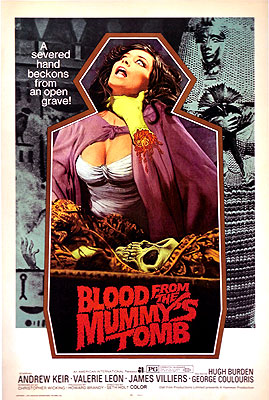

Blood from the Mummyís Tomb (1971) **Ĺ

Blood from the Mummyís Tomb (1971) **Ĺ

Iíve often remarked that 1971 was an extraordinarily good year for Hammer Film Productions, creatively if perhaps not financially. To some extent, that applies even to movies that were not themselves extraordinarily good. Even the weakest 1971 Hammer products took big risks and tried new things, like when Creatures the World Forgot made what might have been the worldís first good-faith attempt at a paleontologically plausible caveman movie (demonstrating to its detriment one possible reason why it hadnít been tried before). Blood from the Mummyís Tomb, adapted from Bram Stokerís 1903 sowís ear The Jewel of Seven Stars, similarly falls well short of silk purse status, but it was still the most interesting and original English-language mummy film since at least Pharaohís Curse.

The most immediately obvious thing that Blood from the Mummyís Tomb does differently is that its mummy is female, unwrapped (shit, sheís barely dressed), and incandescently hot. However, she also looks exactly like protagonist Margaret Fuchs (Valerie Leon, from Queen Kong and The Love Factor), so plainly weíre still sticking with the erroneous old notion that the ancient Egyptians not only believed in reincarnation, but also understood the concept the same way as the turn of the last centuryís Spiritualist movement. We open with Margaret dreaming of the night when her ancient doppelganger, the priestess Tera, was executed by her male colleagues for witchcraft, blasphemy, and all the rest of the usual bullshit. Naturally, the real story was that Tera had discovered cosmic secrets that made her a threat to the power of the religious establishment. Either way, the priests poisoned Tera and entombed her in a hidden valley. They also chopped off her right handó which symbolized to them her supernatural poweró and threw it to the jackals. The fact that the hand killed those jackals ought perhaps to have come as a warning to the priests, but the lag time between the animalsí deaths and the menís was so short that Iím not sure a hint in advance would have done the latter any good. No sooner did the priests exit Teraís tomb than they were caught in a sudden sandstorm, and their throats torn out by some invisible force suggesting an astral projection of that killer hand.

Now this next part isnít revealed until a flashback in the second act, but Iím going to tell you about it up front for the sake of sense and clarity. Margaretís father, Julian (Andrew Keir, of Dragonworld and Five Million Years to Earth), is an Egyptologist, and some 20 years ago, he and four other researchers found and excavated Teraís tomb. None of them have been quite the same since, although itís difficult to say exactly why. To be sure, it was unnerving as hell when Fuchs and his colleagues opened up Teraís sarcophagus, and found her body so uncannily preserved that the stump of her severed hand was still bleeding, but it isnít as if anything happened to them down there. Nevertheless, Berrigan (George Coulouris, from The Tempter and Itís Not the Size that Counts) is confined to an insane asylum now, keeping a perpetual paranoid vigil over the basalt cobra that became his souvenir of the venture. Helen Dickerson (Rosalie Crutchley, of The Haunting and The Gamma People) gave up archaeology altogether, and became a professional fortune-teller. Corbeck (James Villiers, from Repulsion and These Are the Damned) descended into megalomania, coveting the forbidden knowledge that Tera supposedly possessed; maybe that higher ambition explains why heís the only member of the team who didnít abscond with any of the mummy girlís grave goods. Geoffrey Dandridge (Hugh Burden, of Ghost Ship and The House in Nightmare Park) seems to have done alright, relatively speaking. If nothing else, heís still working, teaching, and publishing in his old field. But since heís also made a point of severing all contact with his fellow raiders of Teraís tomb, it may be that he rates his coping ability a good deal lower than might an outside observer. And Julian? Heís arguably taken the obsession with Tera the furthest of all, since he, unbeknownst to daughter, servants, friends, or anyone, has converted his basement into an exact replica of her tombó complete with the long-dead priestessís inexplicably imperishable corpse.

Whatever unnatural machinery has been idling ever since the opening of Teraís grave lurches into motion on Margaretís birthday, when her father gives her a ring that once belonged to Teraó a red stone the size of a thumbprint, engraved with the image of the Big Dipper. (I can only assume that the hieroglyphic texts revealing the constellation Orionís special place in Egyptian astrology had not yet been translated when Bram Stoker was writing the original version of this tale. Knowing what we do today, a Jewel of Nine Stars would be more apt.) Margaretís grad-student boyfriend, Tod (Mark Edwards, from Terror in the Wax Museum and Horror on Snape Island), innocently suggests that they take the ring to his boss for identification, not realizing that Fuchs doesnít want his daughter (or anyone else, really) to know the baubleís provenance. Tod turns out to work for Professor Dandridge, who requires every bit of his sharply honed English reserve to stave off an attack of the screaming Mimis when he sees Margaret with the artifact on her finger. The next thing anyone knows, Corbeck is spying on the Fuchses from the empty house across the street, Margaret is developing deadly psychic powers that donít seem to be quite under her control, and one by one the violators of Teraís tomb are coming under supernatural attack. Corbeck claims to know what itís all about. He believes that Tera is attempting to reincarnate herself through Margaretís bodyó maybe even that Tera orchestrated Margaretís birth from the nameless limbo in which she dwells precisely in order to create such a suitable vessel. He urges Margaret to submit to her destiny, entreating her to imagine the knowledge and power that will be hers once her consciousness merges with that of the mummy. Her father, however, takes a rather different view. He agrees with his colleague-turned-adversary on the subject of Teraís objectives, but he contends that a body can accommodate just one soul in the long run. For Tera to take up permanent residence within Margaret, Margaret herself must cease to exist. And besides, do we really want a shifty bastard like Corbeck acting as agent and advisor to a sorceress from the ruling class of a civilization that never got around to discovering human rights?

Director Seth Holt didnít live to complete Blood from the Mummyís Tomb. He had a fatal heart attack literally on the set, five weeks into the filmís six-week shooting schedule. Holt had shot most of the substantive scenes, fortunately, but heíd been saving the connective tissue between them for lastó and evidently he didnít leave much in the way of notes regarding what that connective tissue was supposed to be. Hammer boss Michael Carreras stepped in to finish the project, but seems to have had a rather lax attitude about what it would take to make sense of Holtís footage. So if you get the feeling that there ought to be more to this movie explaining how it gets from all the heres to all the theres, youíre quite right. Still, it wasnít totally unreasonable for Carreras to imagine that Blood from the Mummyís Tomb could get away with skimping on that sort of thing. After all, eliminating it altogether had done wonders for The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (although your guess as to whether Carreras ever actually saw that powerfully opaque picture is as good as mine). Alas, however, neither Holt nor Carreras was any Ricardo Freda, and Blood from the Mummyís Tomb just ended up feeling unfinished. Not enough dots are connected for it to be truly coherent, yet it mostly lacks at the same time the visual stylization that might have given it a compensating dreamlike quality. The cinematography and production design are the usual late-Hammer combination of deceptive lavishness and shabby practicality, with only the simulated exteriors in the Egyptian flashbacks conveying any hint of the Bava-esque artifice that the movie needed throughout if it was going to make this little sense. A bit more of that might have helped fend off the insistent questions of logistics and motivation for which Blood from the Mummyís Tomb has no answer more satisfying than ďa mummy did it.Ē

Even so, Blood from the Mummyís Tomb is worth a look just for straying so far off of the usual model for its subgenre, and itís worth a close look for Valerie Leonís commanding performance as Margaret. Although this movie looks on the surface like the usual male-focused Hammer film, with a heroine in need of rescue from some covetous supernatural evil, the situation proves, upon closer inspection, to be more complicated than that. Unlike any of Hammerís previous mummies, Tera never comes to life in the usual sense, and remains confined to her sarcophagus at all times. Sheís able to act only by triggering the magical booby traps built into her grave goods, and by influencing Margaret on a subconscious or unconscious level. That is, when Tera works against Margaret, she does it by working through her. Meanwhile, Julianís efforts to protect Margaret by keeping her in ignorance of her bond with the mummy realistically backfireó and backfire more seriously in direct proportion to the stakes of the drama unfolding around her. For her part, Margaret is driven by a commendable and completely sensible determination to discover whatís happening to her, but her father and his former colleagues have foolishly rigged it so that the only way she can get any answers is to cooperate with Corbeck on the material plane and with Tera herself on the astral one. It all means that Leon gets far more to do than the typical Hammer starlet, establishing her alongside Ingrid Pitt, Martine Beswick, and Angharad Rees as one of the rare Hammer girls to earn distinction for more than their physiques (although Leon is in about the 92nd percentile on that score, too). Alas, she also joined Pitt, Beswick, and Rees as a glaring example of the studioís chronic lack of interest in developing its most promising actresses. Incredibly, Blood from the Mummyís Tomb was her sole Hammer credit!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact