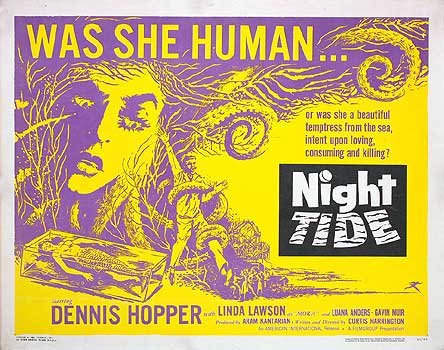

Night Tide (1961) **½

Night Tide (1961) **½

Here’s another one for the Val Lewton fans left cursing the brevity of his career as RKO’s unwilling scare specialist. Night Tide is, if anything, even more oblique than the genuine Lewton horror films of the 40’s, and harder to fit into any standard genre pigeonhole. Although its story can be simplistically glossed over as “Cat People with a mermaid,” Night Tide also incorporates some innovations from the then-burgeoning psycho-horror subgenre, and intensifies the focus on ill-advised romance with a doomed and possibly dangerous woman to positively noirish extremes.

Johnny Drake (Dennis Hopper, from The Trip and Firestarter 2: Rekindled) joined the navy about a year ago in the hope of seeing the world, but all he’s seen so far is greater Los Angeles. On liberty one Saturday night, he finds himself in a Santa Monica jazz club called the Blue Cove, where he spots a startlingly beautiful girl (Linda Lawson, of Let’s Kill Uncle and Mrs. Stone’s Thing) sitting alone on the other side of the room. Pleading the invisibility of the band from his previous vantage point, Johnny gets the girl’s permission to join her at her table, and tentatively, squarely, ineptly begins putting the moves on her. Her name is Mora, which might be a bad sign. This isn’t a vampire movie, of course, but Johnny might want to think twice about pursuing a relationship with someone whose name means “vampire” in Czech just the same. At first, Mora stonewalls his attempts at small talk with all the practiced efficiency of a pretty girl who fends off the advances of a dozen losers a day, but then an opening presents itself from a completely unexpected quarter. A severe-looking, black-clad woman (Marjorie Cameron) accosts Mora at the table with the mien of a disapproving nanny, and says something to her in a foreign language before marching out the way she came. Visibly disturbed by the intrusion, Mora gets up at once and flees the Blue Cove— unwittingly giving Johnny an opportunity to play protector. Catching up to her around the corner from the club, he offers to walk her home, and she accepts with a curious mixture of relief and reluctance. The young sailor pours on his best approximation of charm along the way, and succeeds well enough that Mora agrees to have him over for breakfast tomorrow morning.

The girl’s living arrangements are cutely eccentric. She rents an apartment right on the Santa Monica amusement pier, directly above the merry-go-round. Johnny has occasion to chat with her landlord (Tom Dillon, from the late Universal Sherlock Holmes films, Dressed to Kill and Pursuit to Algiers) while the latter man is opening up the carousel pavilion, and proves himself to be not so naïve as he looks. The sailor notices the look of disquiet that crosses the old man’s face when he mentions his date with Mora, and has the good sense to misrepresent himself as an acquaintance of long standing. After all, it’s 1961— a girl might get evicted if her landlord catches her making breakfast for guys she’s just met! The location of Mora’s home turns out not to be the only odd thing about her daily life, either. She decorates her flat with stuff that washes up on the beach, she’s an expert angler, and she can catch a seagull with her bare hands if one comes close enough to her. Oh— and she’s also a professional mermaid.

Wait— what? Well, her adoptive father, a retired sea captain named Sam Murdock (Gavin Muir, from Island of Lost Women and The Son of Dr. Jekyll), leases his own kiosk on the pier, where Mora exhibits herself as “the only live mermaid in captivity.” Basically, she sits around all day combing her hair in a tank built to look like it’s full of water, wearing a phony fish tail over her legs. Johnny’s first conversation with Murdock is even more peculiar than his earlier talk with Carousel Guy. The captain says he “found” Mora on the isle of Mykonos, and indicates that there’s something he needs to discuss with Johnny in greater privacy than there is to be had on the pier on a Sunday afternoon. But enigmas or no enigmas, Johnny really likes Mora, and as they see more of each other over the ensuing days, she grows to like him a lot, too.

One of the mysteries surrounding Mora is, if not exactly cleared up, then at least partly elucidated the next time Johnny comes by the merry-go-round. This time, the owner’s granddaughter, Ellen (Luana Anders, of The Manipulator and The Killing Kind), is out and about, and they’ve got guests of their own. The first of those is Madame Romanovich (Marjorie Eaton, from The Zombies of Mora Tau and Monstrosity), the pier’s fortune teller. The other, curiously, is a police detective (H. E. West). Lieutenant Henderson is investigating the drowning deaths of Mora’s two previous boyfriends, and although he has no evidence that would support an arrest, everyone just knows that she killed them. And even if she didn’t, having two boyfriends in a row die on her must mean that she’s bad luck somehow. Johnny is still trying to process that revelation when the phone rings, and Carousel Guy announces that it’s for him. The line goes dead as soon as Johnny greets the unknown caller, but he sees the black-clad woman from the Blue Cove zipping away from a phone booth on the nearest street corner a second later.

Johnny gives chase, and soon finds himself wending his way ever deeper into Venice. Eventually he loses sight of the woman, but discovers that she has led him straight to the home of Captain Murdock. There’s no way that’s a coincidence, right? This leads to further elucidation, for while Sam drinks himself under his own coffee table, he warns Johnny that Mora is much more than she seems. She may not look like it when she isn’t dressed up for work, but Murdock’s foster daughter is a Siren, one of the mer-people known to the ancient Greeks. (Nevermind that the Greek Sirens were half-bird, not half fish.) Her kind want her back, and each full moon, when the tide is at its strongest, they come close to getting her. That’s when her boyfriends tend to turn up dead. So really, Johnny is doing himself no favors with this romance of his. And if he’ll take a look at the calendar, he’ll see that the full moon is only a few days away.

To Johnny’s considerable surprise and dismay, Mora’s reaction when he tells her about talking with Murdock basically boils down to, “Oh, I’m sorry. I’ve been meaning to say something about that myself, but I just couldn’t work up the nerve.” And let’s be clear that she means confessing to being a Siren, not confessing that her foster dad is out of his fucking mind. Johnny still doesn’t buy it, any more than he buys that Mora drowned his two predecessors, but obviously the situation gets a little stickier if she does.

Johnny feels so far out of his depth at this point that he seeks advice from Ellen and Madame Romanovich. One may be hostile to Mora and the other a crackpot, but Ellen’s hard-headed practicality and Madame Romanovich’s maternal wisdom would each really come in handy right about now, and both women already know at least a little about what’s going on. Between the fortune teller’s tarot reading and Ellen’s rather surprising pep talk, Johnny comes away thinking of Mora’s delusion as a challenge to be worked through rather than a cue to put as many miles between him and his new girlfriend as possible. But then the full moon arrives, bringing with it a danger equivalent to, if significantly different from, the one everyone’s been warning him about since he first took up with the troubled girl.

Curtis Harrington ought to be better remembered than he is. In the 80’s, toward the end of his career, he directed Sylvia Kristel in Mata Hari, pretty much the last gasp of the vogue for glossy, big-budget soft porn that kicked off a decade before with Emmanuelle. In the 70’s, he flogged the corpse of 60’s psycho-horror with mixed results— ranging from the mediocre How Awful About Allan to the unsettlingly vicious The Killing Kind— then switched to television, where he directed Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell and The Dead Don’t Die among others. Before that, he worked for Roger Corman, turning Planet of Storms into Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet and A Dream Comes True into Queen of Blood. And along the way, he was responsible for the memorably bizarre Games and Ruby. Night Tide was his first feature film, coming after a string of avant-garde shorts and a gig as Kenneth Anger’s cinematographer.

Among those who do remember Harrington, it’s fashionable to think of Night Tide as the pinnacle from which he spent his whole career steadily declining, but that’s much too shallow an interpretation. In some ways, Harrington stuck with the pattern established by Night Tide right to the end, since his best work and his crummiest alike begins in pastiche (or, in the case of the Corman cut-and-pastes, literally in somebody else’s film), then attempts to push beyond it. The difference between a good Curtis Harrington movie and a bad one is whether or not the push succeeds. In Night Tide, it succeeds only imperfectly. Like most attempts to ape the Val Lewton style, this movie doesn’t quite stick the landing because it gets the ambiguity out of balance. In particular, it borrows the worst possible idea from the Psycho school, ending with dry and static scene in which some talking head reduces the whole movie to five minutes of blah-blah-blah. Night Tide goes beyond “Dr. Boring Explains It All,” though, encroaching on the salted earth of a 1930’s “rational explanation” ending. True, Harrington leaves one detail that tantalizingly doesn’t fit— the mysterious woman in black— but it fails to fit so completely as to shrink to the status of a mutant red herring. Not fitting the tidy scheme laid out in the finale stands revealed as the woman’s sole purpose, since that tidy scheme is too convincing even with her around to permit any alternate reading of the story.

Up until that concluding fumble, however, Night Tide is the only Lewton copy I’ve seen to rival the peak effectiveness of the real thing, which is all the more impressive for a film that starts out as so slavish a rip-off of Cat People (right down to the “Moia sestra” moment!). The key is Johnny Drake and Dennis Hopper’s performance in the role. Cat People was radical enough in its day for making its sexy, European vamp a virginal shut-in, and its unthreatening, all-American career woman a homewrecker, but Night Tide goes further still by presenting the man as a sheltered, unworldly naif. Harrington also resists (again, until that disastrous final scene) the temptation to set up a triangle among Johnny, Mora, and Ellen. What we have here is just a wide-eyed boy in love with a girl who everyone tells him is bad news, and his very determination to do right by her almost becomes his undoing. Johnny’s commitment to seeing the best in Mora creates a strong and satisfying parallel between the up-front romance plot and the mystery of murders and mermaids lurking in the background. Sam Murdock becomes both a disapproving father figure and something much more sinister. The possibility that Mora is a killer Siren acquires metaphorical resonance as a symbol for Johnny’s simultaneous excitement and unease at landing a partner more sexually experienced than himself. Ellen’s attitude toward Mora works in one context as destructive mean-girl bitchiness, and in the other as the disregarded voice of a Crazy Ralph-like harbinger of evil. And because the two plots do run so perfectly parallel to each other, Harrington is able to keep us constantly off balance with regard to which one is advancing at any given moment. It’s an elegant construction, and all the more remarkable when you consider that Harrington had never made a feature film before. So while I can’t quite consider Night Tide to be the out-of-nowhere masterpiece of its reputation, it does come awfully close to that level before its engines sputter out and it falls to earth.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact