apparently surname-less Masako) once lived. Shizuko claimed to be a precognitive psychic, and once predicted a devastating eruption of the volcano. Her subsequent career as an experimental subject for a scientist named Heihachiro Ikuma (Daisuke Ban, from “Android Kikaider” and “Battle Fever J”) led only to tragedy and disgrace, however, and she committed suicide by leaping into Mount Mihara’s caldera sometime in the 1960’s. Shizuko did have a daughter, a girl by the name of Sadako (Rie Inou), although nobody really seems to know what became of her after her mother’s death. I’ll tell you this much: It wasn’t good, and the things that have followed from it are even worse...

Those who have seen Gore Verbinski’s The Ring will probably experience more deja vu than anything else while watching Nakata’s earlier version, at least the first time around. There are a number of important differences— especially when it comes to technical matters, such as the way in which the two movies deploy their respective soundtracks— but the American version changed very little that didn’t need to be changed as a consequence of the shift in setting. Most of the major points of distinction between Verbinski’s version and Nakata’s seem to stem from the perception— which is probably correct— that American audiences require more in the way of explanation than their Japanese counterparts, and are less willing to accept at face value that which is outside their own experience. Certainly the first thing that struck me, as an American, about Ring was its blasé acceptance of the reality of psychic powers. Ring features no fewer than four characters with some degree of paranormal mental talent, encompassing everything from Yoichi’s limited ability to converse with the spirits of the dead to Sadako’s awesomely lethal psionic arsenal, and at no point is it suggested that there is anything at all odd about this state of affairs. Needless to say, any American screenwriter— at least any good one— would think twice before asking an audience to swallow that on top of a cursed videotape and an evil ghost. A lot of other things are glossed over in the Nakata-Takahashi Ring which a US filmmaker would instinctively want to explain, too— beginning with the title. (Although in that particular case, there’s a very good reason for the film’s reticence. In true Japanese style, Koji Suzuki admits to having chosen the title Ring simply by flipping through an English dictionary until he found a word that he liked.) The most jarring lacuna of all concerns the character of Sadako. Simply put, we never do learn who she really was, how she became what she is now, or what motivates her to do the things she does. This point honestly works both for and against Ring. On the one hand, it’s easy for me to imagine a person watching this movie all the way through to the end, and then yelling, “Yeah, but why?!” as the credits started to roll, and in any event, we are certainly denied the brief glimpse inside the character’s head that makes the American version’s Samara so frightening. Then again, refusing to explain her at all invests Sadako with the power to invoke a different kind of terror— the dread, not merely of the unknown, but of the unknowable. Like so many of the supernatural antagonists in Japanese movies, Sadako is as much a force of nature as anything else, a power before which the only chance for survival is submission. And the degree of submission Sadako demands is far greater than that which appeases Samara; I won’t say any more, except that those characters who survive their encounter with Sadako buy that survival at a much higher moral cost than is exacted from their counterparts in Verbinski’s The Ring, and this movie’s ending is all the more potent for it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact