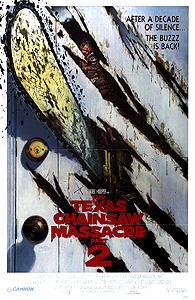

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) *

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) *

I probably shouldn’t have such a hard time believing that Tobe Hooper directed The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. No matter how brilliant the original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was, Hooper’s subsequent career demonstrates pretty conclusively that his stunning breakthrough film was mostly a fluke. It isn’t that Hooper hasn’t made anything else of merit— he also has Salem’s Lot and Poltergeist to his credit, and one of these days, I’m going to offer up a defense of Lifeforce that will surely have everyone who hasn’t done so already questioning my sanity— but most of his movies have been pretty limp affairs overall. Still, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is more than just pretty limp. It’s a travesty to equal all but the very worst Friday the 13th sequels, its level of quality far closer to that of Nail Gun Massacre than to what was attained by its illustrious predecessor. And what may be a harsher condemnation still, it is exactly what you would expect from producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, whose Cannon Group bought the sequel rights when Bryanston Pictures, which had distributed the original, went down in flames as collateral damage in the prosecution of its mafia backers.

That’s right, folks— Golan and Globus. The same jackasses who gave us all those horrendous ninja movies in the 80’s, the guys who footed the bill for Chuck Norris’s blossoming into the cartoon character he is today, the men about whom the best thing we can say with a straight face is that they were just about the last distributors to show any interest in English-language versions of movies by the likes of Luigi Cozzi and Ruggero Deodato when the Great Italian Rip-Off Machine was beginning to wind down. That’s whose bright idea it was to make a sequel to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a full twelve years after its initial release, by which point the American slasher movie had long since entered the decadent phase of its history. By 1986, all but the most stubborn had given up trying to make a serious film in the genre without some admixture of the supernatural, and since Hooper’s original premise left precious little room for ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night, screenwriter L. M. Kit Carson took the other popular approach of the era, and rendered the sequel as a black comedy. In fact, I get the distinct impression, watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, that Carson was taking his stylistic cues from Frank Henenlotter’s Basket Case; there are any number of situations in this movie that would fit more comfortably into a Henenlotter picture than anywhere else. Such a plan might even have worked were it not for two things. First, Kit Carson’s writing lacks the effortless lunacy that makes Henenlotter’s work so funny, and second, Tobe Hooper can’t direct comedy to save his dick. So rather than using the change of focus to bring any genuine wit or legitimate originality to the proceedings, Hooper and Carson instead made a film that alternates between inexpertly playing reprisals of the previous installment’s major set-pieces for laughs and ill-advisedly copying the earlier Motel Hell’s treatment of essentially the same material.

An opening crawl tells us— in contradiction to what was implied in the first film’s intro— that the family of deranged cannibals who tortured Sally Hardesty and killed her friends and brother back in 1973 were never caught. In fact, when the police in Muerto County, Texas, went to investigate Sally’s story, they couldn’t even find the house where she said the killers lived, and the case was closed for lack of evidence— “officially, the Texas Chainsaw Massacre never happened.” Remind me never to turn to the cops for anything next time I find myself in Muerto County, alright?

Nevertheless, even fourteen years after the Hardesty girl’s ordeal, the occasional rumor of a chainsaw killing arises somewhere in Texas. And then, one evening in the summer of 1987, some hard evidence surfaces at last, and in a most unusual manner. Somewhere in the Dallas area, you see, is the headquarters of a radio station with the somewhat counterintuitive call-sign KOKLA. One of KOKLA’s most popular DJs is a woman who calls herself Stretch (the closing credits say her real name is Vantia Brock, but you’d never figure that out from the rest of the movie), whose show format is one of those mixtures of fundamentally incompatible genres that no real-world DJ would ever concoct. Stretch (Caroline Williams, from Stepfather II and Leprechaun 3) also takes a hell of a lot of requests, and on that fateful day, she finds herself plagued by repeated calls from a couple of assholes driving cross-country with a car-phone and a revolver. What makes these tools ten times the nuisance they would be ordinarily is that the call-in feed through the soundboard to Stretch’s headset is configured in such a way that neither she nor her engineer, L.G. McPeters (Lou Perry, of Poltergeist and The Cellar), is able to hang up on them, and they insist on tying up the station’s phone line for minutes at a time. As it happens, that means Stretch and L.G. get to hear the whole sorry episode when the Moron Twins decide to play chicken with the wrong pickup truck, and wind up on the receiving end of a chainsaw attack. And because KOKLA station policy requires that all incoming calls be recorded, Stretch winds up with several solid minutes of screams, gunshots, and buzzing power tools on tape.

Now, before we go on with the show, I think I should discuss this first murder scene in some depth, because it really shows off how the carefully crafted intensity of the original has been forsaken in favor of crass slasher stupidity of the “Hey! Wouldn’t it be so cool if we…” variety— this despite the fact that, structurally speaking, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 isn’t really a slasher movie at all. After being run off the road by the Moron Twins earlier in the day, the drivers of a big, blue pickup with tinted windows somehow divine which way the offending travelers are going, and then somehow manage to make up for a considerable head-start to position themselves for an ambush on an otherwise deserted bridge several hours later and what must be close to 200 miles away. The killers force the Moron Twins to stop their car, and then engage them in a high-speed chase, remaining neck-and-neck with their car despite the fact that the truck is going in reverse. We will later learn that the police estimate the Moron Twins’ speed at the time their car finally crashed (damned hard to drive with your head sawn off, you know) at 90 miles per hour, which makes the entire situation even more patently impossible than it seems on its face— reverse is the lowest gear in any automotive transmission, and there isn’t a vehicle on the road that could go even half that fast backing up! As for why the truck gives chase in reverse, it’s so that Leatherface (now played by Bill Johnson, who also turned up with bit-parts in Confessions of a Serial Killer and Future Kill) can stand up in the bed and take the Moron Twins’ car apart with his saw— all while simultaneously wielding a partially preserved corpse as a sort of macabre muppet. It’s retarded, and it gets worse the more time you spend thinking about it. It also sets the tone for the entire movie.

The next day, the police cleanup crew is intruded upon by a cop from another jurisdiction who goes by the name of Lefty Enright (Dennis Hopper, whose appearance here seems surprising at first, until you remember that he was also in Queen of Blood and Night Tide). Enright is pretty much the most despised lawman in Texas these days, for he has spent the last fourteen years obsessing over the officially mythical chainsaw murder clan. He’s got a personal interest in the case, you see— he’s Sally Hardesty’s uncle. Well, despite the runaround he gets from the local authorities, Enright makes such a pest of himself that he gets his quixotic quest mentioned (albeit in an extremely snide and dismissive tone) in one of the Dallas newspapers, and thereby comes to Stretch’s attention. Stretch seeks Enright out to play him the tape of the overheard murder (which the police, incidentally, claim was nothing but a grisly but routine traffic accident). He doesn’t initially take her any more seriously than his fellow policemen took him— who can say why?— but a day or so later, he rethinks his position, and talks Stretch into playing the tape on the air, ostensibly to raise community awareness or some such horseshit.

Meanwhile, the movie is about to get even dumber. Apparently Stretch and L.G. double as KOKLA’s roving news crew, because the two of them are soon putting in an appearance to document the outcome of a state-wide chili cook-off that’s held every year in Dallas. For the second year running, the winner of this contest is one Drayton Sawyer. And would you look at that— he’s Leatherface’s dad! (Jim Siedow, returning from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.) I guess we know what the secret ingredient is, don’t we? But on the way home from his latest triumph, Drayton gets a call on the car-phone from his sons, who have just heard themselves on the radio, courtesy of Stretch’s broadcast of the murder tape. Dad issues orders for the boys to stop by the station and clean up the mess they made. After all, think what it would do to the family business if word got out that the most beloved catered chili in Texas was made from human flesh!

You’ll notice I said “sons.” Plural. Sure, Leatherface’s— sorry, Bubba Sawyer’s— little brother got flattened by an eighteen wheeler last time around, but how could we have a Texas Chainsaw Massacre movie with no villains but Bubba and his pa? With that in mind, Carson has conveniently invented a replacement for the dead Sawyer boy, in the form of older brother Paul (Bill Moseley, from Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out and the 1990 remake of Night of the Living Dead). Paul Sawyer (you’ll need sharp ears to catch his name on the two occasions when anybody mentions it, so it’s no wonder just about everybody who sees this movie refers to him by the nickname “Choptop”) is a Vietnam vet who came home from the war with a steel plate in his skull and a brain even more scrambled than it had been to begin with. Of all the Sawyers we’ve met so far, Paul is definitely the craziest. He’s also the one who makes the first impression when he and Leatherface show up at KOKLA to kill Stretch and L.G. After making his intentions known, Paul goes after L.G. with a claw hammer while Bubba takes on Stretch in the studio. Bubba, however, doesn’t really feel like killing his prey; no, he’s gone and fallen in love with her instead. Consequently, he leaves her alive to take the fight to the family a scene or two later, at the labyrinthine underground lair they’ve converted from an amusement park that looks like it was converted in turn from some sort of mine. Meanwhile, Lefty Enright shows up too, armed with no fewer than three chainsaws of his own. What? You thought maybe he’d just use his police-issue sidearm and riot gun? Where’s the fun in that?!

Okay. You want to know what a bad idea looks like? How about this: You make a horror movie so ground-breaking and powerful that for decades to come, even people who would never consider seeing it are at least dimly familiar with its basic contours. Six years later, somebody else comes along and makes a black comedy premised on the same setup. Six years after that, you go and make a sequel to your film, ripping off in the process the movie that parodied you. That’s what Tobe Hooper and Kit Carson did with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Motel Hell already covered every inch of this territory, from the cannibalism-as-family-business angle to the inconvenient infatuation one of the killers develops for a woman who should have wound up in the smokehouse to the climactic chainsaw fencing match between a cop and a cannibal, and unlike The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, it did it in a witty and amusing manner. The closest this movie ever gets to funny is during the first few minutes of Paul’s visit to the radio station, but Bill Moseley’s shtick wears thin fast, and he’s already crossed over to the Annoying Zone by the end of the scene. Otherwise, it’s just, “Ha, ha— look at the silly rednecks!” or worse yet, something akin to a homicidal Jerry Lewis routine. Look to the scenes set in the Sawyers’ lair for an example of the latter. For what feels like hours, all that happens is the Sawyers run around in circles, waving their arms and hollering incoherent abuse at each other while Stretch sits tied up in a chair and shrieks, “Please, God, let me go!” over and over again. Even when Lefty finally shows up, there is no mercy for the audience, for Drayton and Paul continue their hollering and arm-waving over top of the racket generated by the dueling saws. When will Hollywood learn that loud is not the same thing as funny? And don’t even get me started about that “Sawyer” business…

But there’s an aspect to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 that’s even worse than the poor copying of Motel Hell, and if the latter problem seems to be mostly the fault of the screenwriter, then this other must surely be pinned on Tobe Hooper. Entirely too much of what goes on at the Sawyer place is duplicated from what Sally Hardesty experienced in the preceding film. There’s dinner with grandpa (with Ken Evert taking over from John Dugan), there’s a head-whacking scene… even Paul’s pursuit of Stretch as she tries to get away at the end plays out like a simple restatement of Sally’s corresponding flight from the hitchhiker. The real trouble with all this (and here’s where Hooper comes in) is that every bit of it was much too grisly the first time around to be even remotely funny, and even though we’re supposed to be laughing now, Hooper’s camera seems to take the same basic attitude as before toward the events it records. We can see from all the dancing and hooting that it’s now meant merely as a harmless joke, but Hooper is much too serious a filmmaker to pull such levity off, and try as he might not to, he keeps reminding us that what we’re really doing is watching a woman being tortured. This disconnect between intent and execution is strongest in the one scene this movie has that wasn’t lifted from somewhere else, the one in which Leatherface flays L.G. and then dresses the captive Stretch up in his skin. Bill Johnson’s Leatherface (as befits the new “Bubba Sawyer” moniker) is a pathetic, bumbling buffoon, light-years removed from Gunnar Hansen’s honestly frightening interpretation of the character, but no amount of clowning on his part can disguise the fact that this is a vile, ghastly scene being played out. Hooper’s instinct as a filmmaker is to slap us in the face with the horror of the situation, and he is powerless to rein that instinct in. The result— here especially, but throughout the entire film as well— is that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 fails to work at any level. It certainly isn’t funny, but its insistence upon striving for forced mirth even in the face of the most grueling sadism short-circuits any real sense of horror that might have been developed instead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact