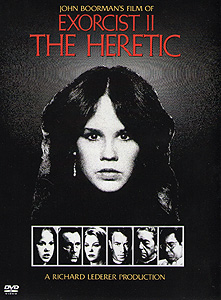

Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) -***˝

Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) -***˝

I was something like fourteen years old when I first learned of Exorcist II: The Heretic. I vividly recall the feeling of bewilderment that came over me when whatever I was watching previously ended, and the station broadcasting it announced that Exorcist II was next. I had already seen The Exorcist, of course, and I was aware by then of the movie’s reputation as a modern horror classic— an assessment with which I enthusiastically concurred. Most importantly, although I was by no means a cultural sophisticate at the age of fourteen, I had nevertheless caught on to the widespread perception that there was something vaguely seedy and disreputable about sequels, that they were normally frowned upon by exactly the sort of people whose opinions cause things to be regarded as classic. So the notion of an Exorcist II was a little mind-blowing, especially since I’d never heard of the movie before. Those of you who have seen The Heretic have doubtless already guessed that my mind was a good deal more blown by the time I had finished watching it.

As for the rest of you— well, it’s like this… Exorcist II: The Heretic isn’t just a bad sequel to a good movie. Hell, it isn’t even just a terrible sequel to a great movie. Rather, it is a film so comprehensively misbegotten, so determinedly wrong-headed, so utterly incapable of realizing its nonsensical and overweening ambitions that it has become a classic in its own right, albeit of an altogether different species from its predecessor. It is almost as if, instead of merely stealing and egregiously misapplying The Day the Earth Stood Still’s themes, Plan 9 from Outer Space had been made as an official sequel to it, with the full blessing and backing of the original producers. There’s one hugely important sense in which that analogy doesn’t hold up, however, for Exorcist II was not made by any late-70’s counterpart to Ed Wood Jr. No, the blame for this hypnotic fiasco rests with a well and for the most part justly respected director— no less a personage than John “Deliverance” Boorman! But what you have to remember about Boorman (and what Exorcist II’s producers clearly forgot) is that sometimes he’s John “Zardoz” Boorman instead. It was very definitely the latter avatar that arrived in Hollywood in the final quarter of 1975, bearing a cranium full of breathtakingly bad ideas.

This is not to say that all the bad ideas in Exorcist II came from Boorman or his rewriting partner, Rospo Pallenberg (officially credited as “creative associate”). By most accounts, there wasn’t much left of William Goodhart’s original script by the time Boorman and Pallenberg were through with it, but the sequel’s most basal betrayal of its predecessor appears to have been present in some form from the very beginning. That heretic referenced in the subtitle? He’s Father Lancaster Merrin (played in the various flashbacks by a returning Max Von Sydow). Apparently Merrin wasn’t just an old priest with a hard-on for archaeology, but rather a theological rabble-rouser who believed both that the power of Evil had grown so great that it now posed a genuine threat to God, and that the human race was beginning a new phase of evolution marked by the emergence of spiritual X-Men who could tilt the balance back toward the side of good. So basically, a strange hybrid of Zoroastrian, Manichean, and New Age Protestant mystic beliefs, which is nothing at all like Roman Catholicism. And of course, it’s also nothing at all like what we saw of Father Merrin the last time around. Anyway, now that Merrin is mysteriously dead after involving himself in the exorcism of Regan MacNeil (who’ll still be Linda Blair when we’re reintroduced to her in her high school’s auditorium), Cardinal Jaros of the Vatican (Paul Henreid, from Siren of Bagdad and Stolen Face) wants an investigation that might help defuse the increasingly disparaging rumors about Merrin. (“Many at the Theological College believe that he died at the hands of the Devil during that American exorcism. Some— and they are close to the Pontiff— go so far as to suggest that he was a Satanist at the end.” Right. Because the one thing follows so logically from the other…) To that end, Jaros summons Father Philip Lamont (Richard Burton, of Bluebeard and Doctor Faustus), who had once been among Merrin’s closest associates, from a failed exorcism of his own and dispatches him to New York, where Regan and her mother (who will not be appearing in this movie at all, Ellen Burstyn knowing a really shitty script when she sees one) now live.

As is only to be expected of a girl who was possessed by a demon once, Regan is just a little bit troubled these days, and her mom has her seeing Dr. Gene Tuskin (Louise Fletcher, from Mama Dracula and Strange Invaders), a psychiatrist specializing in juvenile patients. Regan claims to remember nothing substantial about that time when she was “sick,” but Tuskin is convinced that the memories are all in there somewhere— possibly even that Regan is just putting the doctor on about the amnesia so that she doesn’t have to talk about it. The first time Father Lamont barges into Tuskin’s office to discuss interviewing the girl about Father Merrin’s death, he interrupts Gene trying to sell Regan on a new therapeutic technique in which a machine she calls the Synchronizer puts both doctor and patient into the same hypnotic trance, allowing the former to experience directly whatever memories, ideas, or images the session dredges up out of the latter’s subconscious mind. Regan isn’t having it until Lamont shows up; paradoxically, the notion that people she’s never heard of want to know about the events she claims not to recall seems to make her more willing to get them out in the open. Then again, maybe it isn’t strictly Regan who changes her mind. Only Father Lamont has the necessary knowledge to interpret what happens next correctly, but the Synchronizer brings Tuskin face to face with the devil that once took up residence inside Regan, and it would seem that the otherworldly being still maintains a toehold in her psyche to this day. Tuskin starts fibrillating as soon as the Synchronizer brings her trance into harmony with Regan’s, and Lamont has to take Regan’s place to bring her back out again.

I’ll never get this synopsis written if I pause every time something monumentally stupid or misguided comes up, but let’s take a moment now to examine how abysmally foolish this scene is. It’s like a microcosm of the whole movie, so I think a digression is warranted. First off, have a look around Dr. Tuskin’s clinic. Notice that there isn’t one wall in the place that isn’t made of glass, and that apart from a few sliding doors which are tinted for no apparent reason, they’re all made of completely transparent glass, at that. This is supposed to be a psychiatric clinic for children, right? A place where trust is painstakingly built up, where dreadful memories are dragged into the light, where agonizing secrets and crippling insecurities are confessed, where infected psychic wounds are lanced and scrubbed out with psychoanalytic iodine? So doesn’t it seem to you like the first thing a patient there— to say nothing of a patient’s parents or guardians— would want is a little for-fuck’s-sake privacy?!?! Then there’s the Synchronizer itself. Most of what I’ve read about Exorcist II’s inglorious theatrical run has it that the first appearance of the Synchronizer was the moment when most audiences turned on the movie like kicked dogs, and no exceptional imagination is required to understand why. The fool contraption looks like something Wile E. Coyote would mail-order from the Acme Corporation as part of his latest scheme to catch the Road Runner, and it’s somehow all the worse for being small enough to fit in a desk drawer. This is SCIENCE!, people. Since we’ve already thrown practicality right out the window with the very set design, the Synchronizer ought to be big and impressive, and maybe even a little intimidating— especially given that Tuskin has to talk Regan into using it with her. As it is, Regan looks less afraid of what the Synchronizer might reveal than rightly contemptuous of the dinky and shoddily-built toy that her doctor has just produced from her desk. Now let’s consider Lamont’s role. Remember that Dr. Tuskin is having a life-threatening medical reaction to the effects of an experimental piece of psychotherapeutic hardware, and what’s more, a life-threatening medical reaction that shouldn’t even be physiologically possible. She’s in her own office at her own clinic, and her assistant, Liz (Belinda Beatty, of Deliverance), is standing right beside her when it happens. Does Liz summon the orderlies to assist her? No, she does not. Does she call 911 and get an ambulance rushed over at once from the nearest hospital? No, she doesn’t do that either. Instead, she turns over the reins of this catastrophically failing experiment to some schmuck off the street, who is avowedly here for no better reason than to interfere with a patient’s treatment, and whose intrusion is being temporarily suffered only because the patient seems to trust him for some unfathomable reason! The shared vision itself is an affront to The Exorcist’s memory, with Merrin squaring off against a possessed version of Regan who not only looks nothing like Linda Blair, but was plainly meant to double for her at her current age, rather than her age at the time of the possession incident. Possessed Regan also has a new and altogether less memorable voice, Mercedes McCambridge having been dumped ignominiously overboard in favor of one of Boorman’s daughters, doubled by Vladek Shaybal— whom some of you may remember as Mr. Boogalow in The Apple. I wish I could say the association was inappropriate in context. A jumbled and bewildering flurry of multiple exposures ensures both that the audience will have only the dimmest idea of what’s meant to be going on, and that whatever it is will look as naďve and tacky as possible. And if, after all that, the scene had somehow managed to retain one attenuated scrap of tension, mood, or even basic dignity, Boorman blows even it by having a couple of people wandering around in the background, rolling this… this… thing along with them. It’s large, it’s octagonal, it’s hollow in the middle, and it’s made out of some apparently squishy material encased in a cladding of gray or red plasti-leather (there must be at least two of the things— either that, or the cladding is interchangeable), and there is no way on God’s green Earth that anyone could pay attention to anything else so long as this inexplicable object is in the shot!

Anyway, Lamont does his damndest to sell Tuskin on his preferred version of events when she emerges from her trance safe and sound (no thanks to Liz). It’s far from clear at this point exactly what Tuskin believes to have happened to Regan back in Georgetown (and it will become not one whit clearer by the movie’s end), but the doctor certainly is not prepared to accept that an immortal being from Hell commandeered her patient’s body for a matter of weeks, and it’ll take a lot more than one visibly boozed-up blowhard priest to make her consider such a thing. That’s when Liz hands Lamont what we are told is a picture of him that Regan drew. The only indication that this is so is the white collar holding the figure’s black shirt closed at the throat. The head of the figure is surrounded by equally stylized flames, and the instant Lamont sees that, he goes on a lunatic rampage of rummaging, searching the clinic for a fire which he swears is present somewhere. He eventually finds it, smoldering in a box of oily rags and doll heads (!) in the basement, and we see at once why Lamont joined the priesthood rather than the fire department; banging on the box with a discarded crutch, he manages to expand a minor nuisance for the real firefighters into a blaze that bids fair to engulf the entire cellar, forcing the evacuation of the clinic. It’s okay, though, because in the midst of his manic flailing, Tuskin sees Lamont with his face ringed by flames in exactly the same way as in Regan’s drawing. So obviously, we must be dealing with the supernatural, right? And obviously, we must take Lamont at his awesomely over-delivered word that Tuskin’s machine “has proved conclusively that there’s an ancient demon locked within [Regan].” Tuskin, to the one bit of credit I’m willing to extend her, is not entirely convinced. She does, however, consent to a Synchronizer session between Lamont and Regan.

And what a Synchronizer session it is! Regan herself scarcely participates at all; her demon is running the show all the way. Now you may recall that The Exorcist never identified that demon by name, although the iconography associated with it was sufficient to tell someone with the correct background that Regan’s infernal tenant was the Babylonian archfiend Pazuzu. In retrospect, that was a smart move, for it turns out that Pazuzu is not a name that one can easily say with a straight face or hear without having to suppress a chuckle. Exorcist II, as in all things, is less circumspect, and when two of the principal players not only are called upon to invoke that name repeatedly, but also insist upon pronouncing it, “Pazuuuuuuuuzuuuuuuu,” you really can forget about any degree of seriousness surviving the utterance. Pazuzu shows Lamont how he was exorcized by Father Merrin from an Ethopian faith healer named Kokumo (played as a boy by Joey Green, and as an adult by James Earl Jones, of Conan the Barbarian and The UFO Incident). He hints vaguely but blatantly of a special relationship between him and the locust, about which the movie paradoxically makes an enormous deal while doing nothing of much substance with it. He confirms to Lamont that Regan remains under the shadow of his power despite Merrin’s best efforts, and asserts that he could reclaim Kokumo as well if he had a mind to— although it appears that that much at least is either a lie or an idle boast. Most significantly, Pazuzu reveals that Merrin, heretic or not, was right. Mankind has begun producing spiritual superheroes in response to the growing strength of cosmic evil, and Pazuzu’s activities on the Material Plane have been intended to destroy and/or corrupt these New Age saviors before they have a chance to fulfill their potential as agents of cosmic good. The vision Pazuzu grants Lamont under hypnosis suggests, however, that Kokumo has remained demon-free since his exorcism, which gives Lamont the idea that the former boy messiah might be able to guide him in completing Merrin’s unfinished work on Regan.

The bare fact that the whole second half of Exorcist II concerns a Catholic priest acting upon revelations from a pre-Christian Mesopotamian demon should be enough to tell you that this movie takes place in an entirely different moral and metaphysical universe from The Exorcist. Simply put, this is what you get when you hand over the reins of a sequel to somebody who openly detested the original film. To all appearances, Boorman deliberately did the opposite of everything that had worked in The Exorcist, or that would have made sense as a continuation of its story. Father Merrin, the Van Helsing of the previous movie, was originally the perfect embodiment of the Roman Catholic Church as believers would like to conceive it, a wise yet humble representative of a stern yet benevolent authoritarianism. Boorman, having none of that, recasts him as an institutionally embarrassing rebel, a man who discovered and proclaimed a secret truth despite all the obscurantist obstruction that his bosses could throw his way. Regan MacNeil was originally a collateral casualty of the struggle between Good and Evil, a bystander whose innocence was itself the point. Pazuzu picked her precisely because there was nothing special or important about her; his true target was always the faith of Regan’s would-be rescuers, and the injustice of his attack on her was itself his strongest weapon against that faith. Again, Boorman has other ideas, and we are now asked to believe that Regan is Jean Gray for Jesus, with Merrin (or Lamont) and Pazuzu squabbling over her allegiance like Professor X and Magneto. Most galling to any thoughtful fan of The Exorcist, however, is what Boorman has done with Damien Karas. Karas, after all, was the real hero of The Exorcist, and his eventual victory over Pazuzu was the most stridently and specifically Christian thing about it. It was not strength that defeated Evil in the end, but literally Christ-like sacrifice, as Karas surrendered his own life— and, if you’re a pre-Vatican II Catholic, his own soul— to lure the demon out of Regan. There was no way to tell the story that Boorman wanted to while acknowledging that turn of events, so I guess we shouldn’t be too surprised that Exorcist II ignores Karas completely, refusing even to mention his name. Absolutely the only recognition Karas receives in the sequel comes by implication, as one of the oft-mentioned three deaths that occurred at the MacNeil house four years ago. To be fair, there probably is a compelling and thought-provoking movie to be made on the premise of Exorcist II— it just wouldn’t be a sequel to The Exorcist, and Boorman’s determination to make it one reveals his contempt not only for the earlier film, but for that movie’s fans as well.

Of course, there’s a lot more wrong with Exorcist II: The Heretic than its glaring inappropriateness as a sequel to The Exorcist. This movie may not reach quite the same dizzying heights of utter madness, but it surely does feature much the same combination of interesting but plainly incomplete ideas, overblown and inescapably absurd production design, theoretically impressive but totally inapt casting, and unabashedly headache-inducing dialogue that had characterized Zardoz three years earlier. In fact, it’s hard to talk coherently about what went wrong with this movie on a technical level, simply because virtually everything went wrong with it. I guess we’ll start with subplots blowing up on the launch pad. I didn’t mention this stuff in my synopsis, because I was too busy trying to hold onto the main narrative through-line, but Ma MacNeil’s old sidekick, Sharon (a returning Kitty Winn), is the closest thing Regan has to an onscreen mother-figure this time around, and she winds up the central player in a truly nonsensical attempt to bookend the film with Lamont’s failed attempts to rescue young women from demonic visitations. We’re meant to interpret it as a thematic echo, I think, but it doesn’t work because Boorman, Pallenberg, and Goodhart between them never saw fit to establish a common theme between the two incidents. Hell, there’s no visible reason why Pazuzu should take a last-minute interest in Sharon at all! Similarly, Exorcist II is at its Zardoziest when Lamont finally succeeds in tracking down Kokumo. The first half of their meeting plays out like some bullshit hippy vision quest, with Kokumo ensconced in the basement of a mud house at the center of some ancient city in the Armpit of Africa, dolled up in a hilariously ill-advised locust-shaman costume that makes him look like he’s on his way to a casting call for Kaiju Big Battel. Then, with literally zero transition, and literally zero effort expended to make rational sense of what’s happening, the scene shifts to a thoroughly modern entomological laboratory, where a nattily-dressed Kokumo is revealed to be the head of a project to breed a strain of locust in which the young females— pay attention now, son… that there’s what we call a metaphor— have been divested of the “evil” swarming instinct. The trouble here is that the whole subplot is nothing but a metaphor. The main plot would have arrived at exactly the same place, in exactly the same way, without it.

Now let’s talk production design. I’ve already discussed Tuskin’s lab at length, so I won’t go into it again here. The MacNeils’ penthouse apartment commits most of the same sins, in the sense that nobody would ever in a million years live there— not least because the city building inspector wouldn’t let them. Forget the hideous mirrored dovecote on the rooftop terrace, a veritable Studio 54 for pigeons. Forget the floor-to-ceiling windows serving as the outer walls in the bedroom of an underage girl. The apartment’s most mind-blowing feature is the railings around the aforementioned terrace, which are broken every four feet or so by gaps fully wide enough for a mature adult to fall through unimpeded! And then Boorman calls the maximum possible attention to this “outrageously dangerous” (to quote second assistant director Victor Hsu) arrangement by staging a scene in which a partially re-possessed Regan comes within an ace of sleepwalking right through one of those gaps! At the other end of the spectrum is the set for the village where Kokumo lived as a boy. One of the lesser crewmembers commented at the time that the village set was so realistic that entering it ought to require a passport, and maybe it really was that impressive in person. On film, though, it looks about as convincing as the tiki bar village in Queen of the Amazons, a vivid illustration of why nobody was filming exteriors on a soundstage anymore by the late 1970’s.

Casting and dialogue here are difficult to separate from each other, because their respective failures are mutually reinforcing. Max Von Sydow, inevitably, shows everyone how it’s done in his handful of scenes, undaunted and unbowed by the absurdity of what Boorman has asked of him. Nobody else— not even poor James Earl Jones— can make any comparable claim. It comes as a tremendous shock to hear that Richard Burton was generally sober for the first few weeks of production, because every second of his performance simply bellows “liquor-soaked ham.” It’s a performance that The Tempter or Holocaust 2000 would be proud to call their own. Louise Fletcher as Dr. Tuskin takes the opposite tack, displaying such a pronounced lack of affect throughout that it’s tempting to imagine Tuskin driven to raiding the medicine cabinet at her clinic by the pressures of her job, especially after Lamont thunders in with his declarations about Evil and demonic possession. Linda Blair comes off by far the worst, however. Never an actress of range or delicacy, and visibly struggling with the insecurity that comes of inexperience, Blair is just no match for the part of a teenager who unexpectedly learns that she’s destined for greatness as one of God’s shock troopers, and she isn’t helped at all by Boorman’s inexplicable conviction that the perfect metaphor for her emergence as an ethereal being was a goddamned high school tapdance recital. Chances are nobody could have made the role work, and Blair never had a hope in Hell.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact