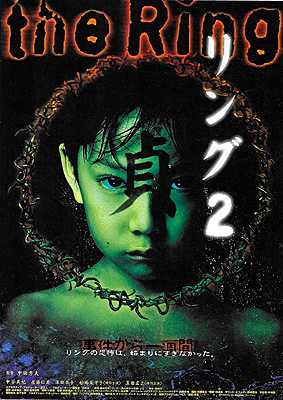

Ring 2 / Ringu 2 (1999/2005) ***

Ring 2 / Ringu 2 (1999/2005) ***

Hideo Nakata would like us all to know that he’s very sorry. Granted, it wasn’t his fault that Rasen, Joji Iida’s faithful-to-the-novel sequel to Nakata’s decidedly unfaithful adaptation of Ring, blew all kinds of sack, but this is Japan we’re talking about. People over there apologize for shit they had nothing to do with all the time. Fortunately for us, Nakata wasn’t content simply to apologize, either. Together with screenwriter Hiroshi Takahashi and the producers at Asmik Ace (the latter of whom were almost certainly the most culpable culprits in 1998’s Case of the Sucking Sequel), Nakata hoped to make restitution to his numerous and increasingly vocal fans by crafting a new Ring sequel— one that would begin by treating the ill-conceived Rasen (both the film and the novel) as though it had never existed. Author Koji Suzuki’s ever more ludicrous efforts to continue the Ring saga via one asinine science-fiction cliché after another would go into the dumpster where they had always belonged. And while one might question the wisdom behind some aspects of Ring 2’s alternate version of events after Reiko Asakawa discovered Ryuji Takayama’s body (Nakata himself admits that his and Takahashi’s primary inspiration was the universally reviled Exorcist II: The Heretic), this sequel at least gets a lot more right than Rasen had.

As if to assure us immediately that they understand exactly what had gone wrong the last time, Nakata and Takahashi start off not with any of Ring 2’s major human characters, but with Sadako herself. The bones which were so futilely retrieved from the bottom of that hidden well in Izu are now lying on a gurney in a police medical examiner’s laboratory, where they await identification by Takashi Yamamura (Yoichi Numata, of Hell and The Ceiling at Utsunomiya), Sadako’s last living relative. Yamamura’s reaction upon seeing the skeleton comes as something of a shock to Omuta (Kenjiro Ishimaru, from Kekko Kamen and The Discarnates), the detective who summoned him from his home on Oshima Island. The man seems frightened of the shrouded remains, and although he tells his hosts not to bother lifting the sheet, Yamamura declares that the bones from the well are unquestionably Sadako’s. He then storms out of the room with a command to burn the remains and “put the ashes wherever you like!” Presumably the old man’s hurry to be away stems from something he— but apparently not Omuta— sees for just a moment while staring at the gurney: a tendril of tangled, black hair snaking out toward him from under the sheet. Either way, Omuta informs Yamamura that no such immediate disposal of the body is possible, for there are curious circumstances surrounding it. One of the people who found the skeleton, mathematics professor Ryuji Takayama (Hiroyuki Sanada), died shortly thereafter, and the other, television journalist Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima), has disappeared. But perhaps even more troubling is the result of the coroner’s investigation. Though such a thing is surely biologically impossible, the condition of Sadako’s bones indicates that she died no more than two years ago, despite having lain at the bottom of the well more than fifteen times that long.

Meanwhile, Okazaki (Yûrei Yanagi, from Don’t Look Up and Ju-On: The Curse), a coworker of Asakawa’s, is faced with the task of hammering something usable out of the vanished reporter’s unfinished story about the legend of a cursed videotape that has recently begun circulating among teenagers all over Tokyo. One afternoon, he receives an unexpected visit from Mai Takano (Miki Nakatani once again), the student, assistant, and lover of Professor Takayama, who has come looking for Reiko. This gets Okazaki’s attention, for he has heard nothing from Asakawa in several days; policemen he expects to come sniffing around after missing people, but math department grad students are another matter. Mai explains her connection to Takayama, to whom Okazaki had not realized Reiko had once been married, and together they go to have a look at Asakawa’s apartment. There’s no one home, of course, but not a single one of the missing woman’s belongings— or her son’s, either— looks to have been packed. Asakawa did not disappear without leaving some evidence of her passing, however. The television set in her living room has been smashed to smithereens, and the melted remains of a VHS tape cling to the bottom of her bathtub. The phone rings while Mai and Okazaki are trying to make sense of the scene before them. It’s Omuta, hoping to reach Asakawa; her father has just been found dead in his home, his body in a frightful, unnatural state. He appears to have been preparing to copy a videotape shortly before his death.

It doesn’t take long for Omuta to trace the connection between Mai and Takayama, and he soon comes to discuss the case with her. Mai has very little light to shed on the mystery, of course. She has never heard of Sadako Yamamura, of her mother, Shizuko Yamamura (Masako), or of her presumed father, Dr. Heihachiro Ikuma (Daisuke Ban), nor does she have any idea why Takayama and Asakawa were digging for information about them. She has no clues to offer, either, about the similarities between the condition of Takayama’s body and that of Asakawa’s father. And she is totally in the dark regarding Asakawa’s apparent obsession with a mysterious videotape. All she knows— although she doesn’t say so in as many words to the detective— is that the web of half-glimpsed connections is beginning to scare the shit out of her.

Then come three breakthroughs in rapid succession. Mai spots Reiko and her son walking down the street while she peers out the window of an elevated train; Okazaki interviews a girl named Kanae Sawaguchi (Kyôko Fukuda), who claims to be able to get him a copy of the fabled cursed video; and a closer perusal of Asakawa’s story notes leads Okazaki to the mysterious fate of Tomoko, the teenaged niece whose sudden death made the legend of the curse a personal matter for Reiko. The latter discovery, in turn, brings to light the case of Masami Kurahashi (Hitomi Sato), the friend who was with Tomoko on the night of her death, and who has been confined ever since to the psychiatric ward of the hospital attached to Mai’s university. Masami is now practically catatonic, never speaking and expressing little in the way of thoughts or feelings except for an intense terror of the television set in the hospital’s dayroom. But the weirdest aspects of Masami’s story don’t come out until Mai and Okazaki meet with her psychiatrist, the rather eccentric Dr. Kawajiri (Fumiyo Kohinata, from Audition and Dark Water). Every attempt to take the girl’s mugshot for her case file resulted in a useless photograph, with Masami’s image overlain by a ghostly suggestion of a hooded man pointing at something out of the frame. Other images— most notably the kanji for “sada,” or “chaste”— appeared when Masami was later instructed simply to touch a cartridge of unexposed film. None of the characters recognize these images, naturally, but we in the audience know them as elements of Sadako’s deadly video. Then, after Mai walks out on the interview with Kawajiri, she witnesses a harrowing scene in the dayroom. The TV is turned on as a nurse leads Masami past on the way to the hospital’s veranda. No sooner does Masami come within sight of it than the innocuous program on the screen is replaced by the grainy image of a crumbling well in a stand of trees. A white-clad girl with knotted, black hair begins clambering out of the well, and all of the patients in the dayroom fly into hysterics. Then Mai touches Masami, and has her head invaded by the sight that drove the girl from sanity— the stringy-haired specter on the TV screen manifested in the real world, looming over Tomoko’s lifeless body. Masami pleads with Mai to help her after the contact is broken, but Mai has no idea how.

Reiko Asakawa might, though, so Mai returns to the search with renewed vigor. She gets a little assistance from the visions that start coming to her with steadily increasing frequency, and eventually runs into Yoichi Asakawa (Rikiya Otaka) at a train station. The kid’s alive, confirming that Reiko succeeded in lifting Sadako’s curse from him, but he isn’t a whole lot more communicative than Masami. Yoichi introduces Mai to his mother, sparking a strained sort of friendship between Takano and the two fugitives. Mai tells Reiko about her experiences during the past several days, and Asakawa begins to hope that Dr. Kawajiri’s studies of Masami Kurahashi might enable him to help Yoichi. Kawajiri does indeed have a plan, but when science is pitted against the supernatural in these movies, it generally doesn’t pay to bet too heavily on the men in the white coats. Meanwhile, Okazaki’s continued pursuit of the cursed video is going to get both him and Kanae into an immense amount of trouble.

If anything, Ring 2 is scarier than the first film in the series, but like many Japanese horror movies, it’s a little weak on narrative cohesion, and the ending makes no sense whatsoever. Even so, it came out far better than we have any right to expect from a movie whose creators were taking any cues at all from Exorcist II: The Heretic. This is especially so considering that what Nakata seems to have meant by following Exorcist II was this movie’s use of science as a weapon against occult forces— after all, the incontinent employment of bullshit science is precisely the thing that scuttled Rasen. What makes it work here is that Ring 2’s science is itself grounded in the occult in a very important sense. Western audiences may be forgiven for wondering what in the hell is going on when Dr. Kawajiri starts going off about dispelling Sadako’s psychic energy by channeling it into a body of water, but for those of us with some grounding in Japanese ghost lore, this is actually a pretty convincing way to attack the problem. The traditional form of ghost to which Sadako most closely corresponds is called a yurei. Yurei, from what I’ve read, are generally evil, nearly always female, and frequently deadlier than a boiler explosion in a razor blade factory. And more to the point for our present purposes, their genesis most commonly involves a wrongful death occurring in close proximity to water— a young girl getting bopped on the head and tossed down a well, for example. It doesn’t stretch the imagination much to hypothesize that the water acts as a sort of psychic solvent, absorbing the wrathful spirit of the deceased, and with that in mind, Kawajiri’s outwardly cracked scheme to use a swimming pool to siphon off Sadako’s psychic taint from her victims makes quite a lot of sense.

The issue of psychic taint exemplifies another thing that Ring 2 does beautifully right. Simply put, Hiroshi Takahashi clearly wrote this screenplay with the expectation that his audience would have seen Ring, and that the workings of the curse would no longer be a mystery for most of us. Recognizing that we already know who Sadako is and what she’s capable of, Takahashi begins the story by revealing that she is even more terrible than we had previously believed, the preternatural power of her mind so vast that she could survive for 30 years at the bottom of a sealed well, subsisting apparently on nothing more than the energy of her own hatred. When Omuta gives Yamamura the results of the coroner’s inquest, Nakata treats it like a scare scene— and by the gods, it is. The movie then goes on to show that everyone who has the slightest brush with Sadako’s curse— those whom it kills, whose spirits (with the curious exception of Ryuji Takayama’s) become enslaved to Sadako’s will; those who see the video and live to tell the tale; those who have not watched the tape for themselves, but are on the scene when somebody else’s seven-day deadline arrives; even those who so much as touch one of her other victims, assuming they’re sensitive enough— become polluted by that contact, with survivors of the video being the most deeply affected of all the living victims. Ring 2 runs with the original’s virus metaphor, but without literalizing it as Joji Iida (and Suzuki before him) had done so disastrously in Rasen. Here, it is Sadako’s lifeforce that is contagious, leaving a little piece of her power and consciousness behind in the minds and souls of everyone she touches. Many commentators come away from Ring 2 with the impression that Sadako seeks to reincarnate herself in Yoichi, but that strikes me as a mistaken interpretation. Rather, I believe Yoichi’s own psychic abilities simply make him a more effective conductor of the same spiritual current that afflicts so many of the other characters. Remember, just being in the room when Tomoko was killed was enough to make the previously normal Masami a walking relay station for Sadako’s killer broadcast. How much heavier an imprint must surviving the curse have left upon a child who was already capable of conversing with the dead? Meanwhile, Ring 2 shows us that Sadako does indeed possess all of the “normal” ghostly attributes, in addition to the more specialized characteristics familiar from the first film. An intensely eerie throwaway scene involving the clay reconstruction of the dead girl’s face which Omuta’s forensics men build up from Sadako’s skull establishes that there is a residue of will and power remaining in those bones from the bottom of the well, and that any scheme to neutralize the ghost’s deadly influence will have to come to grips with that power, too. Rather than rehash the mystery of Ring, or redefine it (as in Rasen), Ring 2 expands upon the answers we already have in a way that mostly remains true to the spirit of the first film. In that sense, it is an example of the rarest and best kind of sequel.

There’s one major respect, unfortunately, in which Ring 2 doesn’t shine quite so brightly. While it’s great to have Nakata and Takahashi back on the case, and while it’s even better to have Rie Inou— the One True Sadako— in action once again, the very fact of all that returning seems to have created a pressure to top Ring’s brilliantly unexpected and superbly executed conclusion, and the filmmakers’ efforts to do so fall far afield from success. Even after watching it three or four times in the space of as many days, I still have absolutely no idea what in the hell is supposed to be going on during this movie’s final fifteen minutes or so. Obviously Kawajiri’s Sadako extraction program doesn’t go exactly according to plan, and just as obviously there’s some manner of ghost-vs.-ghost aspect to the proceedings, but beyond that I seriously don’t have the first fucking clue. It’s a damn shame, too, because there’s a stretch of about 45 seconds buried somewhere in the muddle that might have given me nightmares if anything had actually come of it.

This review is part of what might be the most determinedly masochistic B-Masters Cabal roundtable in which I’ve yet participated, a loving (well, maybe not quite loving) look at the travestastic results which so often attend the film industry’s attempts to make lightning strike twice. Click on the banner below to see what horrors were suffered by the rest of the gang.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact