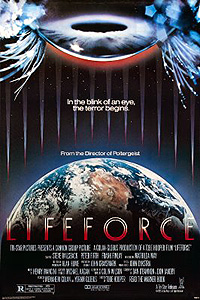

Lifeforce (1985) ***

Lifeforce (1985) ***

Far be it from me to dispute the oft-made assertion that Tobe Hooper has never really lived up to the promise of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Any “outlaw” horror director whose second-best film was produced originally for broadcast television unquestionably has some serious career troubles. One facet of the common assessment of Hooper’s career which I will dispute quite vehemently, however, is the claim that Lifeforce is among the foremost examples of his chronic inability to get it together in the years since his auspicious debut. Though it is a chaotic and somewhat muddled picture, and though it performed quite miserably at the box office (taking in less than half of its reported cost), Lifeforce is also Hooper’s most ambitious movie by a comfortable margin, and it is the closest thing we have to a theatrically released Quatermass film for the 1980’s.

One point of commonality between this movie and the Quatermass trilogy becomes immediately obvious in the very first scene— Lifeforce, too, apparently takes place in a parallel universe where Great Britain has managed to maintain a cutting-edge space program. The space shuttle HMS Churchill, operating with a combined British-American crew under the command of US Air Force Colonel Tom Carlsen (Steve Railsback, from Blue Monkey and Disturbing Behavior), is on a mission to intercept Haley’s Comet when the ship’s radar officer detects a strange object in the gas cloud surrounding the comet’s head. It’s a needle-shaped thing with a bulb at one end and a sort of furled cone structure at the other, and it doesn’t appear to be made of the same substance as the comet. Furthermore, the object’s symmetry strongly suggests that it is of artificial origin— an extraterrestrial spacecraft, perhaps? If so, its builders take their space travel a hell of a lot more seriously than we humans do, for the object is roughly 150 miles long and two miles across at its widest point. Stunned by the potential implications of the discovery, Carlsen orders the Churchill in close enough for him and about half of the shuttle’s crew to go over and have a look; they won’t be able to tell mission control what they’re up to, however, because electromagnetic interference caused by the comet’s interaction with the solar wind has cut off all communications.

The thing in the comet is an alien spacecraft, alright. It’s also a ghost ship, and once the astronauts find a way inside, they are confronted with thousands of vacuum-desiccated, bat-like carcasses adrift within the massive hull. But while the crew may be dead, the ship itself apparently is not— soon after Carlsen and his team have gone aboard, the conical structure at the stern of the ship opens up like a vast umbrella. The away team have something even more pressing on their minds, however, for by that time, they’ve found the chamber in which three apparent humans— one woman (Mathilda May) and two men (Christopher Jagger and Bill Malin)— repose in what might equally well be death or suspended animation within sealed capsules made of no known material. Carlsen orders all three of the “humans” brought back to the Churchill, together with one of the freeze-dried bat creatures.

Thirty days later, mission control still hasn’t heard a peep out of the Churchill. When the ship finally falls back into orbit around the Earth, its position indicates that its course probably hasn’t been updated since leaving Haley’s Comet, and it’s impossible to escape the feeling that something has gone seriously wrong. NASA launches the shuttle Columbia on an intercept course, and the rescue team from the American ship finds that it’s far too late for them to do much of anything. The Churchill’s interior has been gutted by fire, and it looks like the entire crew was caught in the blaze— although the condition of the bodies makes it impossible to say for certain. The one slim hope for seeing any of the Churchill crew again lies in the empty launching bay for the shuttle’s escape pod. But the cargo bay still contains the three capsules from the alien ship, and the human-looking bodies inside them are completely undamaged despite clear signs that the conflagration did indeed reach the hold. All the data tapes from the shuttle’s mission recorders were melted by the fire, and so Dr. Bukovsky (Michael Gothard, of Scream and Scream Again and The Devils), the scientist charged with analyzing the results of the mission to Haley’s Comet, has a real mystery on his hands. What were three naked human bodies doing in the vicinity of the comet? What are the strange and apparently invulnerable machines in which they are enclosed? And what in God’s name happened to the Churchill on the trip home?

Bukovsky soon has lots of company on the project. Home Secretary Sir Percy Hesseltine (Aubrey Morris, of Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb and Night Caller from Outer Space) takes a personal interest in the matter, and he sees to it that Bukovsky gets the best help available. Dr. Hans Fallada (Frank Finlay, from Twisted Nerve and Cthulu Mansion), a biochemist specializing in thanatology, is brought in to determine whether the bodies from space are living or dead, and huge amounts of time and money are poured into unlocking the secrets of their indestructible coffins. Fallada can find no trace of vital signs in any of the bodies, but he is quick to point out how little that means, considering that there’s an excellent chance that the bodies aren’t actually human at all. The scientists working on the coffins come to no firmer conclusions, having been brought up short by startling evidence that the devices may not even be physical objects in the usual sense. Meanwhile, Colonel Colin Caine of the SAS (Mighty Joe Young’s Peter Firth, who dubbed Miles O’Keefe’s voice for Sword of the Valiant) arrives on the scene to manage the national security aspects of the situation.

That’s where the matter stands until the night when the space coffins open up of their own accord, and the female “body” returns to life. One of Bukovsky’s colleagues has just begun another examination of her at the moment of her awakening, and Bukovsky himself watches over the laboratory’s closed-circuit television as she first seduces the speechless man and then begins draining away his life-energy with a kiss. Bukovsky runs down to the lab, arriving just as the reanimated woman finishes with the other man. The scientist will later explain to Colonel Caine that the overwhelming “feminine presence” of the woman from space paralyzed him with a debilitating combination of lust and terror, leaving him powerless to impede her escape. The laboratory guards fare even worse, one of them getting his life sucked out when he attempts to restrain her.

Two hours later, an even more alarming complication arises. The dead guard interrupts his own autopsy by returning to life and subjecting the medical examiner to the soul-sucking treatment; subsequent events prove conclusively that anyone drained of life-energy by what Fallada now takes to calling the “vampires” will revive after about two hours with an insatiable lifeforce-thirst of their own. And while the resurrected victims of the vampires prove to be no more difficult to kill than a normal human, the same is by no means true of the original three. When the space woman’s male consorts awaken soon thereafter, they demonstrate an imperviousness to anything short of high explosives, combined with a distressing ability to abandon a ruined body and commandeer any other that happens to be handy— evidently not even blowing them up will destroy the space vampires permanently.

There is one small piece of good news, though. Not long after Caine loses track of all three vampires, the Churchill’s escape pod turns up, with the still-living Colonel Carlsen inside it. What’s more, Carlsen turns out to have a psychic link with the vampire woman as a consequence of something she did to him out in the interplanetary void. Caine thus has a way of tracking the vampire’s movements even after she ditches her original body and possesses a psychiatric nurse named Ellen Donaldson (Nancy Paul, of Sheena and Love Potion), who works for Dr. Armstrong (Patrick Stewart, from Dune and Excalibur) at the Thorlstone Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Two new developments are about to raise the stakes enormously, however. First, the alien ship appears in Earth’s neighborhood, assuming a geosynchronous orbit directly above London. Secondly, the three vampires on Earth have been busier than anybody realizes, infecting a sufficiently large fraction of the city’s population to trigger a mass outbreak of vampirism just in time for their vessel’s arrival. By the time Carlsen, Caine, Fallada, and the others have assembled enough pieces of the puzzle to have a chance of stopping the invasion, the situation in London has become so apocalyptically bad that the city is under martial law, with representatives of NATO giving serious consideration to the possibility of “thermonuclear quarantine.”

Truth be told, Lifeforce doesn’t so much resemble a Quatermass movie as it resembles all three of them in rapid succession, spiced up with a little bit of both Alien and The Last Man on Earth. The spacefaring locked-room mystery that opens the Earthbound section of the film recalls The Creeping Unknown, the ability of the vampires both to possess and to convert humans leads to a number of parallels with Enemy from Space, and the havoc-intensive third act is straight out of Five Million Years to Earth. The prologue aboard the alien ghost ship, meanwhile, is openly derived from Alien (screenwriter Dan O’Bannon even reuses some of his Alien dialogue), and the singleminded frenzy with which the newly risen vampires seek their initial sustenance provides an excuse for an extended detour through zombie-movie country once the vampire invasion shifts into high gear. All those rapid mood-swings do make the movie just a little taxing to follow, and I can understand why so many people simply give up and declare Lifeforce an incoherent mess. But Lifeforce isn’t incoherent— it simply tackles a lot of different styles and subgenres in serial fashion, and expects the audience to keep up. Each phase of the movie, from the discovery of the seemingly derelict spaceship to the onset of the London vampire plague, is perfectly coherent in and of itself (with the exception, that is, of the Thurlstone Hospital segment and the very end, both of which really are grade-A head-scratchers), and each one flows more or less logically into the next. Only when you attempt to draw a direct line between the Churchill’s visit to Haley’s Comet and the dizzying chaos that eventually engulfs London does the mind blow a fuse on the question, “Wait— how the fuck did we get here?!?!” It’s a mistake to try drawing that line in the first place, however, because the circuitousness of Lifeforce’s story is itself a large part of the point. You don’t take a rambling country road when you’re looking for the most efficient route from point A to point B— for that you get on the expressway. Similarly, Lifeforce is a movie in which the journey is more important than the destination. And so far as I’m concerned, any journey involving an interstellar ghost ship, vampires from space, a doppelganger invasion, a sci-fi murder mystery, a zombie apocalypse, and enough naked Mathilda May to wallpaper a peepshow booth is one well worth taking.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact