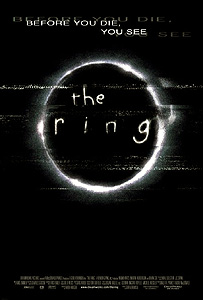

The Ring (2002) ****

The Ring (2002) ****

Right off the bat, let me point out that Iím doing this backwards. I have this neurosis, see, which generally prevents me from watchingó let alone reviewingó sequels to or remakes of movies I havenít yet seen, especially when I know I could, without too much effort, get my hands on the original. But I really did want to see The Ring, and because thereís just no substitute for watching a movie in the theater while youíve got the chance, and because my copy of Hideo Nakataís Ring/Ringu isnít going to get here for at least three or four weeks, I forced myself to overcome that neurosis and see the remake first. As a consequence, thereís going to be very little of the compare-and-contrast approach I usually take when reviewing remakes, in that all I know about the Japanese Ring is what Iíve gleaned from reviews Iíve read and stills Iíve seen. Also, before I really get started talking about this surprisingly impressive film, Iíd like to explain why its existence in the first place makes me paradoxically mad. Now if youíre a b-movie/ horror movie geek of any magnitude, it would be virtually impossible for you to have made it to the last quarter of 2002 in total ignorance of Nakataís Ring. Itís been literally years since I saw a movie generate so much word-of-mouth buzz, and if we limit the field of consideration to foreign films, Iím not sure Iíve ever seen such a thing. So it was heartening to hear last year that Dreamworks had acquired the US rights to Ringó even if the movie was only going to be released direct-to-video in an incompetently dubbed, pan-and-scan print, at least Iíd get to see the thing in a language I understand without having to find a PAL-compatible, region-free DVD player. (If an English-subtitled, NTSC-format, VHS edition of Ring existed a year ago, nobody told me about it.) And besides, there was at least a small chance that the American edition would be respectfully handled, and the all-too-brief appearance of Godzilla 2000 on the big screen meant that it wasnít completely ridiculous to hope that Ring would play in theaters too. But having bought the US rights to a foreign horror film whose reputation was more than strong enough to put a respectable pile of money into the Dreamworks corporate bank account, what did the studio heads do? They hired a bunch of Americans to put together a fucking remake, thatís what! As if US audiences were no more sophisticated now than they were in 1956, and wouldnít be able to deal with a movie that featured no white faces in the cast! Now I suppose itís possible (now that The Ring seems to have proven itself at the box office) that Dreamworks will yet have the class to give the original some kind of legit distributionó I hope thatís the case, but I canít say Iíd be willing to bet on it. So even though the Americanized version of The Ring turns out to be a vastly better film than I would ever have dared expect, the mere fact that it got made leaves me with a sneaking feeling that Iím being condescended to.

The story follows fairly closely what Iíve been able to piece together of Ringís, though it appears to have been streamlined considerably. It begins with a pair of teenage girls named Katie (Amber Tamblyn) and Becca (Rachael Bella) watching TV together in the former girlís room, trading paranoid stories while channel surfing a startlingly immense television set. (You know, I wonder if the little plaid skirts the girls are wearing are meant as a Western translation of the distinctive Japanese schoolgirl uniform beloved by pederastic perverts the world over...) Becca cuts off Katieís increasingly muddled rant about the baleful effects the electromagnetic waves from all the TVís and cell phones and radios in the world are supposedly having on our central nervous systems to ask if her friend has ever heard the story about the cursed videotape. Apparently, thereís this tape floating around which contains nothing but a series of nightmarish abstract images, and the moment you get finished watching it, the phone rings and a voice on the other end of the line tells you youíre going to die in a week. This story creeps Katie out because, or so she claims, she and three of her friends had exactly that experience on vacation recentlyó a week ago to the day, in fact. And though the succession of scare setups that follows for the next few minutes each turn out to be false, we see just how real the curse of the tape is the moment the two girls separate to prepare for bed. Becca finds Katie slumped over in the linen closet, and it isnít a pretty sight.

Three days later, Katieís aunt, journalist Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts, from Tank Girl and Children of the Corn IV: The Gathering), comes to pick her son, Aidan (David Dorfman), up from school. Aidanís teacher wants to talk to Rachel about how the boy is dealing with his cousinís inexplicable death (he and Katie were evidently quite close); in particular, she is troubled by some of the drawings Aidan has been turning in for art class. Each drawing depicts a girló apparently Katieó in a black dress, and though itís sometimes a bit difficult to be sure (seven-year-olds donít usually have much grasp of perspective after all), that girl always seems to be shown buried beneath the ground. The pictures seem normal enough to Rachel at first, but things start to look a little bit different when the teacher mentions that the earliest of them pre-dates Katieís death by fully a week. This wonít be the last display of paranormal talent weíll see from the boyó and yes, this will be important later.

The next scene has Rachel and Aidan attending Katieís funeral, and it is here that the reporter first gets drawn into the sinister web surrounding the mysterious videotape. Rachelís sister (Lindsay Frost, of Monolith) seems to be taking her daughterís death better than her husband is, but she is still troubled by the seeming impossibility of it all. Who the hell ever heard of a sixteen-year-old girlís heart just stopping for no reason? None of the doctors sheís talked to can give her a satisfactory explanation, and she seems to think that Katieís friends may know some important detail that they are loath to divulge for fear of getting themselves into trouble. Recognizing Rachelís skill at getting people to talk when they donít necessarily want to, her sister asks her to see if she can figure out what the other kids are hiding. A bit later, Rachel gets herself in good with Katieís friends to a sufficient extent that they (somewhat reluctantly) tell her about the video she and her friends watched when they were away at the cabin on Shelter Mountain. They also tell her that Becca was checked into a mental hospital the day after Katie died, and that all three of the friends with whom Katie went on vacation a week before are dead now, too.

Obviously, a story as strange as that is going to set off Rachelís reporterís instincts, and despite its patent absurdity, she begins looking for evidence that there might be some kind of truth to it. She finds plenty. First of all, her research reveals that the three friends with whom Katie went on that vacation to Shelter Mountain are indeed dead, and that they all died at 10:00 pmó the same time as Katie herself. Second, though Rachel doesnít initially understand the importance of this (she certainly will in a couple of days), the dead kidsí faces are all strangely distorted in photos they took on the last day of their trip. Finally, when Rachel goes to Shelter Mountain herself and stays the night in the same cabin as Katie and her friends, she finds an odd, unmarked videotape on the rack in the rental office, which she watches that night on the theory that it might be the one the kids supposedly watched. Man, thatís one creepy video. Interspersed between images of rotting horse carcasses, huge centipedes, people slithering through mud, and the like are more prosaic visions that somehow seem no less menacing: the reflection of a severe-looking woman combing her hair in an oval mirror, a man pointing to something while standing in an attic window, random landscape shots that nevertheless seem to depict the same basic place, a tree that seems to be on fire. But the defining image on the tape is that which both begins and ends it, a ring of light on an oddly rough and scabrous background. Then the very moment Rachel hits the rewind button on the cabinís VCR, the telephone rings, just as Beccaís urban legend said it would. And when Rachel answers it, the voice of a little girl hisses ďSeven daysĒ and the line goes dead. Starting to believe in curses now, arenít you, Rachel?

So assuming she really is cursed, the best move for Rachel would probably be to see if the video holds any clues that might help her get un-cursed. And if video analysis is what she needs, then the natural person for her to turn to is her ex-husband (or maybe just ex-boyfriend) and Aidanís absentee father, Noah (Martin Henderson), who just happens to be some sort of video technician. Of course, if Noah is going to be of any help, heíll have to watch the tape, too, thereby incurring the curse himself; this doesnít seem to dawn on Rachel until sheís actually talking to her ex, by which point itís much too late to think of a way to spare him the danger. Sure enough, the phone rings right after Noah finishes watching, though Rachel insists on letting the answering machine pick it up. (At the end of the scene, she deletes the message without even listening to itó itís often little touches like that that turn a good movie into a great one.) Then, just in case our heroes donít have enough going on to provide them with a sense of urgency, Rachel accidentally leaves the copy of the tape she makes on Noahís equipment where Aidan can find it. The boy acquires a curse of his own during a bout of insomnia a day or two later.

The clues Rachel gleans from the videotape lead her and Noah hip-deep into what really is one of the more convincingly multi-layered mysteries Iíve seen in a horror film of recent provenance. As the details pile up, it becomes increasingly clear that everything revolves around a little girl named Samara (Daveigh Chase, who, when she finally shows up onscreen, gives one of the most frightening performances by a child actor Iíve ever seen), whose short life was filled to overflowing with the strange and unexplained from one end to the other. Having concluded that the video is not so much cursed as it is haunted by Samaraís unquiet spirit, Rachel proceeds on the assumption that everything would be okay again if somebody could just figure out what it is the dead girl needs to enjoy a peaceful afterlife. Of course, by the time she gets that idea in her head, itís already day number seven, and some ghosts arenít nearly as communicative as the ones in The Sixth Sense.

Itís obvious that the makers of The Ring have a profound understanding of how modern horror movies work, and itís equally clear that they figured we do, too. Right from the beginning, the movie plays sneaky games with audience expectations, meeting and confounding them in roughly equal measure. My favorite trick among those used by director Gore Verbinski might best be called the bait-and-switch scare setup. Anybody likely to be watching The Ring has already seen scads of horror films, and is intimately familiar with what the setup for a scare looks like. Not only that, most of us can usually tell from the way a given setup is built exactly what kind of a scare a movie has in store for us. Again and again throughout The Ring, Verbinski plays on that knowledge to misdirect us. He shows us, for example, a close-up on a characterís face with a darkened hallway visible over her shoulder, and we immediately know to brace ourselves for something to attack out of that darkness. Then Verbinski holds the setup long enough for us to question our initial assessment, and sucker-punches with a totally different kind of scare the moment our guard is down. Itís an unexpectedly canny approach, and a brilliantly effective one.

A bag of tricks with more inside it than the usual Hollywood ďBoogaboogaĒ isnít the only reason The Ring is such a pleasant surprise, either. You might expect the US version of a film whose story is set in motion by the fate of a bunch of doomed teenagers to make those doomed teenagers its exclusive or near-exclusive focus, but thatís not at all what happens here. Though itís true that Rachel and Noah are pretty young, theyíre still very much adults, and the concerns that motivate them are adult concernsó none more so than Rachelís agonized awareness that sheís fighting for her sonís life as much as for hers. Perhaps even more surprising is the degree of success the cast attains in pulling these deeper, more complicated characters off. I tell you, itís been so long since Iíve seen an American horror movie with adult protagonists get released that Iíd begun to think the folks in charge of the industry had forgotten that people over the age of eighteen even watch the things! And in keeping with its more mature characters, the movie also takes a more mature approach to its subject matter, leaving an array of unexplained, half-explained, and hinted-at story elements wide enough to give a screenwriter of the currently dominant explain-it-Ďtil-it-drops-dead school a heart attack. (Although I should probably point out here that Iíve been told this version offers concrete explanations for plenty of things that the Japanese were content to leave ambiguous.) Though I dearly hope Dreamworks wonít succumb to the Ring-sequel plague that has gripped Japan for the last four years, at least there are enough unexplored corners of the story that a halfway decent sequel neednít be out of the question. All in all, we gaijin lucked out on this remake to such an extent that it scarcely seems possible.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact