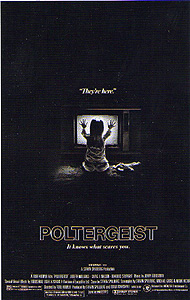

Poltergeist (1982) ***

Poltergeist (1982) ***

Of all the potential collaborations between filmmakers that might produce a big-budget, mainstream horror film, I can think of few that sound less likely than a team-up between Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper. Even looking at Spielberg as the man behind Duel and Jaws (as opposed to E.T.: The Extraterrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind), it just doesn’t seem natural to have him working side by side with the director of Eaten Alive and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And yet exactly that pairing is responsible for Poltergeist.

Understandably, virtually all reports have it that the partnership between the two men was often an unhappy one. The credits may list Hooper as the sole director, while billing Spielberg as producer instead, but the more famous filmmaker obviously took an extremely hands-on approach to the job, by some accounts even to the extent of dictating to Hooper everything except the bare mechanics of where to put the cameras and when to change the shot. Indeed, there is some indication that Spielberg even went back and re-shot a few scenes which Hooper did not direct to his liking. If even half of the stories are true, it’s no wonder Hooper chaffed under Spielberg’s leadership, nor is it at all surprising that the completed film gives off some strange vibes of internal discord. For while it is unquestionably Spielberg’s style that dominates in Poltergeist, there are a few hard sucker-punches that feel much more like Hooper’s stock in trade, together with a handful of gore effects that would have to be considered startlingly explicit by Spielberg’s usual standards.

Steven Freeling (Craig T. Nelson, from The Return of Count Yorga and the made-for-TV Creature) is a Southern California real estate agent in the employ of a developer named Teague (James Karen, of Hooper’s Invaders from Mars remake and The Return of the Living Dead). Freeling is Teague’s most valued worker, responsible for some 40% of the sales in his company’s snidely-named Cuesta Verde development (the name means “Costs Green”— for once, we see a Movie Spanish toponym whose creators clearly knew what they were doing), and consequently, the firm permits Freeling and his family to live in one of their expensive McMansions on what amounts to a lend-lease basis. That family consists of Steven’s wife, Diane (Jobeth Williams), and three children: sixteen-year-old Dana (The Haunting of Harrington House’s Dominique Dunne), eight-year-old Robbie (Don’t Go to Sleep’s Oliver Robbins), and five-year-old Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke). Carol Anne is the first of the kids we meet. She and her parents had fallen asleep while watching TV together, but the girl is awakened by the sudden roar of static when the local television station terminates broadcasting for the day. (Now how’s that for an example of how much the world has changed even since the early 1980’s? It occurs to me that many of my younger readers may have no firsthand memories of a time when turning on the television at 3:00 in the morning got you nothing but fifteen channels’ worth of dead air.) Carol Anne gets up to turn off the TV, but when she gets close enough to touch the set, something strange happens— she begins speaking, as if she were carrying on a conversation with a voice that only she can hear. Her talking wakes the adult Freelings, and gives them a bit of a scare before Steven turns off the TV and his daughter snaps out of it.

Carol Anne spends the next couple of days watching as much static on TV as she can find, presumably in an effort to get back into contact with whatever she believes she was talking to on the open channel. Then, on a night when she and Robbie have joined their parents in bed to find comfort in the face of a frighteningly intense thunderstorm and the even more frightening effect of the lightning strobing on the bark of the gnarled old tree outside their bedroom window, Carol Anne again hears the call of mysterious voices from the television. This time, when she leaves the bed to squat in front of the snowy screen, a spectral hand reaches out from the glass to touch her, after which there is a strange, electrical-looking discharge and an earthquake-like shaking of the house. The tremors jar the rest of the family awake, and when the vibrations subside, Carol Anne announces, “They’re here.”

The next morning, Diane discovers that something is causing the chairs around the kitchen table to move all by themselves. By the time Steven comes home from work, she has determined that there is a predictable pattern to the movements, and that any object— even a person— may be dragged across the room by an unseen force if it is placed in a certain position on the kitchen floor. The Freelings’ trip next door to ask the Tuthills (Michael McManus, from Deadly Eyes, and Virginia Kiser, of Space Raiders and Dreamscape) if they have experienced anything similar gets them nothing but some suspicious stares and an uncomfortable silence. Conditions rapidly escalate from weird to terrifying; there is another thunderstorm that evening, and in the midst of it, the tree in the backyard reaches in through the children’s window, seizes Robbie, and begins to eat him. Steven only narrowly rescues his son before a tornado sweeps down the street and uproots the animate tree, and in all the confusion, there is nobody in the house to notice when the kids’ closet door swings open of its own accord, and some kind of transdimensional vortex opens up to suck Carol Anne right out of her bed. All the other Freelings know for certain when they go back inside to check on her is that Carol Anne is neither in the bedroom, nor apparently anywhere else in the house. At first, Steven and Diane fear that their younger daughter may have run outside and fallen into the freshly dug pit (now half-filled with muddy water) that was to become the Freelings’ new swimming pool, but then Robbie hears his sister’s voice calling from the television in his parents’ room, just barely audible over the white noise of the after-hours static. From that moment forward, the younger children’s bedroom becomes a locus of constant high-level poltergeist activity, to the extent that it is unsafe even to set foot over the threshold.

In the aftermath of Carol Anne’s disappearance, Robbie gets packed off to his grandmother’s place, and Dana begins spending most of her time over at friends’ houses. Steven tells Teague that he’s come down with an incapacitating flu, and Diane passes the same tale along to Carol Anne’s kindergarten teacher to explain the girl’s continued absence from school. With their cover story securely in place, Steven and Diane begin shopping for parapsychologists. Eventually, they find a woman named Dr. Lesh (Chiller’s Beatrice Straight), who agrees to investigate the Freeling house together with her assistants, Marty (Martin Cassella) and Ryan (Richard Lawson, from Scream, Blacula, Scream and Sugar Hill). To say that the ghost hunters are unprepared for what they find would be a considerable understatement— imagine the crew of the Mystery Machine paying a visit to the Belasco House, and you’ll have some idea just how far out of their depth Lesh and her colleagues really are. In addition to what Lesh calls the “area of bilocation” (that is, the dimensional cul-de-sac where Carol Anne is currently trapped) and the violent poltergeist disturbance in the bedroom, the investigators encounter a procession of ghosts parading down the stairs to the living room, animate food, and a harrowing incident of sensory hijacking that scares Marty clear out of the ghost-hunting business. Eventually, Lesh comes to understand that she’s no match for whatever has taken up residence in the Freeling house, and she departs for a few days to call for backup.

That backup arrives in the form of a strange little psychic lady named Tangina Barrons (Zelda Rubinstein), apparently an acquaintance of Lesh’s from some prior undertaking. After looking over the Freeling house, Tangina concludes that Lesh’s “area of bilocation” is in fact a portal to the limbo between this world and the next, and that some powerful, malevolent spirit has abducted Carol Anne in an effort to gain dominion over the souls of the recently dead who have not yet completed the transition to the afterlife. After discovering that objects thrown into the closet where Carol Anne disappeared will rematerialize just below the ceiling in the living room, the psychic and the parapsychologists concoct a somewhat desperate scheme to free the little girl and break the power of the evil spirit: Steven and Ryan will hold the ends of a rope passing through the area of bilocation, said rope to be wrapped around Diane’s waist. Diane will then cross over into limbo and rescue her daughter, while Tangina shepherds the wandering souls into the light which marks the entryway to the next world. The plan, despite a few close calls, is a resounding success, and Tangina pronounces the Freeling house “clean.” Unfortunately for the Freelings, however, Tangina appears not to have nearly so accurate an understanding of the situation surrounding their house as she believes…

It’s a remarkably uneven movie, and it is nowhere near as effective as I remember it being, but Poltergeist is still one of the stronger haunted house films of the 1980’s. What I appreciate most about it is that the nature of the Freelings’ paranormal persecution is never conclusively explained. Several characters have their pet theories— Tangina Barrons has her stereotypical New Age mysticism, Dr. Lesh talks about resentful souls who quite simply refuse to accept their own deaths, Steven eventually concludes that the attacks have something to do with the tenants of the cemetery that once stood on the land that became Cuesta Verde— but all of these hypotheses have troubling blind spots, and are unable to account for at least one major aspect of the haunting. That reticence on the filmmakers’ parts permits Poltergeist to play as broad a field of supernatural manifestations as possible without suffering from the sort of logical inconsistencies that helped scupper The Amityville Horror. After all, you can’t really complain about a story not following its own rules when it refuses to give you a solid basis for determining what those rules might be in the first place! The filmmakers’ decision to cast the movie with actors of considerable ability but little repute— several of them existing at a fair remove from the usual Hollywood beauty standards— was another wise move, counterbalancing an unbelievable situation with essentially believable people.

Where Poltergeist suffers is in those areas where Spielberg’s instincts and Hooper’s were most strongly at variance. To all appearances, Spielberg was looking to make a family-friendly horror film. The centrality of the two child characters, the emphasis on supernatural manifestations that play directly to childhood fears (like the creepy old tree and the clown doll that comes to life and attacks Robbie from under his bed), the remarkable fact that not a single character suffers any permanent physical harm over the course of the film— all these things suggest that Spielberg was trying to do for horror what his contemporary E.T.: The Extraterrestrial sought to do for sci-fi. It hardly needs to be said that Tobe Hooper was not a conspicuously suitable partner for such a project. The grisly hallucination which confronts Marty in the bathroom mirror is more his speed, as is the skeletal monstrosity that appears to be the preferred visible form of the thing haunting the Freeling house. Neither man seems to have been nimble enough as a filmmaker to shift gears smoothly between the Spielberg moments and the Hooper ones, and the strain is clearly visible, especially in the climax, when the entity in the house rallies its energies after the setback of losing Carol Anne. I’m honestly not sure, however, whether the solution to Poltergeist’s problems would have been for Spielberg to allow Hooper a longer leash, or for him to cut Hooper loose altogether and trust himself to get back in touch with whatever inner darkness had powered Jaws.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact