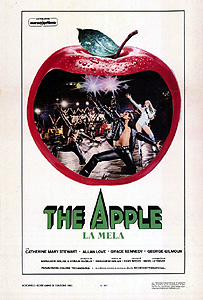

The Apple/Star Rock (1980) -***

The Apple/Star Rock (1980) -***

Let me try to set the stage for you. It’s about two hours into B-Fest 2005, and a reliable old standby, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, has ceded the screen to something called The Apple. I and about 250 other seriously committed movie freaks have just endured two or three massively kitsch-ridden musical numbers in rapid succession, and we’re at the point where it seems like whatever story this film possesses is about to get rolling at last. The hero and heroine are standing in the main villain’s office, being tempted with promises of fame and riches beyond their wildest imaginings, and all of a sudden, the scene is rudely interrupted by yet another musical interlude, this one set in the bowels of Hell, with all the principal characters now obviously tricked out as various figures from the Bible. Hero and heroine are Adam and Eve, complete with scandalously skimpy costumes made out of strings of fake foliage, while the Big Bad has donned a Dracula cape and sprouted one (just one, mind you) little gold horn from the left side of his forehead. The more conventionally attractive of the villain’s two primary male minions, meanwhile, is now parading around in a gold lamé g-string, attempting (in song, of course) to convince the heroine to take a bite from the comically immense plastic apple he holds before her. And as if that weren’t enough, all the legions of the netherworld— demons, vampires, zombies, and Beelzebub alone knows what else— soon get into the act, forming a sort of ragged and irregular chorus line surrounding the main action. It was during this demented spectacle that I first leaned back in my seat and asked myself, “My God— what the fuck am I watching here?” It would not be the last time that question rose up to torment me.

With a bit of distance now between me and the experience of having The Apple sprung on me effectively without warning (by which I mean that though I was indeed warned, nothing anyone could say will really prepare you for watching this film), I can now give something of an answer to my oft-repeated query. The Apple is Yoram Globus and Menahem Golan’s lunatic attempt to film a biblical allegory combining Genesis and Revelation in a paranoid sci-fi context, and to do it in the form of an extravagant disco musical. It’s even dumber and exponentially more bizarre than that sounds, too. Made in that brief period during which the 1970’s were over but didn’t yet realize it, The Apple can be seen as the culmination of the trend that produced such brain-damagingly terrible musicals as Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Xanadu, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Like them, it fuses the traditional Broadway sensibility with contemporary pop music to create a succession of auditory monstrosities which together suggest that the last living descendant of Victor Frankenstein forsook medicine at some point to pursue a career in show business instead. But, as is only appropriate considering its futuristic setting, this movie also looks ahead to musical forms that were just beginning to make their presence felt in 1980; though the main filter through which The Apple’s show tunes are squeezed is definitely the then-fading disco genre, the practiced ear (and the practiced eye as well) will detect hints of the burgeoning new wave and cock rock movements in most of the big production numbers. And apparently on the theory that this movie’s agenda wasn’t already sufficiently overloaded by its top-heavy spectacle and excessively earnest spiritual concerns, The Apple also takes a page from the Phantom of the Paradise playbook by positing that the modern-day music industry is ultimately controlled by Satan himself, and then causes all sorts of rhetorical problems for itself by making the good guys a bunch of dirty hippies— the very people who invented selling out as we know it when their subculture achieved critical mass and the record label A&R men came knocking on their doors with contracts in one hand and cocaine in the other.

We begin with the 1994 World Music Festival, a gala event organized under the auspices of a gigantic record label called Boogalow International Music. The eponymous Mr. Boogalow (Vladek Sheybal) is up in the control room of the arena in which the festival is held, watching the show along with his smarmy black sidekick, Shake (Ray Schell). The act onstage at the moment is the duo of Dandi (Alan Love) and Pandi (Grace Kennedy), evidently proteges of Shake’s, and he and the boss are using all manner of advanced biofeedback gizmos to measure the audience’s reaction to the show. Needless to say, the crowd’s vital signs are running high— as I’d certainly want them to be if I had been the one forking over the cash to pay for all those dancers and all those lighting rig operators and all those outrageous Cirque-du-Soleil-by-way-of-an-Italian-Road-Warrior-rip-off costumes. But Shake’s elation at his vicarious success is disrupted when the next performers take the stage and get an even more favorable reaction. In fact, the success of dueting folkies Alphie (George Gilmour) and Bibi (Catharine Mary Stewart, from Night of the Comet and World Gone Wild) throws Shake and Boogalow alike for a loop, since it is widely accepted as an article of pop-culture faith that both love songs and folk music are hopelessly passé— and just to complicate matters further, Alphie and Bibi aren’t signed to BIM, but have rather come all the way from Moosejaw, Saskatchewan, on their own as free agents. Boogalow is forced to resort to some soundboard trickery to sabotage the interlopers’ performance and make sure that his people walk away with whatever prizes the music festival awards.

Nevertheless, Mr. Boogalow did not get to be where he is by ignoring up and coming talent; he just likes to be certain said talent comes up on his terms. To that end, he has Shake invite the kids from Moosejaw to the after-show party at his place, where he tries to convince them to sign a recording contract with BIM. Bibi likes the idea, at least enough to give it a try; perhaps Dandi’s bid to seduce her at the party tipped the scales for her. Alphie is less accommodating, however. He rightly believes that Boogalow will try to find some way to screw them, and he wants nothing to do with BIM unless and until he and Bibi can scrape together enough money to hire a lawyer. Bibi prevails, however, and thus it is that the two of them find themselves in Boogalow’s office, falling headlong into a musical number set in Hell. Alphie takes that unexpected development as a sign from on high, but evidently it was just a hallucination on his part, and he is unable to convince Bibi that Boogalow is really Satan, and that by signing his recording contract, Bibi will in fact be signing away her soul. Bibi goes her own way, and soon finds herself with a completely reinvented identity, a pair of burly, tusk-toothed bodyguards named Bulldog (Derek Deadman, of Jabberwocky and Time Bandits) and Fatdog (Günther Notthoff, from Hot and Sexy and The Corpse in the Thames), and a pimped-out limo which we’re not supposed to notice is really just a 1970 Impala station wagon with lots of “futuristic” widgets welded to it. While Alphie sulks in his rented apartment, writing unsalable songs about romantic betrayal, Bibi rises to the summit of stardom, taking Pandi’s place both in the BIM marketing offensive and in Dandi’s heart.

Some time passes. It isn’t really clear how much, but I’m guessing it’s supposed to be several years, on the grounds that at least that much time would have to pass to account for the societal transformations that greet us with the next change of scene. Boogalow is no longer just a slimy music impresario, and BIM is no longer just the world’s biggest record label. Rather, Boogalow International Music has somehow expanded to supplant the government of at least the United States, if not the entire world, and its head now rules as a rather eccentric authoritarian dictator. Everyone under his power is required at all times to wear one of the iridescent, triangular “BIM” stickers which Boogalow’s marketing chief devised as a promotional gimmick back in 1994. (Mark of the Beast, anyone?) Each day, early in the afternoon, the entire population must drop whatever they were doing and perform a bizarre dance routine to the tune of some awful song by a musician from the old BIM stable— it’s supposed to be a national fitness program, but really it’s just an excuse for another hideous musical number. And of perhaps the greatest importance (polemically speaking, anyway), debauchery, bad behavior, and overall soullessness are encouraged throughout the land with all the force of law. Ever since that day when Bibi signed her BIM contract, Alphie has spent his time in between show stoppers pining uselessly for her and getting himself beaten up by her bodyguards while trying to get close to her outside of various concert halls. He may not seem like much of a threat, but he makes such a pest of himself that Boogalow eventually decides that it might be worth his while to try corrupting the boy again. With that in mind, he arranges for Alphie to be admitted to BIM headquarters, and then unleashes Pandi in an effort to make the boy forget all about Bibi. When even that fails (I don’t think I’d be very keen on the experience if the girl I was in bed with insisted on performing a musical number while she was fucking me, either, no matter how much drugged liquor I had in me), Boogalow brings out the heavy artillery, and rigs it so that Alphie stumbles upon the room in which Bibi lies in bed with Dandi. So distraught is Alphie that he immediately runs off and joins a hippie commune.

Even Boogalow’s wizardry has its limits, though, and one of the things he is too weak to overcome is (sigh…) the Power of Love. When Pandi figures out that Bibi, despite everything, is still in love with Alphie, she has an inexplicable change of heart, and helps the girl escape from Boogalow’s clutches. Alphie is already gone from his old apartment by that point, of course, but his ex-landlady (Miriam Margoyles, from The Awakening and End of Days) gives Bibi some tips as to where he might have run off to. Bibi meets up with the leader of the hippies (Joss Ackland, of The House that Dripped Blood and Citizen X) after a short search, and he leads her to the commune, where she is reunited with her former boyfriend and makes the significantly symbolic gesture of peeling the BIM sticker off of her forehead. It takes Boogalow another couple of years to track Bibi down (by which point she and Alphie have had a child and forsaken completely any recognized principles of personal hygiene), and when he and his followers come to collect Bibi, it sparks the final contest between Boogalow and Mr. Topps (also Joss Ackland), the divine figure who arrives on the scene in a flying, gold Bentley to lead the people of the commune up into heaven. That’s right, folks— it’s the Hippy Rapture! And just like the fundamentalist wacko Rapture, I’m thinking I’d have a much better time if I got lumped in with all the infidels and sinners being left behind…

I fear I’ve done a really lousy job of describing The Apple. So far afield is it from any conventional notion of moviemaking that even the best written recap will doubtless leave the reader imagining something far more sedate than what actually appears on the screen. The rational mind refuses to accept that a movie like this one could be made by anybody but the likes of Ray Dennis Steckler or Ted V. Mikels, so the knowledge that it was written, produced, and directed by the usually fairly straitlaced (if also exuberantly trashy) Golan and Globus tends to make one ratchet back one’s vision of The Apple’s madness. Rest assured, however, that this movie is about as bent as any in the annals of history.

That very point raises a fascinating question. While there are indeed a few filmmakers out there who routinely create movies with every bit as high a “what the fuck?!” factor as The Apple, Golan and Globus are absolutely not among them. Say what you want about the output of their Cannon Group over the course of the ensuing decade, but in the final assessment, movies like Missing in Action and Death Wish 3 were remorselessly commercial in both conception and execution. There is nothing commercial about The Apple, however— nothing at all. It’s the kind of film you expect from a maverick auteur, not the masterminds behind the most successful independent Hollywood studio of the 1980’s. At the time The Apple hit the theaters, disco was already entering its death throes; hippies were culturally irrelevant throwbacks who had more in common with Cheech and Chong than with the pop messiahs of the late 1960’s; New Age religiosity was on the wane, retreating before the rising tide of evangelical Protestantism. In short, this was a movie with no natural audience, which tied into no major trend except the tentative resurgence of the musical, and which seems calculated to alienate anyone who would have gone to see it when it was first released— after all, the disco fans who could be expected to appreciate the bulk of the innumerable musical numbers might well take exception to being told that they were really the Devil’s dupes, while the last straggling hippies who might appreciate The Apple’s affirmation of their ghettoized and moribund counterculture would surely never go to see a disco musical in the first place! What in the hell could Golan and Globus have been thinking?

Before I take my leave of The Apple, I would like to offer a suggestion to anyone reading this who now feels motivated to see it for themselves. While I enjoyed The Apple infinitely more than I was expecting to, I think it well within the realm of possibility that my reaction was strongly colored by the context in which I saw it. I was at B-Fest, in the company of hundreds of my tribesmen, and it was early enough in the program that enthusiasm throughout the crowd was running very, very high. Had I watched it by myself at home, however, it seems very likely that I would have found The Apple a soul-scorching ordeal. Consequently, I advise that this movie be watched only in relatively large groups. Get all your friends together. Order a couple of pizzas. Crack open a twelve-pack and pass around a big-ass bottle of high-octane whiskey. And whatever you do, don’t press “play” until you’re all feeling pleasantly nuts. Trust me on this, folks— I’m a professional.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact