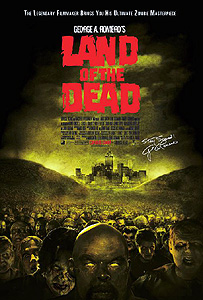

Land of the Dead (2005) ***˝

Land of the Dead (2005) ***˝

Sometimes there’s an advantage to being one of the last people on Earth to see a movie which was already up to its armpits in buzz before it even started shooting. Although it’s often quite a challenge to avoid learning more than you want to know about plot points, the ambient chatter can sometimes cause you to focus your attention on those aspects of the film which have attracted the most interest and controversy among the fans, and make you give them more serious thought than you might have had you seen the movie completely cold. In the case of Land of the Dead, I was indeed mostly successful in maintaining a mental quarantine against plot information, but I had heard quite a bit of interesting stuff about the film nevertheless. I knew, for instance, that Romero had taken the idea of a domesticated zombie which had figured in Day of the Dead, and extrapolated it into the possibility of the zombies learning new information, rather than just retrieving dormant memories from their former lives, and I knew that that angle on the story didn’t sit well with a substantial fraction of the audience. I knew that Romero, in keeping with the current state of the zombie-movie art, had framed Land of the Dead less as a horror movie per se than as an action film with horrific elements, and that lots of his old fans were pissed off about that, too. I had heard something about a piece of heavy anti-zombie hardware with the annoyingly cutesy name “Dead Reckoning,” and was sufficiently clued in at that point to be pleased that the producers decided at the last minute not to name the movie after the thing, as was the plan for a while there. And of course, I had heard that Romero was up to his old social commentary tricks again, and had used the opportunity presented by Land of the Dead to take a few swipes at, among other things, the neurotic security state which American politicians have been patiently assembling ever since a bunch of God-huffing lunatics decided that the surest way to get into heaven was to fly other people’s airplanes into world-famous office buildings. All these things I thought about as I watched the long-delayed fourth installment in Romero’s genre-defining zombie saga, but what I found I kept fixating on was a point for which nothing I had heard or read had prepared me. Nobody said anything about Land of the Dead being the next best thing to a big-budget Italian Road Warrior rip-off with zombies!

Considering that this is a sequel to a set of movies the most recent of which was released fully twenty years ago, it seems only fair to expect a certain amount of recap. A garbled montage of film and audio clips efficiently establishes that something has caused the dead to rise all over the world as mindless, flesh-eating monsters. The living dead multiplied with nightmarish speed, as each person the zombies killed returned to life themselves, until finally, an unspecified length of time after the initial resurrection, there are only scattered pockets of humanity left on Earth. One such pocket is in Pittsburgh, where the triangular peninsula defined by the intersection of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers creates a sort of natural stronghold against the undead; the zombies don’t swim, and with all the bridges blocked or blown up, it’s a relatively simple matter to stop them from marching downtown. Just string up a solidly framed electrified fence, and even the zombies will get the picture eventually. And by no coincidence at all, the man who devised this sensible scheme happens to have been the real estate mogul responsible for the luxury condo tower, Fiddler’s Green, which stands near the apex of the triangle, overlooking the junction of the two rivers. Civilization may be collapsing all around him, but Kaufmann (Dennis Hopper, from Waterworld and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2) will be goddamned if he lets that have any negative impact on his property values!

Of course, cities are not known for producing much in the way of such important things as food or medicine or the raw materials for even the lightest industry, and so somebody is going to have to leave the safety of Kaufmann’s fortified triangle on a regular basis in order to raid the depopulated settlements of the hinterland for supplies. Naturally, the privileged inhabitants of Fiddler’s Green itself are far above such hazards, and Kaufmann’s private army has much more important things to do with its time. Thus it is that the job falls to a band of civilian mercenaries under the leadership of engineer Riley Tenbo (Simon Baker, from Red Planet and The Ring Two), paid and provisioned by the master of Fiddler’s Green. Why put your freelance shitkickers under the leadership of an engineer, you ask? The reason is quite sensible, actually— Riley’s last big job in his original field of expertise was designing and overseeing the construction of Dead Reckoning, a high-tech armored fighting vehicle which rather resembles Damnation Alley’s Landmasters scaled up from a Winnebago’s proportions to those of an eighteen-wheeler. Kaufmann, as you might imagine, footed the bill for its creation. It is this machine which largely accounts for the success of the scavenging raids, and it seems only fair that the man responsible for its existence should get to command it in the field. As it happens, Riley is leading his last raid before retiring from the mercenary business on the night when we meet him, but he is visibly concerned about what will become of the team when his successor-apparent, Cholo (John Leguizamo, of Spawn and the Assault on Precinct 13 remake), takes over. Cholo is both extremely reckless and obviously in it for nobody but himself, as he amply demonstrates when he manages to get a member of his sub-team killed while looting a liquor store for booze to sell on the black market. (Actually, “gray market” might be the better term. We’ll be seeing later on that Kaufmann’s police don’t much care what goes on at ground level, provided it involves neither the zombies infiltrating the perimeter nor the rabble infiltrating Fiddler’s Green.) In the long run, however, the death of Cholo’s man will be overshadowed in importance by the fallout from the evening’s zombie massacre. As usual, the undead fall by the truckload beneath Dead Reckoning’s machine guns and autocannons, but one of the zombies (TekWar’s Eugene Clark) has a most extraordinary reaction to the carnage. From the way the huge black zombie carries on, you’d think he were taking the second deaths of his fellows personally— and as we shall see, there is every reason to believe that he is. What’s more, there is also every reason to believe that this particular zombie, despite his shambling gait and inability to speak, isn’t a whole lot dumber than the average live human.

But let’s leave that aside for the moment and join Riley and Cholo as they separately discover just what a shameless, conniving bastard Kaufmann really is. Riley tenders his resignation and then heads off with his horribly scarred halfwit friend, Charlie (Robert Joy, from Amityville 3-D and The Dark Half), to begin Getting On With His Life. In Riley’s case, Getting On With His Life means going to see a man called Brubaker (Alan Van Sprang) to close a deal on a car which he plans to drive up north to the Canadian wilderness, on the theory that the countryside offers the best bet for sustainable human life in the face of the zombie menace. But when Riley arrives at Brubaker’s garage, he discovers that Kaufmann has paid off a midget gangster named Chihuahua (Phil Fondacaro, from Troll and Bordello of Blood) to offer the salesman a better price for the vehicle, and there’s nothing but an empty space in the clutter of the shop to prove to Riley that the car was ever there in the first place— apparently the boss man has some reason for wanting to make sure Riley stays conveniently at hand. Furious, Riley seeks out Chihuahua at a nightclub he apparently owns; Charlie comes along, too, as the two men have a years-long history of watching each other’s backs when danger is afoot. They arrive just in time to see some of Chihuahua’s goons toss a young woman (Asia Argento, of Trauma and Demons 2) into a cage with two zombies, giving the louts in the crowd something new and exciting to bet on. It’s disgusting, and Riley was already in a bad enough mood to begin with. He pulls his gun and starts doling out the whoop-ass, joined in short order by Charlie, who turns out to be an extraordinary marksman for a man with only one working eye. Between the two of them, they kill Chihuahua, rescue the girl in the zombie cage, and empty out the bar more or less completely. Then the cops come, and it’s “Go directly to jail; do not pass ‘Go,’ do not collect $200” for Riley, Charlie, and Slack (the zombie-cage girl).

Cholo, meanwhile, is learning some lessons of his own. He has no intention of spending the rest of his life on Pittsburgh’s ground floor, leading the Dead Reckoning crew into ass-risking action night after night after night. No, he plans on moving up in the world, and he has a couple of bargaining chips which he thinks he can parley into a condo in Fiddler’s Green. First of all, there’s his years of loyal service to Kaufmann, over the course of which he has smuggled a hell of a lot of stuff that strayed far from the “necessities and staples” that are the Dead Reckoning missions’ nominal objective. But more importantly, Cholo knows that the truckloads of trash which Dead Reckoning also escorts out of the city frequently contain the dead bodies of Kaufmann’s enemies— particularly enemies with ties to the various dissident movements which crop up on the streets of Pittsburgh from time to time. If Kaufmann won’t honor the claims of loyalty, Cholo imagines, then maybe he’ll bow to blackmail instead. Let’s just say that for a mercenary shitheel, Cholo is one naďve little twinkee. There is no bond of mutual obligation strong enough to make Kaufmann open the hallowed doors of Fiddler’s Green to a cholo like Cholo, and as for blackmail, that’s what Kaufmann retains a staff of goons for.

Even so, the old bastard has more on his hands than he bargained for, and on three separate fronts, at that. As soon as Cholo leaves Kaufmann’s Fiddler’s Green office and fights his way past the thug who was supposed to make him disappear on his way to the lobby, he calls up his pals, Foxy (Saw II’s Tony Nappo), Mouse (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), and Pretty Boy (Joanne Boland— like the Cryptkeeper used to say, irony is good for your blood), with a plan to get even. Cholo and his friends are going to steal Dead Reckoning, and use its firepower to hold all of Fiddler’s Green hostage! Kaufmann takes just as hard a line against bargaining with terrorists— even terrorists whom he had been happy to use for years before stabbing them in the back— as a certain American president, however, and his answer to Cholo’s ingenious scheme is to spring Riley from his jail and send him to get Dead Reckoning back. Riley’s price for performing this service is the release of both Charlie and Slack, whom he then takes along with him on his mission. The catch, naturally, is that Riley really intends to keep Dead Reckoning for himself, and drive it on up to Canada in place of the car Kaufmann bought out from under him— and not even Motown (Krista Bridges), Manolete (Sasha Roiz), and Pillsbury (Pedro Miguel Arce), the three soldiers Kaufmann has saddled him with, are going to stand in his way. Of course, that intelligent zombie and the army he’s been raising outside of Kaufmann’s perimeter look like they’re packing enough monkey wrenches to derail all three of Kaufmann’s, Cholo’s, and Riley’s competing schemes.

As was the case with all of Romero’s previous zombie movies, the zombies themselves are a background presence throughout most of Land of the Dead, which is mostly concerned with the question of how humanity address the problems the living dead present. But unlike its three predecessors, Land of the Dead deals with the undead as an endemic, rather than epidemic, threat. Despite the dire picture painted by Day of the Dead, the human race has indeed survived the coming of the zombies, and has shifted its footing in precisely the direction implied by Dr. Logan’s research in the earlier film. The question now is how to live with the zombies, not how to eradicate them. In making this switch, Romero does an unexpected thing, and apparently draws upon one of the best of his imitators in envisioning a more or less stable post-zombie order. A number of the ideas here had surfaced previously in a late-80’s comic book called Deadworld, which took Romero’s zombie trilogy (as it could still be called in those days) as its primary inspiration. The practice of looting for sustenance in little towns with relatively small zombie populations; the catastrophic slumification and gangsterization of those human settlements that do manage to hold a defensive position against the undead; hell, even the idea of betting on orchestrated clashes between humans and zombies as a form of underworld entertainment— all of these things showed up in Deadworld at one time or another. Fortunately, Romero isn’t just ripping off people who had already done the same to him. Deadworld was (at first, anyway) a very well thought-out handling of the gut-munching zombie premise, and did a hell of a lot more than rip off Romero’s living dead movies. Similarly, Romero doesn’t so much copy Deadworld in Land of the Dead as open a dialogue with it. In the same way that Deadworld writers Stuart Kerr and Vince Locke extrapolated from the movies into situations which Romero seemed not to have considered, Land of the Dead builds on what it borrows from Kerr and Locke. “Sure,” it seems to say, “of course gangsters and thugs and criminals would survive a zombie uprising in disproportionate numbers— people like that spend their whole lives facing life-threatening danger anyway, so they’re pretty well prepared. But what about the super, super-rich? A lot of those people got where they are by being every bit as merciless as any crack-ghetto warlord. If a few of them could move fast enough to secure a city and keep some kind of economy going so that their money didn’t instantly become worthless, they’d be in a position to impose what amounts to a new form of feudalism, wouldn’t they?” In many ways, I find this vision of Z-Day + x Years far more satisfying than the one implied by Day of the Dead. It recognizes the almost limitless resourcefulness of human beings, along with their almost limitless capacity for seeking advantage at each other’s expense. Despite the way things looked from the depths of the 80’s, when Romero’s zombies were last heard from, even the most apocalyptic disaster would not truly have been the end of the human story, but merely the beginning of a new and probably uglier chapter. And that is exactly what Romero gives us here.

Startlingly enough, Romero’s most valuable asset in refocusing the zombie saga on the issue of old battles being re-fought on new terms is Dennis Hopper’s performance in the role of Kaufmann. You might expect Hopper of all people to ham up a storm, playing the part as the apotheosis of every moustache-twirling capitalist black-hat who ever appeared on a movie screen, but that’s not at all what he does. Instead— and you’ll never believe this without seeing it for yourself— he holds back to such an extent that any actor who lacked Hopper’s natural intensity would have lapsed into forgettable blandness. By turning down the volume this way, Hopper turns Kaufmann into what may be the most believable Evil Capitalist yet seen— a genteel yet authoritative exterior underlain by the steel of utter ruthlessness.

There was one conspicuous crib from Deadworld which I left out of that list two paragraphs ago— the idea of an intelligent zombie who leads his mindless fellows in concerted, organized attacks upon the living. Now, it would have been difficult to fit a fully intelligent ghoul like Deadworld’s King Zombie into the framework of the Romero movies, and Land of the Dead’s “Big Daddy” is nowhere near that bright. However, there is a noticeable difference between him and Bub, the partially domesticated zombie in Day of the Dead, in that no systematic conditioning is necessary to make Big Daddy regain some semblance of his prior humanity. This is shaping up to be the most controversial aspect of Land of the Dead, and as usual, I find myself sort of caught in the middle of the argument. On the one hand, there’s something intriguing about the notion that in all the panic over the dead rising from their graves with murder on what little remained of their minds, we might have missed the point that at least a few of the zombies retained abnormally large measures of both intelligence and emotional capacity. On the other, I still say Romero’s biggest mistake in Dawn of the Dead was trying to make the zombies sympathetic, and Big Daddy is the most conspicuous sympathy grab for the living dead to date. Most notably, never once do we see him eating a person, although he does kill plenty of them. While I can see how there’s room for some semi-intelligent, semi-sentient zombies in Romero’s mythos, the way Big Daddy is portrayed downplays his essential zombieness in a manner that is damaging to the film as a whole. Even Bub ate people, after all! There are also times when Big Daddy seems a little too smart, and has a little too much success in passing on his discoveries to the rest of the zombie horde. Take, for example, the scenes which show him or one of his followers successfully (if also clumsily) wielding an M-16 or a Steyr AUG— two of the most inaccurate, jam-prone, and breakable automatic rifles in service anywhere. I could have bought Big Daddy with an AK-47 (if it’s simple enough and sturdy enough for the Russian infantry, it’s probably simple enough and sturdy enough for a zombie, too), but a Steyr AUG is really pushing it. All told, I suppose I have to call it a draw on the subject of Big Daddy; he’s an interesting idea, but rather poorly handled.

In the end, though, the greatest strength of Land of the Dead, the thing that enables it to rise in victory (if not exactly triumph) over even its most serious shortcomings, is that it shows that it is indeed possible to make an action-oriented zombie film that is neither a totally hollow waste of time nor simply an extended exercise in abject idiocy. Admittedly, calling Land of the Dead the best zombie action movie yet released doesn’t sound like much when the principal competition is offered by Resident Evil and House of the Dead, but the point is that this film is nothing at all like either of those. As I said before, what it reminds me of most is a better, smarter, more competently staged version of all those post-apocalypse movies the Italians made to cash in on the success of The Road Warrior. Seriously, the bulk of the characters here could have walked right out of an Enzo G. Castellari movie (in fact, I think it’s sort of a shame that Romero didn’t save a place for Castellari mainstay Fred Williamson in Land of the Dead’s cast), and what is Dead Reckoning, really, if not a non-pathetic update of Warrior of the Lost World’s Megaweapon? Indeed, it might have helped the movie a bit if the design department had allowed Dead Reckoning to have a little more in common with Megaweapon— as it is, the machine is awfully cool, but looks terribly out of place as the only purpose-designed futuristic fighting vehicle in a fleet otherwise made up of converted motorcycles and station wagons. I kept expecting Dead Reckoning to transform into God Jinrai, and leave its crew to their own devices while it went off to pick a fight with Deathsaurus and Leokaiser. But that aside, Romero has definitely discovered the secret to a believable mix of zombies and whoop-ass, and that secret appears to be the scrupulous avoidance of both self-consciously artful fight choreography and flashy digital stunt trickery. The action in Land of the Dead is without exception of the low-down and dirty variety that we saw so much of in the post-apocalypse films of the 80’s, and handling it that way makes the movie seem ever so much more serious than its recent competitors by narrowing the gap between the way things work in the fictional world of the story and the way they work in our own. In Land of the Dead, we only have to accept the existence of flesh-eating zombies. We don’t have to buy into all-powerful corporations wielding magical technology, 30-year-old ravers who turn out to be expert gunslingers, or Milla Jovovich as a kung fu-fighting SWAT team badass, and without those additional demands on audience credulity, Land of the Dead is able to focus the viewer’s attention on what’s really important. I’d like to think today’s filmmakers will take notice and learn from Romero’s example, but somehow that doesn’t seem terribly likely.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact