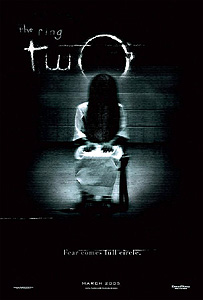

The Ring Two (2005) -*

The Ring Two (2005) -*

Like a lot of filmmakers who first make their mark by scaring the crap out of people, Hideo Nakata never wanted to be a “horror director.” But when somebody makes a horror film as compelling as Nakata’s Ring, the public— to say nothing of the movie-industry power-brokers— are invariably disinclined to let them forget it, a truth which is just as inescapable in Japan as it is in Hollywood. Nakata then further cemented his genre typecasting by stepping in after the debacle of Joji Iida’s Rasen to salvage what was by then a franchise, rebooting the sequel continuity with the far more effective Ring 2. But although he sat out Ring 0: Birthday to pursue projects of a different sort, audiences and producers alike knew what they wanted from Nakata, and in 2003, he found himself back in the bogeyman business helming Dark Water, adapted from yet another story by Ring creator Koji Suzuki. Nakata tried again to break away from horror the following year, this time taking the drastic step of relocating to America. This gambit was not exactly a resounding success. The first project to which the director was attached on this side of the Pacific was True Believers, a story about a couple with fertility troubles, whose efforts to conceive a child end up embroiling them with the activities of an evil cult. Not an auspicious second start for a man who was looking to leave horror behind him, but Nakata could at least console himself with the knowledge that True Believers had nothing whatsoever to do with stringy-haired ghost girls, right? Even that small comfort was soon to be denied him, however, because the bosses at Dimension Films began having second, third, and fourth thoughts about the screenplay, and True Believers became mired in Development Hell. (It’s still there, incidentally, with no plans for release until at least 2009.) That’s when Nakata got the call from Dreamworks SKG— would he, by any chance, be interested in directing a sequel to the American version of The Ring?

That sequel was itself in some trouble at the time, perhaps not in Development Hell, but certainly in Development Purgatory. Gore Verbinski, who had directed The Ring, had no intention of doing another such film. Noam Murro, the director of television commercials who was the producers’ first choice to replace Verbinski, came down with a bad case of “creative differences,” and took his leave of the project in March of 2004— which cut things rather close for a movie that was slated for release in November. Star Naomi Watts was due on the set of Peter Jackson’s King Kong at the beginning of the following year, lending a further sense of urgency to the search for a new director. Richard Kelly, who wrote and directed Donnie Darko and was the next name down on the producers’ short list, didn’t want the job any more than did Gore Verbinski. And if the patchwork of visibly unrelated ideas in the finished film is any indication, the script was something of a shambles. Yet for some reason, Nakata accepted the studio’s invitation to revisit a franchise which he had crossed the world’s broadest ocean to escape. If, again, we may judge from what wound up on the screen in March of 2005, that reason was most likely an irate phone call from Nakata’s landlord.

It would seem that the videotaped curse of Samara Morgan has been spreading rapidly since Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts) passed it along to save the life of her son, Aidan (David Dorfman). When a high school senior named Jake (Ryan Merriman, from Final Destination 3 and Halloween: Resurrection) invites his date, Emily (Emily Van Camp), back to his home in the small, out-of-the-way town of Astoria, Oregon, telling her that he’s got something he wants to show her, we know immediately what the boy is talking about. Emily, evidently not a fan of horror movies, is reluctant to watch what Jake describes to her as the scariest video he’s ever seen, but she relents when the boy’s invitation to do so crescendos into a disturbingly strident demand. While Emily cues up the tape, Jake leaves the room and places a call to another boy named Eddie, the preceding link in the curse’s chain. There are tantalizing indications that both kids understood fully the ramifications of watching Samara’s video when Eddie passed it along, but that plot thread is cut short by Emily’s cowardice— she plays the tape as per instructions, but instead of watching it, she merely sits on the sofa in front of the TV set with her eyes closed and her hands over her face. Jake had been a scant two minutes from his deadline when Emily pressed “play” on the VCR, and Emily gets to witness something a hell of a lot more frightening than the horror film she thought she was avoiding when Samara (played this time by Kelly Stables, who had apparently been Daveigh Chase’s stunt double in The Ring) comes calling to collect her due.

By a remarkable coincidence (and don’t we all just love those?), Astoria, Oregon, happens to be the very town to which Rachel and Aidan moved in order to restart their lives in a setting uncontaminated by unpleasant Samara-related memories. Rachel now works for the Daily Astorian, the dismal local rag owned and edited by Max Rourke (Simon Baker, from Red Planet and Land of the Dead), meaning that she is among the first to hear about Jake’s death and Emily’s descent into catatonia. She recognizes the symptoms, of course. Courting the wrath of Astoria’s answer to Barney Fife, Rachel manages to drag out of the girl the present location of the videotape, then takes advantage of small-town laxness in the field of home security to snag it from Jake’s living room. Then she burns the tape in a trash can at the park— as if that’s going to accomplish the slightest bit of good this late in the day.

Aidan, meanwhile, starts having nightmares. Yes, they’re about Samara; no, Aidan doesn’t tell his mom about their content even after she catches him having them; and yes, the previously tack-sharp Rachel now proves too dense to make the connection on her own until nearly a third of the way through the movie, despite the fact that she’s having similar dreams herself. And evidently Samara has seen Freddy’s Revenge as well as the original A Nightmare on Elm Street, because it swiftly becomes abundantly clear to everybody but the protagonists that her aim this time around is to secure a second chance at material life by hitching a ride in Aidan’s body. Why him? Why now? Why period? Who the fuck knows— and honestly, who really cares at this point? I mean, it’s not like that’s the most illogical thing to happen in The Ring Two, anyway. Not by a long shot. To paraphrase the mad scientist from a certain Al Adamson movie, when a villain who formerly dealt in videotaped curses turns instead to calling down ambush attacks by herds of identical computer-animated deer, there can be no intelligible explanation for anything.

This is the movie I was afraid of back in 2002, when I first heard that Dreamworks were going to remake Ring instead of just distributing the original in an English-language version. To anyone who thought Gore Verbinski’s The Ring was a shameful bastardization of Nakata’s masterwork, I refer you to the sequel for a remedial education in what shameful bastardization really looks like. Imagine Ring reinterpreted as an Italian Exorcist rip-off, as A Nightmare on Elm Street 9: The Dream Outsourcing, as Poltergeist 4: Even Tom Skerritt Said No to This One. That is the true measure of the travesty that is The Ring Two. Any semblance of narrative or dramatic integrity packs its bags and takes a room at the nearest flophouse as writer Ehren Kruger pushes a bunch of randomly selected horror cliches into a pile in the corner and calls it a screenplay— ignoring, while he’s at, it a couple of interesting ideas which he has incorporated seemingly by complete accident. Maybe you’ll sit up and take notice when Dr. Emma Temple (Elizabeth Perkins) shows up to inaugurate the subplot in which Max— Rachel’s love interest by that point in the film— apparently sics the local child welfare outfit on Keller out of concern that Aidan’s possession symptoms are in fact the effects of neglect or abuse. Well too bad. That rather startling concession to a reality which so frequently gets ignored in horror movies fades out almost immediately, its place taken by Rachel’s hackneyed efforts to discover the identity of Samara’s biological parents, a plot-thread which ultimately gives us both a tale-telling nun (as in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors) and an appearance by a gone-to-seed Sissy Spacek— Carrie herself, for the love of Baal!— as the long-dead psionic’s predictably insane mom. Or perhaps what catches your eye will be that all too rapidly disposed-of business about Jake and Eddie in the prologue. The DVD edition of The Ring Two includes a short film called Rings, which posits the existence of a thrill-seeking subculture of teenagers who deliberately risk death at Samara’s hands, and reveals that both Jake and Eddie were caught up in this suicidal culture of curse-courting. Watch it and marvel at the filmmakers’ obtuseness in failing to recognize a superior premise for a sequel even as they held it in their hands.

Faced with such a script, it comes as no surprise that Hideo Nakata’s direction is almost totally devoid of the astute and judicious touch he brought to Ring and Ring 2. Only two scenes present any evidence that he cared in the slightest about anything to do with this movie save the accompanying paycheck. The first of these orphaned bright spots comes when Jake’s seven days elapse; Nakata unexpectedly shows the ghost girl’s emergence from the television from approximately Samara’s perspective, putting a novel spin on an image that was in danger of losing its potency due to overexposure. The second comes at the climax, which essentially reprises the heroine’s climb up the well— with the specter in hot pursuit— that had figured in the conclusion of Ring 2. That momentarily chilling scene blew up on the launch pad the first time around, but Nakata comes closer to doing it justice here. On the whole, however, the main distinction that Nakata earns from The Ring Two is the dubious one of having directed a Ring sequel even worse than Rasen.

This review is part of what might be the most determinedly masochistic B-Masters Cabal roundtable in which I’ve yet participated, a loving (well, maybe not quite loving) look at the travestastic results which so often attend the film industry’s attempts to make lightning strike twice. Click on the banner below to see what horrors were suffered by the rest of the gang.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact